Why, and perhaps more significantly, when, did the theory develop that, around the beginning of the twentieth century, the Western world experienced a radical cultural shift? Was there a self-evident cataclysmic change, clearly observable to people living at the time? Or is this compartmentalization of history a retrospective invention? In Why Literary Periods Mattered (2013), Ted Underwood argues that the organization of English studies into discrete and distinct literary eras arose from a perceived need, around the middle of the twentieth century, to claim disciplinary autonomy by advancing a paradigm of rupture and contrast in marked contrast to the “rhetoric of transition and [gradualist] development” prevailing in social history. Yet, as Rudolph Glitz has shown in Writing the Victorians (2009), the period concept “Victorian” bears a distinctly “non-academic pedigree” (Glitz 14). To take one striking example, on January 23, 1901, The Globe – Canada’s national newspaper – carried the banner headline: “The Victorian Era Has Ended,” framed by the dates 1837–1901. Multiplied throughout the world, such images and pronouncements firmly embedded the idea of a Victorian period in the public mind. Modernism, too, emerged early as a period concept in popular culture. One of the first twentieth-century uses of the term cited in Modernism: Keywords (2014) occurs in a 1911 ad in Cosmopolitan magazine recommending a wedding present for the “model home”: Rubdry Towels, we are told, “are in particular favor with men” and should be owned by “Every family who takes pride in the bath-room” as “a sign of modernism and true refinement.”1 Harnessing the progressiveness of the new age to sell its products, the advertiser reinforces the myth of the Victorian/modernist divide.

After initial premonitions of a turn of the twentieth-century break, however, the subsequent history is far from simple. Although the notion of a divide eventually takes tenacious hold, continuities over the centuries and various micro-eras, such as periods of war, reveal the divide to be only one pattern among many. We can perhaps most easily grasp such complexity through visualization, and so I turn to big data graphs produced by the readily accessible Ngram Viewer, available from Google. The approach here is grounded in the history of language and is based on the supposition that the rising and falling fortunes of specific words, the vocabulary coming into and going out of fashion, are large-scale indicators of cultural change.

Ngram Viewer Graphs: A Big Data Approach

The Ngram Viewer constructs graphs that plot the relative frequency with which words appear, according to the year of publication, in the millions of digitized books and magazines in the Google Books corpus.2 Unlike a keywords approach, which tracks variant meanings, Ngram Viewer graphs tell us the relative frequency with which a word is appearing in print, indicating a word’s changing circulation over time (to compensate for increasing publication in chronological time, the graphs express word usage proportionally, as a percentage of all words used in each year). The vast database is instantly searchable for words and phrases, in numerous combinations, in different languages, and within adjustable time frames from 1500 to 2008. “Culturomics” – the associated field of study – uses the quantitative data about lexical developments to analyse changes and consistencies in cultural practices and concerns. Searching for periodizing terms through the large, heterogeneous mix of digitized Google Books, for example, can help us assess the extent to which the literary constructs of Victorian and modernist reflect observable trends in the cultural discourse as a whole.

Ngram searching, I’ve found, can be fascinating and addictive, given all the possibilities of words and their combinations to pursue; nonetheless, in analysing the results, we must keep several cautions in mind. Since the Ngram Viewer charts every instance of every word, regardless of how it is being used, it’s not easy to eliminate meanings you don’t want. When I found “Victorian period” occurring before 1837, for example, I discovered an earlier sense, pertaining to a lunar period in the Julian calendar named after the astronomer Victorius of Aquitaine. Second, the database as it currently exists is not 100 per cent reliable. Early OCR (optical character recognition) of digitized books was notably imperfect and mistakes in translating to readable text do occur. When searching through citations for highbrow, for example, I encountered the wonderful phrase “the sweat of highbrow.” Locating the source in The Farmer’s Magazine (1880), however, I discovered the words were actually “the sweat of his brow” (117). Publication dates can also be entered in error, particularly for early works. A collection of works by John Ruskin (1819–1900) was arbitrarily assigned the date 1800, since it was published during the nineteenth century but bore no date. Some problematic issues emerge in data entry, too: a collection of art catalogues spanning several decades was assigned a single date; each volume in a four-volume series of essays published over several years was given the date for volume one.3

