![]()

Part 1

Setting the Scene

![]()

1 Nature and Purpose of Corporate Financial Statements

1. Scope of Text

This is a study of the ‘history of accounting’ as a set of procedures or practices in contrast to ‘socio-historical accounting research’ which focusses on how accounting impacts on individuals, organizations and society in general (Napier 2009: 31–32). More specifically, this book is intended to provide an understanding of the procedures and practices which constitute corporate financial reporting in Britain at different points in time, and how and why those practices changed from one set of routines to another. Evidence of how things were done, and why they were done in those days in those ways, is provided by the contents of corporate archives, annual reports filed with the Registrar of Companies and the Share and Loans Department of the London Stock Exchange, articles in journals such as The Accountant, books on accounting and auditing, evidence presented to government fact-finding committees, especially the periodic investigations into the reform of company law, and the prior work of accounting historians.

The external financial reporting practices of British joint stock companies are worth knowing about given the widely held view that Britain (i) ‘pioneered modern financial reporting’ (Baskin 1988: 228), and (ii) played a primary role in the development of both capital markets and professional accountancy bodies (Parker 1986). The book’s corporate coverage starts with a chartered company which has been the subject of much prior research—the East India Company created in 1600—and continues through the heyday of the statutory trading companies founded to build Britain’s canals (commencing in the 1770s) and railways (commencing c.1829) to focus, principally, on the limited liability company created by the Joint Stock Companies Act (JSCA) 1844 and the Limited Liability Act 1855.

The story terminates when the corporate financial reporting practices of listed companies in Britain were placed under the jurisdiction of international accounting standards rather than national regulations. The downgrading of the role of UK accounting standards began in earnest when European Commission Regulation 1606/2002 (2002) came into effect. Article 4 required listed companies in member states of the European Union to use international accounting standards when preparing their consolidated financial statements for the financial year 2005 and onwards. This obligation was given statutory recognition in Britain through CA 2006 which, nevertheless, permitted all companies to publish their individual accounts in accordance with UK generally accepted accounting principles and non-listed parent companies to also publish consolidated accounts complying with that regime.1 Roughly a decade later saw the publication of Financial Reporting Standard 102 entitled The Financial Reporting Standard applicable in the UK and Republic of Ireland (Financial Reporting Council 2015). The new standard superseded all existing UK Statements of Standard Accounting Practice and Financial Reporting Standards and was based on the International Financial Reporting Standard for Small and Medium-Sized Companies. These episodes might be interpreted as signalling the effective end of British regulation of company financial reporting practices.

The accounting statements studied in this book are, principally, the balance sheet and the profit and loss account,2 i.e. the corporate financial statements (CFS) that continue to rank first and second among the four primary documents listed in the International Accounting Standards Board’s (IASB) discussion paper entitled A Review of the Conceptual Framework for Financial Reporting (IASB 2013: 137). The other two financial statements itemized in the discussion paper are the statement of cash flows and the statement of changes in equity. Coverage of the former is contained in chapter 17, while publication of the latter became standard practice in Britain only around the end-date of this book.

Sections 2–4 comprise a discussion of three issues which help to frame this history; they are followed by a discussion and analysis of the changing objectives, through time, of periodic financial statements.

2. Nature of Accounting Change

This book does not attempt to choose between starkly divergent ideas concerning the nature of accounting change. Some historians, who include disciples of Michel Foucault, believe that the past can best be explained in terms of historical discontinuities. At the other extreme are the so-called ‘traditional’ historians who are attracted to the idea that change occurs in an evolutionary manner. On some occasions, significant accounting innovation does occur rapidly, but whether such transformation amounts to an historical discontinuity that, of its nature, should be distinguished from the evolution of a new accounting practice, is a moot point. The present author takes the view that continuity and discontinuity are by and large ‘rhetorical devices’ which need not be seen as totally different historical processes (Mokyr 1999: 2). As one reviewer of a paper I authored observed: ‘the only valid question about discontinuity and evolution is whether accounting changes gradually or in lumps’. Or, as Waymire and Basu (2011: 208) express roughly the same idea: ‘accounting evolution [occurs] around crises as bursts of rapid change amidst periods of relative stasis consistent with punctuated equilibrium theory’.3

The Companies Act (CA) 1981 is an example of an event which brought about an abrupt change in corporate financial reporting practices. The new act obliged British companies to present their accounts in a standardized format whereas, previously, company directors were allowed a fair degree of latitude when deciding how to present information in CFS. The new practice, reflecting a different (continental) philosophy, was mandated by the Fourth European Directive on Company Law (1978), which Britain was obliged to implement having joined the European Economic Community (EEC) in 1973. Even in this case, however, things were already moving in that direction, in Britain, through the series of Statements of Standard Accounting Practice that date from 1970 (see chapter 18.4).

