![]()

p.1

1 Introduction

Conservation and development in India

Shonil Bhagwat

Background to this book

Kalidasa, a fifth-century Indian poet, imagined Meghaduta, the Cloud Messenger, drifting over the Indian subcontinent. On its journey from the south to the north, Meghaduta reports many beautiful landscapes on its path, where people live in peace with their natural environment. Today one can follow the same journey on Google Earth (Figure 1.1). As one travels from south to north over the subcontinent, the densely populated coastal cities and towns give way to the lush green forests and plantations of the southern Western Ghats. Even the remote forests are dotted with villages and small settlements. There are reservoirs for storing water, clearings in the forest for farming and food production, and the mining operations in the rugged rocky hills of the Eastern Ghats. On the way to the central plains of India, there are rivers criss-crossing the Indian peninsula and without perennial water many riverbeds appear dry until the monsoon rains arrive each year. The central plains are dotted with trees, woodlots and plantations, some of them protected by communities for timber, fuelwood, fodder and shade for their livestock. The sandy desert landscapes of the north-west strike a contrast with the lush green mountains but even there the countryside is dotted with trees, some of them sacred to people. As one approaches the river deltas and the Himalayan foothills, yet again the landscape strikes a distinct note as the forests of the mountain slopes return. Moving further north along the towering Himalaya, and as one moves higher up the mountain range, the rugged landscapes carved out by the mighty glaciers over the geological past strike yet another distinct note and bring us all the way to the ‘roof of the world’ with some of the world’s highest mountain peaks.

Looking at the landscapes of the Indian peninsula from a bird’s eye view, the agricultural, ecological and technological transformations that the country has witnessed through its history become evident. This provides a backdrop for the conservation of wilderness in this highly populated country, alongside development of its still largely rural population, which in some cases is entirely dependent on agriculture. The post-colonial history of Indian conservation and development sets the scene for current conservation issues in India. In particular, despite decades of efforts to integrate conservation and development elsewhere in the world, India is still torn between two very different worldviews of peoples’ place in the country’s natural environment. Conservation in India is increasingly concerned with creating ‘wildlife theme parks’ – inviolate, albeit isolated, spaces for wild nature that have become a tourist attraction where the urban elite can seek entertainment through wildlife-watching (as the picture on this book’s cover photo portrays). On the other hand, development is concerned with fast-tracking mining, construction and other infrastructure development projects that also serve the interests of the urban elite. Simultaneously, nationwide welfare programmes have made promises of food, clothing and shelter for the poorest of the poor living in rural India, but they have rarely delivered on these promises. Conservation and development therefore are both mainly for the elite. Even though they are serving the same constituents, the motivations for the two are very different and attempts to find common ground between them have been fraught with challenges.

p.2

Finding this common ground has been particularly challenging on the fringes of wildlife parks, where the rural poor come in frequent contact with wild animals to the detriment of both people and wildlife. Can the ‘wildlife theme parks’ and the fast-track development model be reconciled with the needs of the poor or will the rift between conservation and development continue to widen as the country embraces modernity? This book takes a critical look at the conservation of nature and the alleviation of poverty in the Indian setting. It aims to open up discussion of the conservation–development nexus in a country that stands at major cross-roads – with forces of neoliberalism, globalisation and urbanisation driving the future of India’s environment. The book unfolds through chapters written by leading scholars on Indian conservation and development, and it attempts to paint a picture of the future of nature conservation in India by engaging with key debates. While focused on India, we envisage that this book will be of interest to scholars and researchers well beyond. As a ‘rising power’, the world’s eyes are set on India’s development trajectory and there is unprecedented interest in the course of development that the world’s largest democracy will take in the decades to come. This book provides a fresh look at the conservation–development nexus, charting the way forward for Indian conservation in the twenty-first century.

p.3

Conservation beyond parks

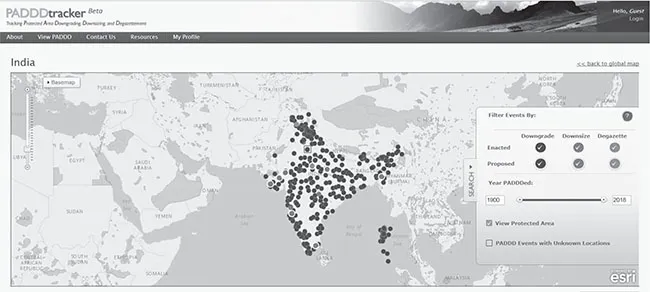

The history of the Indian conservation apparatus is deeply rooted in its colonial past. More than six decades after Independence, the protected area network in India has expanded, but nature conservation is still closely associated with its national parks and wildlife sanctuaries, many of which are former hunting preserves. This brings with it many challenges, not least the conflict between the interests of parks and those of people. This ‘parks vs people’ or ‘tiger vs tribal’ issue has informed a lot of the discussion on Indian conservation and development. The challenges of marrying the interests of parks and people both have seemingly compromised the integrity of state-led conservation areas. PADDDTracker.org, for example, monitors the downgrading, downsizing and degazettement of protected areas all over the world. The country profile for India in Figure 1.2 shows the protected areas in India that have been ‘PADDDed’. As of July 2017, this database has recorded 510 PADDD events with over 8,500 km² downgraded, downsized or degraded. Common reasons for PADDDing include subsistence needs, infrastructure development or new settlements. This map presents a stark picture of pressures on Indian protected areas as the country tries to balance conservation with development.