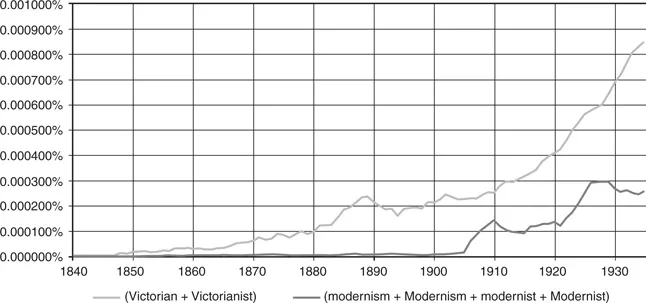

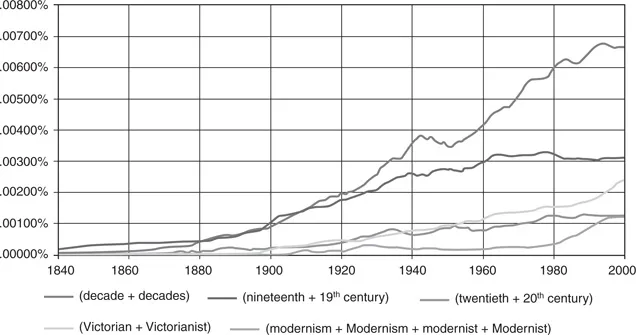

Given such limitations, can Ngram Viewer charts still be effectively used? Clearly the answer is not yet, if what we are seeking is fine-grained analysis. Nonetheless, if our time frame is long enough, and the number of books high enough, the Ngram Viewer will reveal informative, large-scale patterns, reliably indicating general trends and their pace of development over time. While the Oxford English Dictionary cites the first use of Victorian referring to the Queen’s reign as 1839, the Ngram Viewer shows that the adjective starts to become prominent only in the later years of Victoria’s life, maintains approximately the same frequency between 1886 and 1911, and embarks on significant growth around 1912.4 From this point, although Victorian(ist) occurs approximately ten times more frequently than modernism,5 both words experience a parallel rapid increase until the 1930s (Figure 1.1).6 Expanding the timescale to the present then causes a striking difference to appear (Figure 1.2). While the subsequent rise of Victorian(ist) slows to a very gradual pace, modernism(t)’s early growth in the 1920s pales in comparison with its rapid growth spurt beginning in the late 1970s, making modernism(ist) and Victorian(ist) relatively equal in frequency by the century’s end. What Figure 1.2 also depicts is the parallel but even greater growth of the terms nineteenth and twentieth century; a little surprisingly, the former term is used relatively infrequently during its own time, compared to the strong and steady rise of both terms in the twentieth century. Even stronger increases are evident for the words decade(s) and century, although the latter is omitted from Figure 1.2, since its much higher frequency would dwarf the other words in scale.

What observations are then prompted by these graphs? The first decade of the twentieth century is accompanied by a new or stronger interest in distinguishing the immediate past from the present, lending credence to Virginia Woolf’s only somewhat fanciful positing of significant change “on or about December 1910” (Woolf 1986–2011, vol. 3, 421). Subsequently, however, the slow and steady growth of Victorian(ist) throughout the century, with no one moment of determining impetus, indicates a subject of diffused, general interest, as opposed to the sudden and late proliferation of modernism(t), presumably reflecting the first consolidated academic efforts to formulate the meaning of modernism in the arts.7 The late twentieth century advent of modernist studies does seem to be responsible for entrenching notions of the divide. Yet the motivation may have been less to acquire cultural prestige, as Ted Underwood suspects, than to gain a newcomer’s toehold within the academy.8 After 1900, the accelerating use of the word century (in contrast to the steady, lesser use of era) and the virtual emergence and rapid establishment of the word decade suggest that one feature of the divide was a new interest in partitioning history into date-delimited periods. The word periodization itself – after negligible appearances in the early twentieth century, largely pertaining to the teaching of history in the elementary schools – begins to rise into significance in the mid-1930s, making its most rapid acceleration between 1950 and 2000. The twentieth century looks thus to be responsible not only for constructs of Victorian and modernist, but for periodization itself.9