The view taken here, therefore, is that the history of CFS is consistent with the ‘gradualist’ school of thought which argues that changes which, at first sight, appear totally unrelated to what has gone before, when examined more closely often (but not always) turn out to be no more than significant landmarks in the transition from one state of affairs to another. The idea that change can be identified with a single causal factor has obvious appeal—if it were true, the chance of researchers finding answers to questions which puzzle them would be significantly increased—but this is rarely the way things happen within a social science such as accountancy.4 In essence, the history of CFS is therefore portrayed as a piecemeal process involving ‘continuity with change’; a term coined by Littleton and Zimmerman (1962: 245) and employed by myself and Trevor Boyns when writing A History of Management Accounting in Britain (Boyns and Edwards 2013). Lee Parker (2004: 8) sums up the nature of continuity with change in the following manner:

The focus is upon emergence of events from antecedent conditions such that change and continuity are both addressed. Change is initiated by the occurrence of events that establish new relationships in the world, while continuity is generated by their emergence from past conditions.

Accounting change is of course the consequence of actions taken by individuals, and sources for the expression of ideas about how published accounting statements are (or should be) prepared are numerous. Foremost among these are published textbooks, monographs and articles. The first of these has a long history: one can find evidence of new ideas about how accounting should be done, and how information should be presented in the profit and loss account and balance sheet, in the many texts on double entry bookkeeping published in Britain from the second half of the sixteenth century onwards (Edwards 2011). A journal-based literature began in 1874 when The Accountant was launched to provide a forum for the exchange of news and views about how the newly emerging profession of accountancy might improve its practices and raise its status.5 Illumination about how accounting was or should be done can also be found in submissions made to government-appointed committees charged with responsibility for amending and improving existing company law. A further venue comprises efforts made by professional bodies and other institutions to advance financial reporting practice by formulating new recommendations or standards for companies to follow. Finally, ideas expressed in the courts about the acceptability of prevailing practices are not overlooked.

In addition to the well-known, there is the army of ‘accounting thinkers’ whose identities remain a mystery. Anyone working in business who is involved with the accounting function can have ideas about how the informative value of accounting statements might be changed. But, as Baxter pointed out, there will probably be no public record of the contributions which they make. Reflecting on the growing impact of regulations on the form and content of CFS, in 1981, he offered the following description of the prior process of accounting change:

Hitherto, accounting has been pushed forward by forces internal to firms. Obscure people, bent on improving their existing methods or meeting new needs, have continually made minor experiments. If an experiment failed, it was abandoned and forgotten; if it was a success, it was kept and in time copied in other firms. Accounting has thus grown by small steps, and is the creation of countless anonymous innovators.

(Baxter 1981a: 6)

Although Baxter’s assessment is open to criticism as representing a naïve belief in accounting Darwinism, the broad idea has much to commend it. Businessmen and women are at least as much preoccupied with the image portrayed by published financial reports as are accountants. Perhaps more so. Often justly pilloried for engaging in schemes of unparalleled deception, it is not difficult to believe that they have also been the instigators of innumerable innovations intended to communicate more effectively corporate financial progress and position.

The scope and limitations of agency theory as a framework to help us understand the history of CFS is next considered.

3. Agency Theory

Following Ó hÓgartaigh (2009: 163; see also Sidebotham 1970: Ch. 2), and others, this book draws upon agency theory as ‘a useful lens through which to observe the contours of change in financial accounting practice’. An unproblematic version of agency theory postulates that ‘the demands of outside investors (or other stakeholders) tend to determine the form and content of financial statements’ (McCartney and Arnold 2012: 1291). In this version, managers (as agents) voluntarily respond to investors’ (as principals) demands for better accountability to raise finance at minimum cost.

