Analytical approaches and perspectives

Philippine contentions about Philippines-China relations in recent years have exemplified the need for China expertise. The first knowledge source that is often sought regarding the state’s approach to its bilateral issues with China is the pool of experts in foreign relations, security, and economics. Aside from the government sector and business stakeholders, other major producers and consumers of China expertise include think tanks/nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), academic units, and media. All these groups seek to exchange knowledge on China in response to a critical issue. While the salience of China knowledge need not be belabored, the evolution of such knowledge as a problematique needs elucidation. Two answers are foremost. First is the relatively expedient and practical usability of inputs when bilateral tension arises. That is, when there is a dearth of analytical response in certain aspects of the complex issue (e.g. integrated security-economic analysis), the nature of the expert knowledge production is queried. This practical use of China knowledge brings about both reactionary (i.e. how do we respond now?) and strategic (i.e. what needs to be done to build such critical knowledge) perspectives. Second is the contextualization of China knowledge as an epistemological reflection. The stance of the Philippines in analyzing and responding to China draws upon its stock of knowledge about it. While such a stance is a product of various social, political, economic, and historical dynamics, we accord keen attention on the knowledge of the thinkers who identify as China experts and the role of community in the generation of knowledge.

On this note, we begin with concepts of agency and context. There is a need to contextualize ideas among the thinkers from which they originate. The chief end of a historical inquiry is to delve into a past occurrence by looking at its external and internal reality in terms of “bodies and movements” and thoughts, respectively, not as mutually exclusive units but as a confluence of two dimensions represented by the agent’s actions (Collingwood 1946:213). Said in another vein, sifting through thinkers’ narratives, in which embedded meaning is related to individual decisions and internal negotiations, yields valuable insights on society and its oscillations from a broad structural view as well as from a personal view (Kaplan 2014:45, 49).

The thinkers’ intellectual engagement and how they interact with other thinkers captured in various forms of codification becomes important. We focus on oral histories as opposed to textual analysis to underscore the salience of the sociocultural space where values, worldviews, and aspirations are subsumed in the ethos of the thinkers’ eras (Cowan 2006:183). We situate the thinkers as actors in an idea-producing habitus faceted with sociopolitical layers and a system of practice—albeit with the attendant issues of subjectivism. We are interested in the phenomenological character of the experts’ evolving thinking as an actualization of their internal deliberations and their epistemic interaction with their environment (Boyer 2005:145, 148).

This work, then, problematizes the nature of the China knowledge of senior experts in the Philippines through an analysis of twelve individual narratives. In this chapter, China as a subject casts a wide net as it inclusively pertains to any aspect that relates to China, the Chinese, Chineseness, the overseas Chinese, and other related areas. In this sense, the thinkers who specialize in the Chinese in the Philippines are included in the scope of the China Studies community of practice. The article draws on the multidisciplinary lens of communities of practice, intellectual history, and knowledge management. Aside from the epistemological and ontological significance of constructively unpacking China expertise, the study is an input to understanding how this knowledge, through the community of thinkers that hosts it, affects the Philippines’ navigation of its relationship with its dominant regional neighbor.

Community of mavericks, knowledge, and practice

Mavericks as knowers

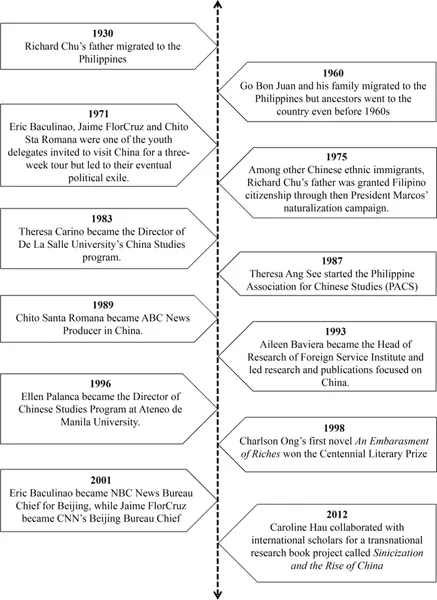

Following the semantics of Weisberg and Muldoon (2009:242, 244, 245, 250), we recognize the thinkers in this study as constituting a community of mavericks. Mavericks are distinct as they consider past approaches but seek to apply new lens in analyzing issues. Hence, the presence of more thinkers with a high sense of initiative and a strong trailblazing quality “drastically increases the epistemic progress of the community.” Since such thinkers push the limit of answering productive inquiries, their intellectual paths also experience substantial “epistemic progress.” As movers, mavericks are also able to influence the critical discourse—albeit in various capacities. Ang See, for instance, a pillar in the Chinese-Filipino community through her advocacies, which include integration, anti-violence, and anti-kidnapping efforts, is often invited as a subject matter expert and author for various China-related inquiries. Through these, she insists that she is not an academic. Oftentimes, the most fruitful discussions of China experts can be searched through the efforts of mavericks and their networks, even without formal organizing principles for such activities. In other words, the people are the main drivers. Adapting the framework of Brannen and Nilsen (2011), we present a timeline in Figure 1.1 that structures the thinkers’ personal details around the aspects of ethnicity, career trajectory, and leadership positions.

