![]()

Chapter 1

Surfing and sustainability

Critical connections

Introductions are often the last thing to be written in a book; they certainly are in mine. It is only after you have finished everything else and got to the end that you can come back to the beginning to introduce what’s coming next. This has been particularly the case with this book, which has spanned research conducted over five years and a lifetime of surfing – and what feels like a lifetime of being involved in different aspects of sustainable development. These final words I write sat on the train from Plymouth to London, heading to the Surfers Against Sewage Protect Our Waves All Parliamentary Group reception in the Palace of Westminster, Churchill room. And this is symbolic of the expanse of the journey that I have taken through the research landscape that stretches across the globe, from beach to bar to the Houses of Parliament, and everything else in between. It has been a profound joy as I have at once been able to indulge my own passion and give back to an activity that has given so much to me. But it has also come at a cost, with an enduring prejudice that nothing relating to surfing can be a legitimate academic activity. My hope is that this book and the books that have preceded it add weight to the legitimacy as well as transcend the surfing world to make a valuable an enduring contribution to both theory and practice. As you will see, the focus of this book is the relationship between surfing and sustainability. This is a relationship that is not complete, nor is it definitive; indeed it is highly selective and subjective. And as I have explored the research question, ‘what is the relationship between surfing and sustainability?’, it has emerged as a constellation of interconnected themes and peoples that has changed and morphed over time. This introductory chapter will achieve three goals. First, it will introduce the principle terms of this research, surfing and sustainability; second, it will discuss the relationship between the two; and third, it will outline the structure of this book.

Sustainable development

The idea of a sustainable development and sustainability has proliferated exponentially over the past five decades. And while sustainable development and sustainability are not necessarily synonymous, the term sustainability in the context of this book has its origins in the concept of sustainable development. First, I will provide a brief timeline for the concept that will explore some of the main publications and events that have contributed to the rise of sustainable development. Second, I will introduce the concept of sustainable development, emphasising it as a contested and ambiguous concept meaning many different things to different groups and organisations. Third, there will be a discussion on emerging perspectives on sustainability and, finally, I will discuss sustainability from a transitions perspective.

Multiple reports and assessments in the past few years point to the following. The global population now stands at 7.4 billion, global greenhouse gas emissions are increasing, impacting on multiple facts of anthropogenic climate change. Biodiversity loss is continuing to accelerate, social inequality is growing and economic instability threatens social and political integrity on a global basis (UNEP 2012; UNDP 2015).

At all levels of our biosphere, land, sea and air, there is increasing evidence of pollution, acidification of the oceans, loss of fisheries and habitats, deforestation, desertification and rises in CO2 levels contributing to climate change. Many of us recognise that our current developmental pathway is unsustainable. As a concept, sustainable development can be charted through a number of key publications, although there are other factors and other key events that have contributed to the evolution of sustainable development over the last half a century. It is largely held that Rachel Carson’s book, Silent Spring (1962), represents the emergence of what we understand as environmentalism today. It brought together research on toxicology, ecology and epidiology to suggest that agricultural pesticides were building to catastrophic levels. In 1968 Paul Ehrlich’s The Population Bomb warned that a rapid increase in population size would have a negative effect on the natural environment because we would exceed the carrying capacity of the planet. In 1972, the Club of Rome published their controversial Limits to Growth report, which painted a very dire picture for the future of the planet if humanity continued along its present course of development (Meadows 1972). The cumulative effect of increased awareness of environmental degradation prompted the United Nations Conference on the Human Environment (UNCHE) at Stockholm, also in 1972. It was in the wake of the UNCHE that the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) was created and it was at this point that sustainable development, as a concept, began to gain currency in political and social dialogue. The often quoted definition of sustainable development was coined in the report of the World Commission for Environment and Development (WCED), Our Common Future, in 1987. This is more commonly known as the Brundtland report, named after the chair of the commission Gro Harlem Brundtland, the then Prime Minister of Norway. Here, sustainable development is: ‘Development that meets the needs of present populations without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs’ (WCED 1987: 3).