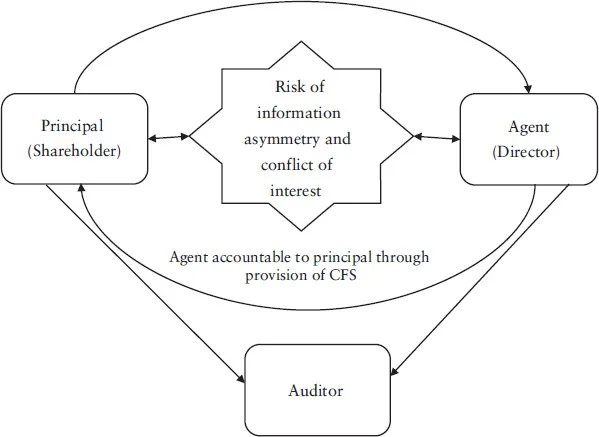

Writing in the late 1970s, Watts and Zimmerman drew on accounting’s known past to theorize the history of financial reporting and auditing processes from an agency perspective (Watts 1977; Watts and Zimmerman 1979, 1986). For them, the rise of external financial reporting was a market-driven development, i.e. shareholders demanded reliable information and directors responded by arranging for an independent audit to make credible the financial statements whose content they control. Figure 1.1 depicts the agency relationship between shareholders and directors that creates the demand for an external audit to counter risks of information asymmetry and conflict of interest. Based on this and similar work (e.g. Leftwich 1983; Taylor and Turley 1986; Rahman 1992), a substantial literature portrays market forces as the most efficient mechanism for ensuring that directors keep shareholders and creditors properly informed. Criticisms of state intervention include the belief that it is not cost effective and that it creates a demand for accounting theories (excuses) designed to justify the self-interest of particular pressure groups.

Figure 1.1 Relationships between shareholders, directors and auditors

3.1. Lack of Goal Congruence

As agency theory acknowledges, however, the usefulness of CFS depends on the willingness of corporate management to comply with best accounting practice. The provision of financial information by corporate entities is therefore studied within a principal and agent relationship where a lack of goal congruence is recognized as having significant implications for the quality of CFS.

Provided a company is doing well there should be no problem. The directors will seek to publish CFS that display a true and fair view of corporate performance, and such data will be welcomed by shareholders and other user groups. However, if results are poor, conflict between the priorities of the directors and the shareholders might come into play. One might imagine that the shareholders will still wish to know the truth whereas there will be a temptation for the directors not to ‘tell it as it is’ (Clarke et al. 2013: 35). Misreporting might occur because, otherwise, investors will be disappointed, the company’s share price will fall, the directors’ performance may become the subject of press criticism, management remuneration packages will be subjected to greater scrutiny and the threat of a takeover bid might increase. These are not the only possible consequences of a company publishing CFS which do not match market expectations, but they are enough to show that management has a vested interest in publishing healthy results.

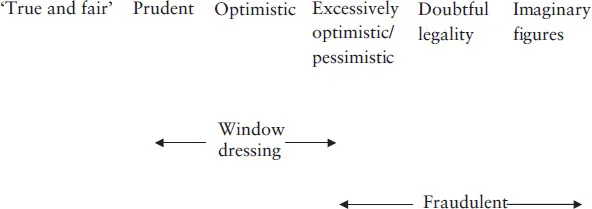

The falsification of CFS, to a greater or lesser extent, is the subject of Figure 1.2. The left-hand side of a range of possibilities depicts management doing its best to publish CFS which faithfully represent an entity’s performance and position, i.e. the CFS comply with what are today described as the underlying assumption and qualitative characteristics of published accounting statements. Progressing across the diagram there exist a range of possibilities. The accounts may be the subject of relatively minor distortion. That is, management might make a somewhat prudent assessment of asset values (and therefore profit) just ‘to be on the safe side’. Or it might be a little optimistic about the future value to be derived from expenditure incurred, resulting in the overstatement of asset values and profit as happened when the management of Associated Electrical Industries attempted to resist a takeover bid from the General Electric Company in 1967 (see chapter 18.3) As one moves further to the right in Figure 1.2, the problem gets worse (see the Royal Mail Case, chapter 9.4) until management literally plucks figures out of the air for inclusion in CFS published for external use. So, whereas towards the left side of the diagram, management might be described as engaging in ‘window dressing’, towards the right-hand side management increasingly veers towards the kind of fraudulent reporting revealed in the case of the City of Glasgow Bank 1878 (see chapter 9.3) and, more recently and most famously, associated with the collapse of the US Enron Corporation in 2001.

Figure 1.2 Management manipulation of CFS—range of possibilities

The next sub-section develops further the notion of CFS as socially constructed phenomena.

3.2. CFS as a Social Construction

The previous sub-section has alerted readers to the fact that management is not always inclined to make every effort to ensure that CFS faithfully represent a company’s performance. But the problem of ensuring that the published accounts are fit for the purpose has a further important dimension.

Accounting has often been portrayed as a value-free, neutral function (Peasnell 1978; Chua 1986) with accounting practices ‘pragmatically derived from the needs of accountable organisations or individuals’ (Funnell 1990: 319). An alternative view is t...