- 158 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

First published in 2001. Routledge is an imprint of Taylor & Francis, an informa company.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Gender, Ethnicity and Market Forces by Sheena Choi in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Higher Education. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter One

Introduction

Problem Statement

In modern society, education is often seen as a vehicle of social mobility. While the myth of social mobility through education may be exaggerated, the value of schooling for socioeconomic attainment is well established (Olneck, 1995). Especially for immigrant children, schooling has been considered “an avenue out of poverty and into the middle class” (Olneck, 1995, p. 322).

Guskin (1965, p. 151) notes “The effect of the school on the identity, attitudes and aspirations of the students is quite understandable” for “almost every society, the educational institutions represent the major socialization institutions for youth. At an age when individuals are most susceptible to alterations in their identity, the school presents a rather consistent picture of desired behaviors. Also, the school is the major agency of society for training in new skills and areas of knowledge which will enable the adolescent to adapt to the larger society.” Schools thus take over from the family the socializing function. Assimilation which is an element of socialization “refers to the process whereby one group, usually a subordinate one, becomes indistinguishable from another group, usually a dominant one” (Feinberg and Soltis, 1992, p. 25). Therefore, schooling has historically presented and continues to present a challenge to the values and heritage of immigrant groups (Olneck, 1995). The dilemma of whether to assimilate or to maintain an ethnic identity has had profound consequences for immigrant families, often disrupting relationships between generations by transforming the cultural values, practices, and identities of each generation. For this reason, the schooling process sometimes becomes a source of tension, discomfort, and conflict between first-generation immigrants and their native-born offspring. In less developed societies, even primary level education can result in a separation between children and parents, while in developed societies, such as the United States, Western Europe, and Korea, higher education opens the door to a profession, thus, social mobility. In certain respects, these same attitudes influence educational choices, especially those regarding higher education, made by ethnic Chinese in Korea.

The schooling of immigrants and ethnic minorities thus holds substantial “symbolic power” (Olneck, 1995, p. 310) for both the majority population and its minorities, as it reflects the historical context and the philosophy that inform a given society. In the case of ethnic minorities, the relationship between schooling and cultural values is even more complex, for education often acts as a homogenizing force to integrate immigrant youth into the mainstream language and culture. For this reason, “research on immigrants and education illuminates important societal beliefs and aspirations, prevailing educational policies and practices, and contentious debates about multiculturalism” (Olneck, 1995). In the case of the United States, which is a heterogeneous society, educators’ responses to immigrants in the early part of the twentieth century led to the notion of “Americanization” as the goal of education for immigrants. They “thought to promote cultural conformity in order to integrate the population and to enhance immigrants participation in national life” (Olneck, 1995, p. 312).

Korea, which has very small numbers of minorities, is a unique case because it is known as one of the most homogeneous societies in the world. The ethnic Chinese who arrived in Korea at the turn of the twentieth century represent the single largest ethnic minority group, comprising less than one percent of the total Korean population. The title “invisible minority” refers to several elements: small population and indistinguishable physical characteristics with the host population, which make them able to blend into the host society more easily if one chooses, than racially different groups, such as African-Americans in the US. Although ethnic Chinese in Korea have not been traumatized from the dominant society, this minority population’s invisibility stands out in their preclusion from the political and economic arena of Korean society.

The ethnic Chinese in Korea calls himself or herself Han-Hua, which means Korean-Chinese or simply Huaqiao. In this study I will use the English and Chinese term Korean-Chinese, Huaqiao, and Korean-Huaqiao interchangeably. There are numerous way to spell “Overseas Chinese” and Huaqiao(s). For my purpose, I will use “Overseas Chinese” and Huaqiao(s), which may differ from others’ spelling of these words.

Following the Korean War (1950-1953), the ethnic Chinese were unable to return home to China and, at the same time, there was no fresh influx of immigrants to Korea. Thus, the majority of ethnic Chinese in Korea belong to the generation of those who were born and grew up in Korea.

Korea is an “economic miracle” that has achieved an incredible record of growth. Three decades ago its GDP per capita was comparable with that of the poorer countries of Africa and Asia, such as Ghana and Indonesia. Beginning in 1962, however, Korea launched a series of five-year economic development plans, resulting in Korea’s emergence as one of the leaders among developing countries as it has become more urban and industrialized. Today its GDP per capita is eight times India’s, fifteen times North Korea’s, and is already comparable with the weaker economies of the European Union (CIA World Fact Book, 1998). Economic strength has enabled Korea to successfully host the Asian Games in 1986, the Olympics in 1988, and the Taejon EXPO ‘93. Korea has also elected to co-host the 2002 World Cup with Japan. All of these events demonstrate remarkable political, economic, social, and cultural progress. Korean education has also experienced extraordinary growth: quantitative expansion from the 1960s through the 1970s and qualitative development in the 1980s. This growth in education is credited as the driving force behind Korea’s national progress and growing international prestige, producing the workforce needed for industrialization and democratization.