This emphasises intergenerational equity and considers what legacy we leave our children and grandchildren. Perhaps the most well-known conference was the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development, held in Rio, in 1992. This was more popularly known as the Earth Summit and was the largest environmental conference ever held, with more than 30,000 people and over 100 heads of state in attendance. While the success of this event is disputed, there were a number of important outcomes. These include the Convention on Biological Diversity, the Framework Convention on Climate Change, Principles for Forest Management, the Rio Declaration on Environment and Development and Agenda 21. Agenda 21 remains the most comprehensive document relating to sustainable development ever produced. It presents 21 principles of sustainable development and discusses them in 40 chapters that translate the principles into action. Far from being a top–down approach, Agenda 21 emphasises the importance of community-based approaches, or bottom–up participatory action. In 2002 the World Summit on Sustainable Development (WSSD) was held in Johannesburg. In 2012, the United Nations staged the Summit on Sustainable Development (UNSSD), or ‘Rio + 20’. An important outcome of the UNSSD was to begin the process of designing the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Coming into being in 2015, there are 17 SDGs, each with a number of targets totalling 169 (Blewit 2015; Gupta and Vegelin 2016; Linner and Selin 2013).

With the above in mind and in spite of goals and targets, debates surrounding whether a sustainable development is actually achievable are ongoing. Some argue that it is too late and that we are beyond the tipping point, exponential population growth, rampant resource depletion combined with no real political will or scientific know-how to avoid a global catastrophe. Others argue that technology will come to the rescue and that we will inevitably respond to the problems we have created through, for example, clean renewable energy sources, advancements in material technologies or the ability to recycle and reuse existing materials. This has been labelled as weak sustainable development as it does not suggest a wholesale reorganisation of our social and political systems. Yet others argue that a strong form of sustainable development is necessary that involves a radical reordering of the current systems of production and consumption upon which we all depend because a reliance on technology is not only insufficient to address current problems but also that technology is the reason that we are on an unsustainable pathway. Throughout this book we will see various incarnations of these perspectives in the narratives of those that have participated in this research as well as the tangible impacts of those making a difference on the ground. Moreover, this tension is explicitly addressed in the theoretical discussion in Chapter 3 and, along with the diverse perspectives on sustainable development, the concept also provokes a significant amount of criticism.

Criticisms of sustainable development can begin by re-examining the Brundtland definition: ‘meeting the needs of current generations without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.’ Meeting the needs of present and future populations is a hugely subjective idea; what is a necessity for one group is unlikely to be a necessity to another. And who is responsible for deciding what those needs are and how those needs are met? How can we accurately gauge what the needs for future generations might be with so many variables interfering with our ability to model and forecast possible future scenarios? From the outset, sustainable development encompasses a number of challenges. As a concept, it has been described as an oxymoron, that no development by its very nature can be sustainable. Sustainability means so many different things to different people that ultimately it is ineffective as a concept to drive policy, implement programmes, create legislation and generally promote solutions. Perhaps the most serious accusation levelled against sustainable development is that it is a term that does nothing more than legitimise existing modes or production and consumption. This has often been termed ‘green wash’: sustainable development is used to make whoever is using it appear to be doing the right thing. And in different contexts all of these criticisms are supported. With this in mind there are two reasons why sustainable development has become one of the twenty-first century’s most pervasive concepts. First, sustainable development offers a constructive ambiguity (Borne 2010). In other words, the concept is so vague that it can mean all things to all people and as such provides a focal point for different groups and ideologies to come together, learn, share and understand. Second, there is overwhelming consensus that the pathway that humanity is currently on is quite simply unsustainable and we have to do something about it.