Figure 1.1 Timeline of Thinkers’ Selected Personal Details.

Community of knowledge

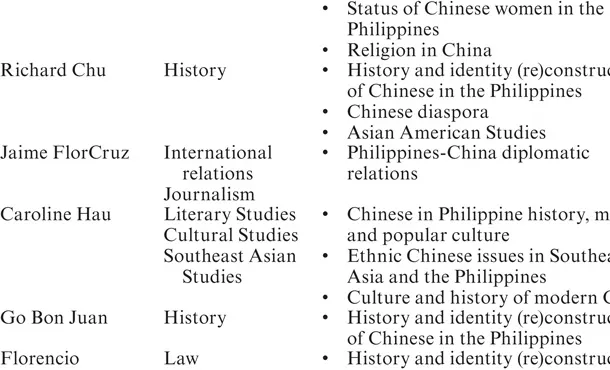

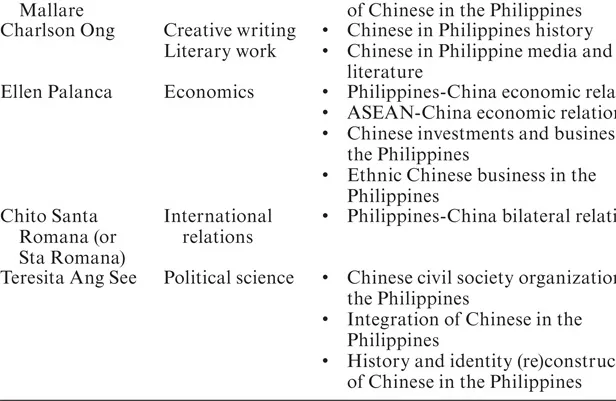

In contrast to a hierarchy and a market, the organizing principle of the thinkers in this study is that of a community where trust facilitates interaction. The deliberate organizational purview is oriented toward thinkers’ inputs rather than behavior/process or outputs. Tasks are contingent on each other, while knowledge and connections are exchanged in unspecific and tacit terms, allowing the stocking of favor for future invocation (Adler 2001; Cardona, Lawrence, and Bentler 2004). The emphasis of interaction is collegial collaboration and partnership within a loose structure, hence, collective networks also span wide local and international spaces. Oftentimes, many of them would insist that even a structure such as the Philippine Association for Chinese Studies (PACS), with which most of the thinkers in this study have been involved, is not an organization but a loose network of China watchers who ask each other for help in approaching a China-related issue. That aside, roles are determined by the contribution of specialized know-how, not authority or position. When one suggests, one gets the idea through by operationalizing it. These thinkers have a strong sense of individualist values but are, at the same time, collectivist (Adler and Heckscher, 2006; Galaskiewicz 1985:639). Table 1.1 shows the thinkers’ specialized China knowledge, related bodies of knowledge, and the issues of contemporary and historical significance that they respond to. These issues or more specific problematizations over time intersect with the thinkers’ lived experiences (Shoppes 2015:101).

Spaces of affinity and practice

The space of practice is curiously bound by affinity in interactions. In other words, personal bonds from having gone through similar experiences in history or bonds resulting from sustained interaction take primacy over explicit membership. In this sense, there is no significant need to define group belongingness. Explicit membership has become a formality processed in the most perfunctory manner, without attaching too much meaning. The community is not an imposition of structure but an ongoing experience that is expressed through social interaction. Self-identification as a China watcher facilitates the generation of China knowledge in negotiation with learning and practice. The more one shares knowledge on China as a resource person who engages the discourse, the more one deepens one’s China expertise and cultivates possibilities for self-identification as a China watcher. In this sense, self-identification as a China watcher contributes to determining the extent of one’s involvement in the community, with the thinkers’ agency at play in drawing on his views and beliefs as well as social influences on his/her thinking. On the other hand, the evolution of this self-identification is an outcome of sustained interaction and participation, affected by how the community evolves as well (Brown and Duguid 2001:200, 202; Thompson 2005:151–153).

Table 1.1 Thinkers’ China Knowledge and Epistemes

Similar pursuits create the space where new and experienced members participate. While some activities strongly facilitate strong knowledge generation, there are many ways that one can participate and be prominent (e.g. active and respected). Activities are driven by knowledge distribution, and the leaders themselves function as a resource for public intellectualism, the practice of which contributes to the endurance of the community as well as network propagation (Gee 2005:214–215, 225–228). Sustained practice as a facilitator of China knowledge generation becomes significant (Brown and Duguid 2001:198).