Korea’s rising economic power has had a significant impact on the relationship between the ethnic Chinese and the larger society. When Korea was a colonized nation and economically underdeveloped, the more affluent ethnic Chinese remained aloof from Korean society. But as the economy developed and the nation grew politically more stable, this minority group could no longer maintain its separateness but rather sought to develop stronger ties with the larger community.

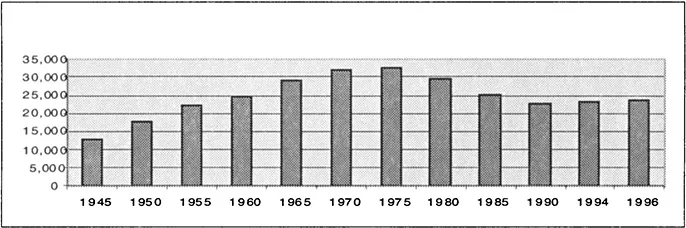

Rapid economic growth is often followed by an influx of immigrants (e.g. guest workers in Western Europe), and, in most cases, the second generation decides to stay in the host nation. However, in Korea the minority ethnic Chinese population decreased during the prosperous period of the 1970s through the 1980s (see figure 1).

Figure 1: Numbers of Huachiaos in Korea from 1945 to 1996 (eve)

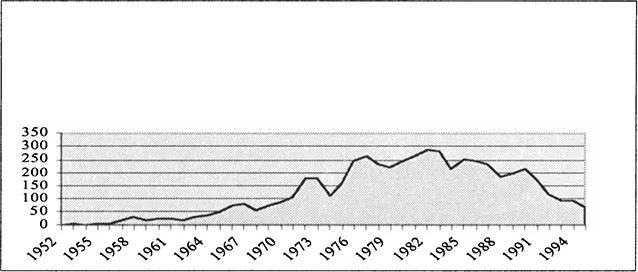

According to the Korean Ministry of Justice’s 1996 Annual Report of Statistics on Legal Migration, there are 23,282 ethnic Chinese residing in Korea as legal aliens. Moreover, many ethnic Chinese in Korea believe that about 7,000 to 8,000 resident Chinese people in Korea are floating members, residing elsewhere but keeping resident alien status in Korea. Thus, the actual number of ethnic Chinese in Korea is approximately 15,000, with some estimates as low as 10,000 (The Economist, 1996). One study claims that Korea had the greatest loss of its ethnic Chinese population (seven percent) during the 1980s (Poston Jr., Mao, & Yu, 1994), with the result that there was a decrease of more than fifty percent since the 1970s (Kukmin Daily, Aug. 24, 1992). This population decrease was due to Chinese emigration rather than to the effects of low fertility or high mortality. Rather than entering Korean universities, ethnic Chinese students opted for Taiwanese universities upon graduation from their ethnic secondary schools. Admission to Taiwanese universities was often utilized as a way to emigrate to Taiwan: it was an opportunity to settle in Taiwan and bring over the remaining family members from Korea upon graduation. The ethnic Chinese in Korea claim that various adverse political and economic forces have led to emigration of the Chinese population from the host country (see figure 2). Further, the majority of ethnic Chinese in Korea has been vague about staying in Korea, while strongly defining themselves by their ethnic identity.

Figure 2: Annual Number of Korean-Huachiaos Who Graduate from Taiwan Universities (1954-1996)

Source: Overseas-Chinese Commission (1999)

Source: Overseas-Chinese Commission (1999)

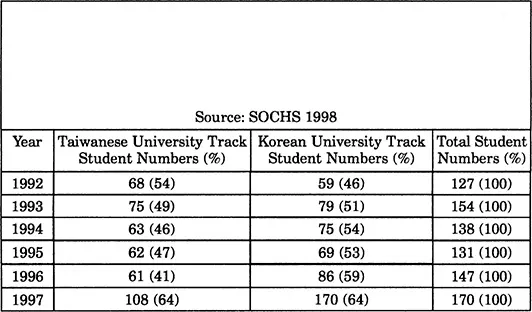

Such a trend began to reverse during the Seoul Olympics of 1988, and as a result, at present, approximately seventy percent of ethnic Chinese students upon graduation from ethnic secondary schools prefer to study in Korean universities as opposed to Taiwanese universities (see table 1).