That such periodization is itself a historical formulation, however, does not tell us anything about its accuracy. By charting a variety of other words in the Ngram Viewer, we can compare their relative prominence, asking if they too support the construct of a significant change. The results show that some do and some don’t, and many words evidence uneven patterns and varying trajectories, all adding complexity to the notion of a divide. At least five differing patterns emerge.

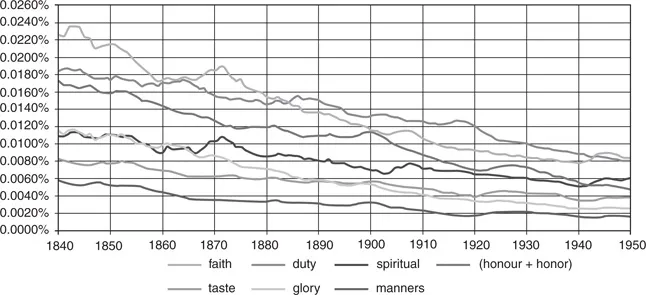

Many words that we associate with Victorianism manifest decreasing prominence in print between 1840 and 1950, but gradually, not abruptly, suggesting a pattern of shifting emphasis rather than radical change. In addition to faith, duty, spiritual, hono(u)r, taste, nation, glory, and manners, less culturally inflected words such as nature, love, and hope also indicate decreasing use (a selection is shown in the graph) (Figure 1.3).

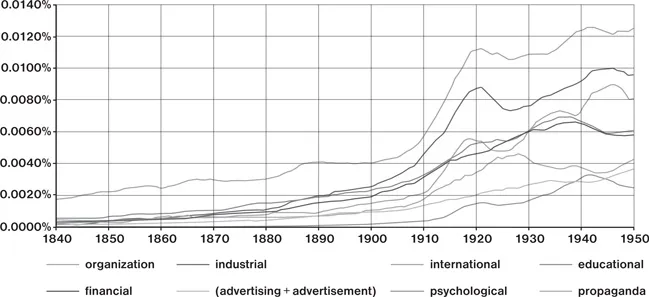

Some words that we readily associate with modernism suddenly increase in use. If nation declines gradually, internationalism rapidly acquires prominence following World War I. After 1910, advertising and propaganda emerge as significant words, reflecting distinctively twentieth-century concerns pertaining to mass communication and mass culture. An increasing emphasis on productivity and business is reflected in words such as organization, industrial, and financial, while the rise of words such as psychological and education reflects growing interest in human development (Figure 1.4).

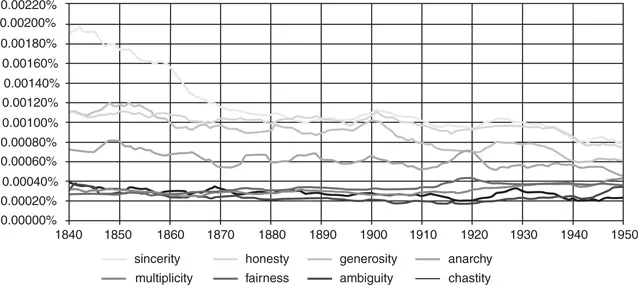

While the above two patterns are indicative of gradual and sudden change, some words commonly associated with one or the other era remain relatively steady in use. Sincerity (after 1870), honesty, generosity, fairness, and chastity are equally modernist as well as Victorian concerns, while anarchy, multiplicity, and ambiguity are as equally Victorian as modernist. At higher levels of usage frequency, general terms like time, human, and, perhaps amusingly, weather are strongly consistent as well (space shows a slight increase). Of course, the values attached to these words may be differently interpreted, but the words themselves articulate a pattern of shared concerns (Figure 1.5).