Sustainable development evolutions

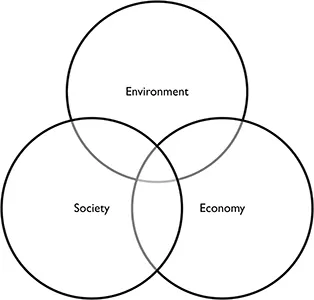

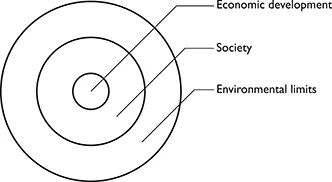

The previous discussion provides a brief introduction to sustainable development and some of the issues that are related to it. The following will explore how sustainable development is understood, building up a progressively more complex picture. The starting point for this is the relationship between the three dimensions of human interaction with the environment – namely, society, environment and economy. This has been variously presented; the Venn diagram and the Russian doll are the simplest and clearest representations of this.

The Venn diagram model (Figure 1.1) shows us that sustainable development exists at the intersection between the environment, economy and society. In the past two decades, however, there has been a move to explore sustainable development from a more sophisticated perspective.

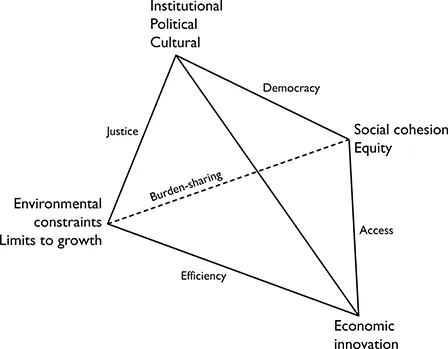

The Russian doll model (Figure 1.2) suggests that all economic activity should lead to social progress and that both social and environmental concerns must be considered within environmental limits. With this in mind, both the Venn diagram and the Russian doll models remain simplistic and tell us very little about the complexity inherent within sustainable development. The three-dimensional model shown in Figure 1.3 attempts to elaborate on the previous models, including more dimensions and issues such as justice, democracy and access. And while these frameworks of sustainable development are useful and start us off on the journey to a better understanding of the interaction between humanity and our environment, they remain limited. They are limited because, as we explore ways of achieving a sustainable future, it is recognised that the problems faced by the world today, and the risks that come with them, are themselves complex, uncertain and non-linear, crossing disciplinary boundaries, sectors and nations.

Figure 1.1 The three pillars of sustainable development.

Figure 1.2 The Russian doll.

Figure 1.3 Three-dimensional model.

With this in mind, sustainable development, as a way of viewing the world, must be able to mirror the complexity of humanity’s interaction with the environment if it is to be in any way effective. And to this end a paradigm shift has emerged around sustainability that has impacted how we create and use knowledge within society. And this has been very aptly termed sustainability science (Kates 2011; Miller et al. 2014) and defined as an emerging field of research dealing with the interactions between natural and social systems and with how those interactions affect the challenge of sustainability (Harris 2007). Sustainability science emphasises notions of reflexivity, complexity, uncertainty and systems theory (Norberg and Cumming 2008).

Systems theory is an interdisciplinary field of science that studies the nature of complex systems in society, nature and technology. At its core, it provides a framework for analysing a group of interrelated components that influence each other, whether these are a sector, city, organism or an entire society. This can be said to be beneficial in two ways. It is a useful theoretical approach for understanding the complex interconnectivity of issues that relate to achieving sustainable development, but also, it emphasises on-the-ground, practical solutions and provides a number of methods for doing so. This can include developing models and scenarios, using focus groups and interviews. It emphasises participation and the inclusion of multiple stakeholders and multiple forms of knowledge – knowledge that can range from the scientific to the local lay and indigenous knowledges. There is also an increasing body of work, both theoretical and practical, that focuses on transition dynamics towards sustainable development. This draws on the aforementioned perspectives and will be further explored in Chapter 3 (Grin and Schot 2010). A transition is a fundamental change in structure, culture and practice. Structure can include physical infrastructure, econ...