p.4

Addressing PADDDing requires looking beyond protected areas and finding novel solutions to challenges of doing conservation in a highly human-dominated landscape. But how can charismatic megafauna co-exist with people when the two are coming into increasing conflict with each other? Some instruments of this new conservation approach include creating new incentives for people to tolerate wildlife, e.g. revenues from ‘ecotourism’. Other instruments include new categories of protected areas such as ‘indigenous and community-conserved areas’, based on existing conservation ethos among local communities. But ultimately, the future of Indian conservation depends on whether or not people are able to live with wild animals in their backyards. This requires new ways of thinking about the interactions between humans and wild animals. It also requires the acknowledgement that the need for humans to share space with wild animals is rooted in how conservation and development are conceptualised. Conservation and development in India in turn are themselves situated in the wider discourses on sustainability and a wide range of other environmental issues. The discussion on sustainable development is therefore relevant to the wider context of conservation from perspectives in environmental change, renewable energy, sustainable wellbeing and the Anthropocene. These concepts will inform the future of conservation and development and the future of shared spaces between humans and wild animals.

Conservation with people

With substantial investment from the state in wildlife conservation, parks are arguably still the cornerstones of nature conservation in India, but they have historically disadvantaged certain groups of people, particularly those who live in close proximity to them. In a country that is on a trajectory of rapid economic development, parks are increasingly catering for the elite urban citizens of India, often acting as ‘wildlife theme parks’ where the elite tourists can regain their lost contact with nature. A large portion of the Indian population, however, does not fall into the elite category, but ekes out a living from natural resource-based occupations, primarily subsistence agriculture, gathering and, in small proportions, hunting. How does Indian conservation play out for their livelihoods? How do the welfare policies for assuring food, clothing and shelter to the poor influence their relationship with natural resource-based occupations? And how do these policies interplay with conservation outside protected areas? This book takes a look at the new policy instruments such as people’s right to access forest resources and examines community-based conservation and joint forest management, for which India is known as the leading example, in this context. Attention is also paid to the surge in market-based instruments such as payments for ecosystem services that aim to bring parity between urban elite citizens and subaltern rural communities by aspiring to transfer some economic wealth from the rich to the poor.

p.5

Politics of conservation

As a rising power, India has captured the world’s imagination for its rapid economic development since the 1990s, when the Indian economy was dramatically transformed by neoliberal economic policies. India’s status as a rising power brings with it a sense of national pride that often manifests in the conservation focus on India’s charismatic megafauna. The wider Indian political economy also plays a role in determining India’s development trajectory through, for example, ambitious national programmes on rural development, employment guarantee or food security. The conservation–development nexus operates within this broad context and is often enabled or compromised by the political setting. So how does the political setting influence conservation? In this context, the politics of a wide range of conservation issues is important: ecosystem service trade-offs, invasive species management, non-timber forest products etc. This also determines the politics of parks, people and their interplay. The book proposes that new ways of thinking about conservation and development are necessary as the Indian economic power continues its upward trajectory. In particular, it critically examines the ways in which parks and people might co-exist in the future. It asks whether such reconciliation is possible and if so in what ways.

Concepts in this book

The book critically engages with a number of key contemporary concerns and opens up new lines of enquiry through empirical case studies. These include the concept of the Anthropocene – the notion that humans have been responsible for a new geological epoch; the range of interactions between humans and non-human species on a human-dominated planet; areas that are protected by people through their own ethical outlook to sharing space with other species; the challenges in governing such areas; and incentives for people to do conservation in places where they live, work and play.

The Anthropocene

The concept of the Anthropocene signals the influence of humans on the Earth’s ecosphere and the signature it has left in the Earth’s geosphere. Scientists have been preoccupied with finding a precise date for the beginning of the Anthropocene (Zalasiewicz et al. 2015) and suggestions vary from as far back as 11,500 years ago when the evidence of first land clearing for agriculture emerges (Ruddiman 2003; Ellis 2015), to as recently as 16 July 1945 when the first nuclear test was carried out (Steffen et al. 2015). But it is not just the time of its beginning that varies; what also matters is where on Earth you are. If the Anthropocene started in New Mexico, USA (where the first nuclear test was carried out) in 1945, did it start in India on 18 May 1974 when the first nuclear test was conducted in Rajasthan? Much as the start of the Anthropocene varies in time, it may also vary in space (Damodaran, this volume). If the signature of the Anthropocene is widespread human activity, then this goes back to 10,500 years ago, when Neolithic farmers started the cultivation of barley and wheat in north-west India (Gangal et al. 2014). On the other hand, despite a long history of human settlement, the Indian subcontinent remains home to some iconic megafauna including Asian elephant, rhino and tiger. This is in contrast with the megafaunal extinctions during the Pleistocene across much of the world, partly driven by the arrival of humans on hitherto uninhabited continents and, since then, substantial human influence on landscapes wiping out many species including through hunting and habitat destruction. Bearing in mind the rich diversity of megafauna that is still extant in India, it can be said that the Anthropocene is yet to arrive. However, the wave of modernisation and neoliberalism in India with capitalist resource extraction may have an adverse effect on the grassroots conservation ethic that has saved species from going extinct up until now.

p.6

The Anthropocene has another dimension. It is also about creative engagement with novel nature. Human activity transforms the so-called ‘pristine’ ecosystems to anthropogenic landscapes giving rise to novel ecosystems – novel in their composition, structure and function. Examples of novel nature can be found in India’s cities, vill...