There are many types and forms of opposition in modern societies and the day-to-day usage of the word encompasses a wide “variety of developments” (Blondel, 1997, p. 462). 1 However, as opposition has evolved, it has become mainly associated with the institutionalisation of political conflict (Rokkan, 1970) together with the rise of modern democracy. The present volume, therefore, focuses on the specific form of opposition carried out by political parties within parliament, that is, parliamentary opposition.

The modern concept of parliamentary opposition has evolved alongside the development and institutionalisation of inter-party conflicts in the parliamentary framework and it has been applied in diverse forms in different countries over the years. Indeed, the meaning attached to it varies in line with the countries’ specific trends of conflict and cooperation, which may in turn be affected by a large number of factors. The major purpose of this comparative book is to shed light on how parliamentary opposition behaves in each of the countries considered and what affects this behaviour. The aim is also to determine whether variation continues to be the main characteristic of this political actor both within and among countries, as formerly argued (Dahl, 1966), or whether a common trend can be identified in (some of) the countries under analysis.

This process has three potential outcomes. First, we may continue to find the extreme variation in opposition behaviour identified in Dahl’s classic volume on opposition in 1966. To some extent, this is to be expected as the nature and management of political conflicts remain rooted in a wide range of politics and institutions (Sartori, 1966; Helms, 2008). Furthermore, since the publication of Dahl’s volume, this variation has been fostered by the formation of many new democracies. Second, we might also find some general shared trends. The overarching umbrella of the European Union has inevitably influenced the behaviour of both governments and oppositions. In addition, parliamentary opportunity structures have changed in many European countries along the same lines (von Beyme, 1987; Fish, 2005) and we believe this evolution has played a role in (re)shaping the opposition’s conduct in recent years. Third and finally, there have been new developments in many European countries, which might have responded to these challenges in various ways. In particular, it is likely that the transformation of the party context – notably the success of new party families (Mair, 1997, 2011; Bardi et al., 2014) – and the economic crisis (Bosco and Verney, 2012; Moury and De Giorgi, 2015) have had an impact on the opposition’s behaviour. It remains to be seen whether (and how) these new developments have led to more varied opposition’s conduct or pushed general patterns to evolve.

Parliamentary opposition is not a unitary force, as it is always formed by numerous actors, that is, political parties. Thus, to understand the role and functions of parliamentary opposition, it is paramount to examine how individual parties relate with the government and how they interact with each other in this process. Their complex connections will be the primary focus of this book.

Parliamentary opposition is defined herein as a political actor composed of one or several party groups that oppose the governing forces; its aim is to exercise control and appear in parliament as a challenger that provides an alternative to the government in political and policy terms. This book analyses the three main activities undertaken by opposition parties in parliament to this end: voting on legislation, proposing legislation and scrutinising the government. The following sections briefly describe the distinctions in the way the opposition exercises its prerogatives in parliament vis-à-vis several systemic and non-systemic variables. Hypotheses will be formulated about their impact in three broad areas in particular: the party context, the institutional setting in which parties interact and some specific external constraints, namely the onset of the global financial crisis and the EU’s increasing intervention in this context – leading to novelties, variation, and general patterns in the opposition behaviour.

The party context

The rich academic literature on party developments presents an array of arguments about partisan features that might impact the behaviour/activities of the opposition in parliament. In addition to streamlining these arguments below, we identify their potential effect on the opposition’s activity in three broad categories: the nature of parties, the nature of the party system and the nature of the opposition itself.

The party perspective

The two major approaches used to explain party behaviour are equally applicable to the behaviour of opposition parties. Whereas the first argues that parties are strategic actors and their goals determine their conduct, the second claims that parties’ behaviour is a result of structural attributes. According to the first approach, the behaviour of parties on both the opposition and government benches in parliament is driven by electoral, position-seeking and policy-seeking goals because their overriding objective is to gain votes and positions and implement policies (Müller and Strøm, 1999; Andeweg and Nijzink, 1995; Pedersen, 2012). Behind a vote for or against a policy related government bill, numerous electoral considerations or prospective office-related expectations are played out (Brauninger and Debus, 2009) even in opposition. However, these strategic motivations will depend on party attributes as “some parties are better suited for strategic action than others” (Rovny, 2015, p. 916). For example, a major party with many diverse and often contradictory interests will exercise the role of opposition differently from a minor party, which groups just a few interests in a particularly well-defined manner. Variation in the parties’ features remains a major explanatory source of opposition behaviour (Pedersen, 2012).

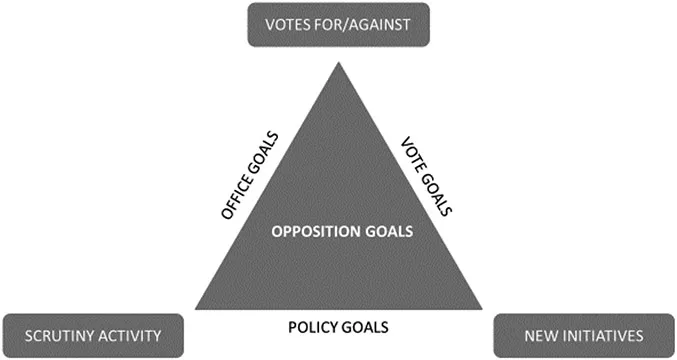

One of the factors that affects behaviour in opposition is the party’s political history – for example, its tradition and parliamentary experience (Steinack, 2011). The context in which a party is formed, notably in new democracies, might well matter. The behavioural messages sent by successor parties will differ from those of new parties: the former might be less confrontational to prove their cooperation potential, while the latter might adopt more confrontational strategies to build a genuinely new profile and identity. Party novelty, or more broadly, party age and experience will be decisive in these matters. Additionally, even a simple organisational feature like party size can be expected to result in different behaviours: small parties concentrate on scrutiny activity rather than propose policy initiatives that require considerable resources. As Figure 1.1 shows, it is essential to consider (and test) the combination of a party’s strategic aims and structural attributes when explaining opposition party behaviour in the following chapters.