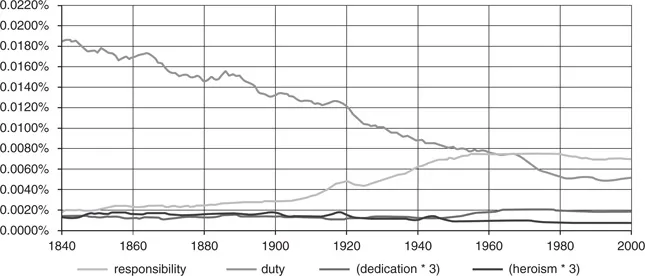

Expanding the time scale to the year 2000 reveals yet another pattern: instead of a diminishing concern, a declining word may be signaling its incipient displacement by a comparable, though differently inflected term. Whereas duty declines, responsibility rises, the two lines crossing in the mid-1960s (Figure 1.6). On a slightly lesser scale of frequency, whereas courage declines, leadership rises, the two lines crossing in the late 1930s. We need to graph an extended period of time to expose such patterns, but the processes they suggest are of reorientation and redefinition, rather than radical change.

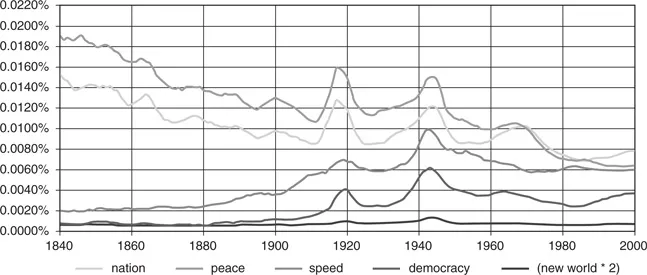

Another striking pattern shows up clearly in Figure 1.7: word bulges, which I call war humps, revealing local and temporary effects of the world wars. Not surprisingly, war itself is the word that most dramatically evidences these humps, such that its high frequency would mask the pattern in words less frequently used (interestingly, war does not manifest such humps in the nineteenth century). Once we omit war from the graph, however, peace, nation, and democracy (even speed) all display significant war humps too. The graphs here detect the cultural ripples generated by war, as embedded smaller-scale patterns in twentieth-century concerns.

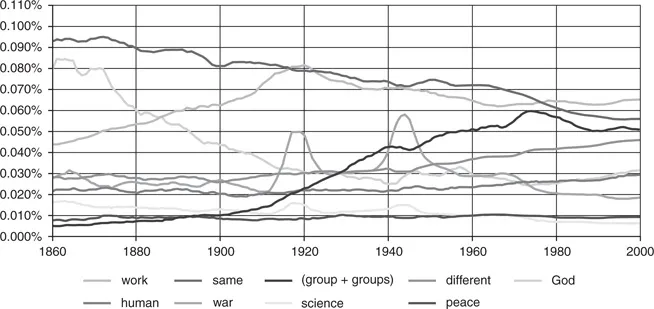

Combined and superimposed, the graphs prompt us to visualize a composite and complex figuration of history, beyond the Victorian/modernist divide. Figure 1.8 is palimpsestic, comprising multigrid patterns of descending, ascending, steady, and bulging lines that also proceed at different speeds. While reference to God declines rapidly from 1840 to 1920, this descending line is crossed by the rising trajectories of work and group(s), the first crossing in the mid-1880s, the second in the late 1920s (the graph here begins at 1860, since the high frequency of God in 1840 would mask the other words lesser in scale). After 1920, however, God continues to be used with approximately the same frequency and is still higher than human, war, science, and peace at the putative modernist period’s end. War exhibits those characteristic war humps, as does peace in lesser degree, while human and science are relatively unchanged. In another interesting pattern, the fall of same is matched by the rise of different – a pattern that continues to the century’s end (a similar pattern appears for new and old, with the former crossing the latter about 1913). The model does not deny the radical break theory of modernism, but it shows such breaks to be embedded in, and in interaction with, numerous divergent lines. Radical change is one part of a complex, multidirectional flow.