![]()

1 Introduction

The Gallipoli peninsula is a spit of land, 33,500 hectares and 80 kilometers long, which is located on the North Anatolian Fault zone and forms part of the Alpine Pontide range. It delineates the northern border of the Dardanelles, the waterway that connects the Marmara Sea to the Aegean, while separating the two continents of Europe and Asia along the fracture between the European and Anatolian tectonic plates. The peninsula takes its name from Ancient Kallipolis, “the Beautiful City,” which is now the Turkish town of Gallipoli located at the far northern entrance to the peninsula.1 Across the Dardanelles from the Gallipoli peninsula is the Troad, the lands containing Priam’s legendary city of Troy, now an archaeological park and World Heritage site.2

Today in Turkey the peninsula is referred to as the Gelibolu Yarımadası—literally, the “half island” of Gallipoli. The strait, which at its narrowest point is twelve hundred meters, is known as the Çanakkale Boğazı, or the “throat” of Çanakkale, and is the location of the largest city on the Asian shores of the Dardanelles; in 2017 it was home to half a million residents. The construction of the Çanakkale 1915 bridge, which will connect the European and Asian shores of the Dardanelles, began on 18 March 2017, the anniversary of a symbolic Ottoman naval victory in the Çanakkale Wars. The world’s longest suspension bridge is expected to be completed by 18 March 2022 and is intended by the government as a major stimulus for the development of tourism and industry in the region.

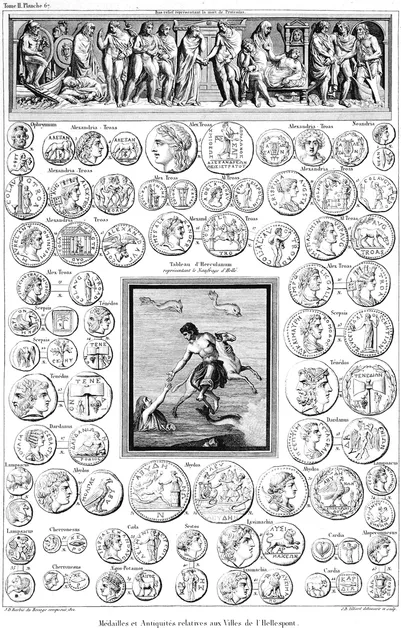

In the sixth century BCE the Gallipoli peninsula was referred to as the Chersonese, and the waterway that separates the Asian and European continents was known as Hellespontos, or the Sea of Helle, after the Classical mythological figure of Helle, a consort of Poseidon. Helle and her brother Phrixus were assisted by their mother to avoid the wrath of an evil stepmother by escaping on the back of a flying golden ram; but Helle lost her grip, fell to her death and drowned in the waters of the straits (Figure 1.1). While we lack sufficient archaeological data from the region to provide a comprehensive chronology, the surveys and archaeological excavations that have been undertaken on the peninsula in the past century indicate that humans have lived there since the Prehistoric era.3 The Antique sites on the shore of the straits facing Asia, such as Elaious, are mentioned in the writings of many Classical and Roman-era chroniclers and geographers. Excavated by the French during World War One, and again between 1920 and 1923, the necropolis of Elaious revealed an abundance of artifacts and sarcophagi.4

Figure 1.1 Image in the center shows the fall of Helle into the sea, surrounded by the coins of the ancient cities around the Hellespont. From “Médailles et Antiquités relatives aux Villes de l’Hellespont” in Choiseul-Gouffier’s Voyage pittoresque de la Grèce, Paris, J.-J. Blaise, 1822.