Figure 1.1 The opposition parties’ goals and strategies

The three aspects of the opposition’s parliamentary behaviour analysed herein are expected to serve the parties’ goals in different ways. Voting for or against government initiatives is largely tied to office-seeking and vote-seeking goals. This will be the most sensitive parliamentary activity for the opposition parties, as it allows them to express their political stances more clearly: it shows whether or not they are relentless challengers of the government, and sends a clear message to their potential constituency. On these grounds, we expect to find the most clear-cut behavioural patterns of opposition in this activity. The opposition’s scrutiny activity is linked primarily to office and policy goals and has a different force: an office related confidence motion or a “simple” parliamentary question will serve different party objectives. Moreover, scrutiny will depend on the diverse intra-parliamentary regulations of each country. Thus, it can be rightly assumed that the opposition’s behaviour will vary greatly in this context and possible patterns will not be so clearly defined. New legislative initiatives of the opposition parties will be motivated mainly by policy goals, as occasionally the desire of attracting voters’ attention can play a role in this. Parliament is not the terrain for the opposition to achieve its own policy results, not to speak of how costly policy initiative is overall; we therefore expect more modest activity in this context than in the other two.

The party system perspective

Following the former line of thought, opposition party behaviour will depend on the nature of the party system as well as on how parties connect and how their political space is organised.

When writing about the structure of the party system, Duverger (1951) stated that multi-partism and bipartism gave rise to different opposition patterns (p. 414), although this is more than a simple numerical relationship. The following are of paramount importance for the opposition’s behaviour: the level of polarisation of the party system, i.e. higher polarisation might trigger a generally higher level of conflict in terms of action; and whether there is a major party that is difficult to challenge or alternatively several small/medium-size parties with more opportunities to negotiate. This generates different behavioural considerations from the opposition’s perspective.

The party system structure matters even within the opposition area. When the opposition party system is polarised, parties can be expected to follow more individualistic strategies, and this might also be the case when the opposition is fragmented. The opposition party system will consequently affect the parties’ goals and their strategy to achieve them: vote, office and policy considerations will appear in a different light depending on the specific opposition context.

The opposition perspective

The opposition’s government potential or vocation is another fundamental feature affecting its conduct. This idea was first developed by Giovanni Sartori (1966). “An opposition which knows that it may be called to ‘respond’, i.e. which is oriented towards governing and has a reasonable chance to govern […] is likely to behave responsibly, in a restrained and realistic fashion. On the other hand, a ‘permanent opposition’ which (…) knows it will not be called on to respond, is likely to take the path of ‘irresponsible opposition’ ” (ibid., p. 35). Although Sartori was thinking mainly of the Italian case and its polarised multiparty system, the distinction between responsible and irresponsible opposition is still expected to be relevant. 2

According to the theory of responsible party government, parties should be both responsive to their electorate and responsible for what they do in government. 3 These two concepts have become increasingly incompatible in the last decade (Bardi et al., 2014; Freire et al., 2014; Rose, 2014); indeed, some scholars have started to speak of a “growing divide” in European party systems between parties that govern but are no longer able to represent, and parties that claim to represent but do not govern. The latter constitute what Mair (2011) calls the “new opposition”: they (almost) never hold any government responsibility and can consequently maintain a high level of responsiveness to their electorate; they are usually characterised by a strong populist rhetoric although they cannot be defined as “anti-system” in Sartori’s use of the term (1976).

However, as Kriesi states, such a sharp division of labour between these two types of party seems too static (2014, p. 368). The so-called new opposition parties may, in fact, enter the government in a subsequent election and the division of labour envisaged by Mair may therefore be transitory rather than permanent. Indeed, some extreme right and populist right parties aim to acquire government responsibility, and some have actually managed to do so (Akkerman et al., 2016; Ágh, 2016; Enyedi, 2016; Minkenberg, 2013). In Eastern and Central Europe (ECE), new parties – frequently with a radical populist agenda – took a position in government immediately after entering parliament without spending any time on the opposition benches. Thus, we can assume that their responsiveness versus responsibility credentials are blurred (Grotz and Weber, 2016).

Nonetheless, permanent opposition parties do exist in most European democracies and we claim that the temporary versus permanent opposition status would significantly affect the parties’ choices in parliament. With this distinction in mind, we identify two major goals for opposition parties: leaving opposition, that is, getting into government as soon as possible; and exploiting opposition, that is, trying to take advantage of the opposition status. These goals might give rise to two very different behavioural strategies depending on the party’s opposition status. A temporary opposition party – i.e. one that has been alternating in power – would consider getting into government a feasible goal. Thus, we expect these opposition parties to be more cooperative in terms of voting behaviour and more passive in other parliamentary activity, notably legislative initiative and scrutiny activity. As Sartori said, these parties know they will be held accountable for their actions, but, we add, they could soon be in the government’s position. They therefore usually keep a more moderate profile in their confrontation with the executive, except in the presence of relevant programmatic issues or media attention. As for the second goal, we expect parties, notably those permanently in opposition, to act in a more adversarial way as well as to be more active; successful parliamentary activity and the actions of opposition parties outside of parliament increase their electoral opportunities and chances of getting into parliament again. Increased confrontation often gives more visibility to the actors involved, so they can exploit their opposition status in this way.

Under favourable ...