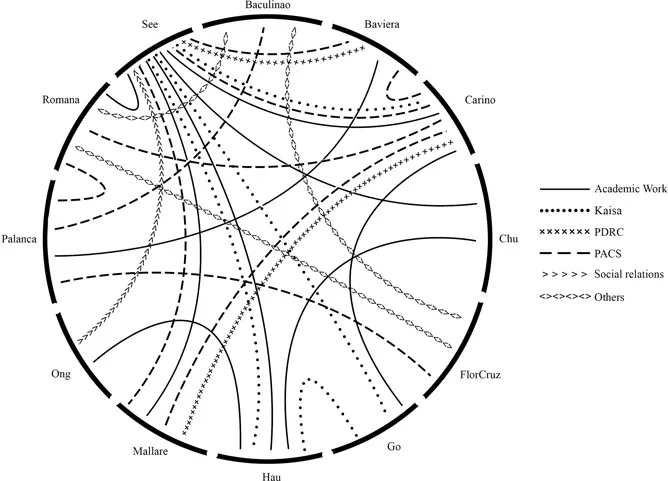

Figure 1.2 provides a simple example of a multidimensional community. While we emphasize that this mapping exercise is limited, it nevertheless provides a glimpse of what future network documentation projects can consider. The figure is based on a content analysis of details disclosed in the oral histories, such as long-standing social relations, common or related engagement, shared stories, and shared discourse. In the context of intertwining professional and personal linkages, thinkers also organize apt activities quickly in response to an issue, expressing familiarity with of the knowledge that the others can contribute. In engagements where the thinkers interact, regardless of the level of formality of the organizational structures that host events where knowledge is shared in a free-flowing manner, conversations are “the continuation of ongoing processes” (Wenger 1998:125–126). The figure shows an example of five interaction groupings. The groupings denote the facilitative mechanism of collaboration between the parties. Among the groupings, three are organizations—PACS, Kaisa Para sa Kaunlaran (Kaisa), and Philippine-China Development Resource Center (PDRC)—of which the last is now inoperative. The other two groupings pertain to academic work and social relations. Academic work includes publication in journals and attendance in conferences that were not hosted by Kaisa, PDRC, or PACS. The social relations grouping indicates friendly connections as colleagues, co-activists, and so on.

Figure 1.2 Affinity Space.

China watching and issues pursued

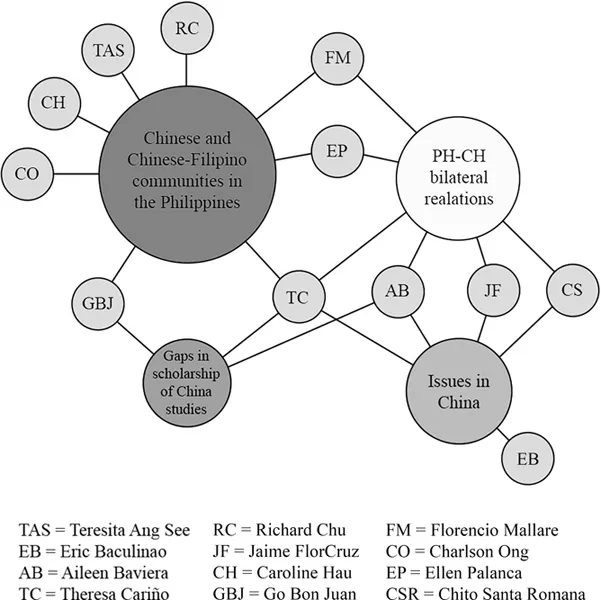

The China-related issues that the thinkers confronted are embedded in how they have negotiated their self-identification as a China watcher. This is whether the negotiation was explicitly thought out prior to the confrontation of the issue or practice of expertise, or a “preconceptual,” implicit post hoc realization. The nexus between such negotiation and how the thinkers made sense of realities that mattered to them draws on a set of knowledge (e.g. feelings, learning, acquired skills) while, in turn, producing knowledge. Knowledge as an employed resource functions as input for reflection and predicates action. As a produced resource, it becomes interactive in a social space; takes on particular forms as utilized by the community; and, to varying extents, can become conventional issue-specific knowledge. While the experts’ China watching can be generally categorized into four main categories (Figure 1.3), a more specific inquiry into the parallelisms among the thinkers in examining identity, pursuing issues, and viewing China reveals how much the thinkers shared a space of possibilities for learning from each other, consolidating their knowledge, and complementing each other’s expertise. In other words, differences in knowledge pursuits, given the affinity space, motivated, all the more, the need to interact and share know-how, whether this consisted of inside stories or action, such as organizing seminars (Barth 2002:1–2). The thinkers’ inception into China watching is interesting due to the diversity in motivations, which broadly cover questions on ethnic identity, ideology, and intellectual fascination.

Identity

Mallare was interested in finding out more about his identity. His work as a journalist brought this out further. He recalls,

Mallare saw that it was important to know oneself. He intimates that his passion to know was so strong that he went back to China to look for answers (Mallare 2015:29). While he became a known figure in publishing after he founded World News, a daily newspaper in the Philippines in the Chinese language, Mallare was able to combine his journalistic objectives and his pursuits as a China watcher, but he insists that being a scholar is not his main focus.

Figure 1.3 Main Categories of Studies.

Similarly, Chu’s journey to China was admittedly a personal quest to find his roots and learn more about his family as well as the larger milieu of China’s culture and people. While his motivations later spilled over to professional motivations, his primary push was still his question on identity, drawing from his experience of dual/conflicting identities in having grown up in the Phil...