Credit: Aikaterini Laskaridis Foundation

Famous crossings of the straits were undertaken by the armies of Persian warrior kings Darius I in 514 BCE and Xerxes in 480 BCE, the latter with boats strapped together to create a pontoon bridge for his invading troops. In 334 BCE, Alexander the Great, while conquering Thrace and then the Gallipoli peninsula, is alleged to have made a pilgrimage to a remote site at the end of the peninsula to pay homage to the mythic Greek hero Protosilaus, among the first to fall in the Trojan War.5 Later Byzantine and Ottoman rulers recognized the strategic value of the peninsula and erected fortresses and customs houses along its shores to keep pirates and enemies, such as the Venetians and later the Russians, at a safe distance from the capital of Constantinople; and to collect revenue from the lucrative trade that passed from the Black Sea to the Mediterranean and back.6

Due to its strategic location bordering the Dardanelles, the Gallipoli peninsula has been the site of many conflicts in its long past. However, it is best known as the location of one of the major battles fought in World War One by the Allied forces—comprised of the French and Commonwealth troops—against the Ottomans and their German allies. Divided Spaces, Contested Pasts: The Heritage of the Gallipoli Peninsula examines the heritage of the post-WWI landscape, its archaeological and commemorative projects, and the political agendas which have shaped the past and the present of the Gallipoli peninsula since 9 January 1916, the day that marked the evacuation from the peninsula of the last of the defeated Allied forces.

The Gallipoli peninsula: a brief history since World War One

Conflicts between the Ottomans and the Allied forces during World War One began in November of 1914 when the coastal fortresses of Seddülbahir and Kumkale, part of the defense system at the Aegean entrance to the Dardanelles, were bombarded. The actual land invasion that has come to symbolize the beginning of the Gallipoli campaign in World War One (known as the Çanakkale Wars in Turkey), and the day that is commemorated by Australians and New Zealanders as ANZAC Day, was 25 April 1915.7 The main reason for the invasion of Allied forces in this southern European theater of war was that the offensive against Germany on the European Western Front had ground to a standstill early in 1915. The intention of the Allied forces was to open a new front in the east and establish a safe supply line between their ally Russia and the Mediterranean Sea. Russian access to this warm water port was crucial for the Allied troops as the Tsar’s munitions and shipments of grain were essential to the success and sustenance of their European armies. Both Lord Kitchener, British Secretary of State for War, and Winston Churchill, First Lord of the Admiralty, supported a plan to attack the Gallipoli peninsula. This strategy, however, required that the Allied navy first capture the straits of the Dardanelles and then move north to the Bosphorus to take the capital of the Ottoman Empire, known then as Konstantiniyye, or Constantinople.

The Allied forces did win World War One, but the plan to take the Gallipoli peninsula from the Ottomans failed and has been recorded in history as a disaster of epic proportions in terms of its poorly planned military strategy, implementation, and resulting casualties. After nine months of fierce fighting on the peninsula between the Allied and Ottoman troops, the battles ended, the Ottomans were victorious, and the Allied troops quietly evacuated. The total number of casualties in the Gallipoli battles was close to half a million. The exact number of dead is still debated on all sides, but estimates are that at least 22,000 British and Irish, 7,500 Australians, 2,700 New Zealanders, and 10,000 French died on the Allied side. The majority of the Allied troops had been conscripted from England and France but there were also soldiers from Canada, Ireland, Scotland, Wales, India, Malta, Tunisia, Algeria, Gambia, and Senegal who were part of the Allied forces. On the opposing side, up to 130,000 Ottoman soldiers are thought to have perished during the years of combat.8 Among the Ottoman troops there were also soldiers of diverse ancestry, including Arabs, Greeks, Armenians, Kurds, and Jews.

The Greek and Turkish civilian populations living in the villages on the Gallipoli peninsula either fled or were evacuated just prior to the major battles that began there in 1915. The few Greeks who returned to their homes in the villages on the peninsula when World War One ended on 11 November 1918 did so for a short time only; most emigrated permanently after the major Greek defeat in August 1922 during the Turkish War of Independence.9 After the signing of the Treaty of Lausanne on 24 July 1923, problems related to the exchange of peoples and properties between Greece and Turkey, known as the 1923–24 Population Exchange (Türkiye-Yunanistan Nüfus Mübadelesi), were extensive and the archives are full of court suits on both sides from plaintiffs, some of whose fields and homes were expropriated by the Allied or Turkish governments to use as land for commemorative monuments and cemeteries.