Table 1: Seoul Overseas Chinese High School (SOCHS) Seniors in Taiwanese University Track and Korean University Track

Students who apply to Korean universities are exempted from taking competitive entrance examinations, as Korean students must. Although the Chinese claim that they experience discrimination in employment opportunities, they are now choosing to stay in Korea after graduation. While more business opportunities have developed in China and there are more possibilities to travel abroad, including to the United States, Taiwan, and China, not many Korean-Chinese have resettled in China and elsewhere. The Chinese population in Korea is stabilizing, a trend that coincides with the increasing enrollment in Korean institutions of higher education.

Therefore, the concept of college choice has largely two meanings: the choice of individuals, which has the more conventional meaning in US literature; and the choice of minority communities, which shapes their decision regarding special schools for their children. The shift in Korean-Chinese students' preference for Korean rather than Taiwanese universities may reflect their changes in perceptions on both the individual and community level (e.g. improved opportunities such as fewer political constraints, better economic incentives, and stronger social networks for the ethnic Chinese in Korea). This study will illuminate the impact of these political and social changes by focusing on the overarching question, “Why has there been a shift in the choice of higher education among the ethnic Chinese in Korea?” The following sub-questions were asked in order to answer the main research question:

- What is the state of majority/minority relations in Korea, and how does this relationship influence ethnic Chinese students' college choices?

- How does community choice influence individual choice?

- What were the Korean government's social, economic, and educational policies toward the ethnic Chinese since 1945, and how did these policies influence this minority's educational choices?

- What are the advantages and disadvantages of studying in Korean and Taiwanese universities?

- To what extent have Chinese students in Korea chosen Korean over Taiwanese universities?

- What do students, parents, teachers, and community leaders think has changed so those students now prefer Korean rather than Taiwanese universities? What are the implications of recent trends?

Comparative, historical, and policy perspectives will deepen the understanding of the changes in the Korean-Huaqiao students' choices in higher education. I employ a comparative perspective to investigate and compare, within a broader spectrum, the experience of the ethnic Chinese in Korea and minorities in other societies. In order to understand the characteristics of the Korean-Huaqiaos, I examine Chinese immigration to Korea from a historical perspective, and consider this phenomenon in light of modern Korean history. I also study the educational, social, and economic policies of the Korean and Taiwanese governments, which have played a critical role in the development of the present relationship between the Koreans and the ethnic Chinese. These various perspectives cannot be examined independently of each other because elements in each area have undeniably influenced the shift in educational choices among the ethnic Chinese in Korea.

Methodology

To deepen one’s understanding of this extremely small minority and the rationale for their choices in higher education, both a quantitative methodology, involving survey questionnaires, and a qualitative methodology, involving semi-structured interviews and document analysis, were used in this case study. Documents were collected from the archives of the Seoul Overseas Chinese High School (SOCHS), The Taipei Mission (unofficial diplomatic agent of Taiwan), various Korean newspapers, Korean and Taiwanese government documents, and other academic publications. A survey questionnaire was distributed to the entire senior class of the Seoul Overseas Chinese High School. Located in the capital of Korea, where sixty percent of the ethnic Chinese reside, SOCHS draws students from all over Korea, and thus, this school is composed of a more diverse student population than other regional ethnic Chinese schools. The collection yielded an eighty percent return.

A semi-structured interview was also employed. The purpose of the interviews was to understand ethnic Chinese attitudes toward education in the context of this population’s social milieu. Interviews with ten community leaders (including a newspaper editor and publisher, businessmen, physicians, university professors, and employees of Taipei Mission), twelve students, five teachers, ten parents of both Korean university-track and Taiwanese university-track students, ten alumni of SOCHS (five Korean university graduates and five Taiwanese university graduates), and numerous informal contacts with community members were conducted during the month of August 1998. Due to the extremely small size of the ethnic Chinese population in Korea, these samples adequately represent the community.

A second survey of SOCHS seniors was conducted in June 1999 (the same population group as the first survey) to collect more in-depth information. I have chosen SOCHS because of its easy access to me as an alumna, its larger population base, and its diverse student body as compared to other regional Overseas-Chinese schools.

Focus of the Study

The analysis behind this research emphasizes the experiences and perceptions of Korean-Chinese teachers, students, parents, alumni, and community leaders in order to understand their perception of reality and the basis for their choices of in...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- List of Figures

- List of Tables

- Acknowledgments

- Abstract

- Chapter 1. Introduction

- Chapter 2. Review of Literature

- Chapter 3. Methodology

- Chapter 4. Definition of Overseas-Chinese, The Korean Nationality Law and the Demography of the Korean-Chinese

- Chapter 5. Chinese Immigration to Korea and the Social and Economic History of the Korean-Huaqiaos

- Chapter 6. Huaqiao Education in Korea

- Chapter 7. Gender and Ethnicity in College Choices

- Chapter 8. Findings and Conclusion

- References

- Index