Identification, exhumation, reburials, and commemoration of those who had died on the Gallipoli peninsula during World War One occurred during the war, but both the Allied countries and the Ottomans began a more organized and official process of dealing with their dead in 1918, after World War One had ended. By 1915 the British had formed the Graves Registration Commission as part of the Red Cross; the former organization would evolve in 1917 into the Imperial War Graves Commission (IWGC) and subsequently into the Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC), which by 1926 had concluded a formidable project on the Gallipoli peninsula resulting in 31 cemeteries and 6 commemorative monuments complete with extensive landscaping. To date, close to 23,000 graves have been individually marked in the many CWGC cemeteries throughout the peninsula; approximately 9,000 of these contain the remains of soldiers who have been identified. Thirteen thousand of the dead are buried in what the CWGC refers to as “concentration” cemeteries, near the locations where their remains were found. The remains of more than 14,000 soldiers were never found; they are commemorated by name on the Helles Memorial (British, Australian, and Indian), the Lone Pine Memorial (Australian and New Zealand), the Twelve Tree Copse, Hill 60, and Chunuk Bair Memorials (New Zealand).10 The French troops who lost their lives fighting at Gallipoli also had several burial sites on the peninsula during the war, including a cemetery in the Ottoman fortress at Seddülbahir, but these were concentrated after the war into a larger cemetery at Morto Bay, with burials in both individual graves and ossuaries.

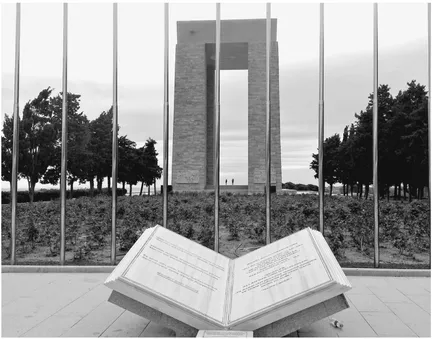

The Ottomans also buried their dead during the war, and they created cemeteries and memorial structures both on and off the peninsula at that time. Some of these were makeshift structures which have been lost, destroyed, or heavily reconstructed. Many of the Ottoman soldiers who perished while fighting in the Çanakkale Wars were buried in mass graves which are still being discovered today with the help of archival military maps and non-invasive archaeological technologies. A more substantial national campaign to commemorate the Ottomans who had died while fighting on the peninsula in the Çanakkale Wars began two decades after the Turkish War of Independence with the submission of plans for the Çanakkale Martyrs Memorial in 1944, an immense commemorative complex referred to today as the Abide (Figure 1.2).

Figure 1.2 The Çanakkale Martyrs Memorial (Abide).

Credit: Archive of L. Thys-Şenocak

Just before that campaign, in the 1930s, the migration of Turks from the Balkan regions of eastern Europe into western Thrace, which had begun in the late nineteenth century, accelerated as the result of the relative stability in a region that had seen so much demographic displacement and upheaval during the Balkan Wars, World War One, and the Turkish War of Independence. Turkish refugees, the majority from Romania and Bulgaria, continued to arrive in the new lands of the Turkish Republic through the 1940s. Many from Romania repopulated the villages on the Gallipoli peninsula, while the majority of the Bulgarian Turks settled in the villages of the opposite Asian shore.11 Most of these new migrants survived by farming among the makeshift graves of the dead who were buried in their fields, and by selling the salvaged ordnance that remained from the war. Many built their first homes on the peninsula by harvesting the crumbling masonry from nearby Ottoman or World War One military structures, and by melting down ordnance left behind from the war.12

In the decades that followed, proposals were made to create a national historical park on the Gallipoli peninsula, but it would not acquire that official status until 2 November 1973. The groundwork had been laid for the formation of national parks in Turkey in the mid–1950s with the establishment of non-governmental organizations such as the Foundation for Turkish Nature Conservation (TTKD) in 1955, and the approval by the Turkish government of the 1951 Agreement on the Establishment of European and Mediterranean Plant Protection Organization. By the 1970s, the environment and its protection had become an official part of Turkey’s 1973–78 Five Year Development Plan.13 The formation of Turkey’s first national parks was the result of collaboration in the late 1960s between the United States National Park Service (USNPS) and the State Planning Organization in Turkey, under the direction of the head of the Turkish National Parks Department, M. Zekai Bayer. This project, a USNPS and United States Agency for International Development (USAID) effort, was intended to create plans for twelve national parks ...