![]()

Part 1

Relations

![]()

1

On the ontological scheme of Beyond Nature and Culture1

Marshall Sahlins

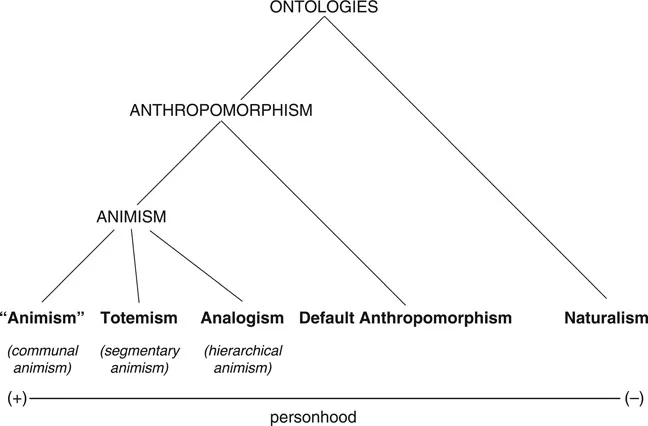

Not to quibble: One can accept the empirical reality of Philippe Descola’s fourfold differentiation of animism, totemism, analogism, and naturalism. Anyone not persuaded by Beyond Nature and Culture (Descola 2013) would be hard put to maintain such skepticism if they had seen the exposition of images of these systems mounted by Philippe at Quai Branly (Descola 2010). My reading of the ethnography, however, is that they are not equipollent ontologies, inasmuch as humanity is the common ground of being in totemism and analogism as it is in animism proper. Whether one takes Philippe’s determination of animism as “the attribution by humans to nonhumans of an interiority identical to one’s own” (2013: 129), or something like Graham Harvey’s “animists are people who recognize that the world is full of persons, only some of whom are human, and life is always lived in relationship with others” (2006: xi), these notions of the subjective personhood of nonhuman beings apply as well to the archetypal totemism of Aboriginal Australians and the exemplary analogism of native Hawaiians as they do to the paradigmatic animism of Amazonia. Rather than radically distinct ontologies, here are so many different organizations of the same animic principles. Classical animism is a communal form, in the sense that all human individuals share essentially the same kinds of relationships to all nonhuman persons. Totemism is segmentary animism, in the sense that different nonhuman persons, as species-beings, are substantively identified with different human collectives, such as lineages and clans. (Apologies to Marx for this adaptation of “species-being.”) Analogism is hierarchical animism, in the sense that the differentiated plenitude of what there is encompassed in the being of cosmocratic god-persons and manifests as so many instantiations of the anthropomorphic deity.

Sharing the same animic ground, each of these predominant types, moreover, may include elements of the others as subdominant forms: The way that Amerindian communal animism also knows a hierarchical aspect insofar as the spirit masters of game animals rule the individuals of their species; as likewise in Australian totemism the Dreamtime ancestors encompass their animal and human descendants. For its part, the analogism or hierarchical animism of Hawaiians includes a totemic element in the form of ancestors incarnated in natural species thereupon distinctively associated with their descendants. These are not ad hoc historical mixtures of ontologies, however, but so many expressions of the same animic subjectivity, apparently depending on the context in which the nonhuman persons figure: whether mythical, ritual, magical, technical, or shamanic; collective or individual; dreamed or experienced; and so forth.

Moreover, the several animic orders are themselves marked forms of a more generic anthropomorphism: a disposition for personification which, as Eduardo Viveiros de Castro observes, is also our own default way of talking about institutions, nations, ships, and many other things, absent a naturalistic take on them (personal communication). Granted the attributes of personhood, such as perspectivism, peter out through this series, becoming something of an ontology reduced to an epistemology in the default anthropomorphism, and presumably disappearing altogether in scientific naturalism. Even so, we know a physics whose subject matter is “a world of ‘bodies’ that behave according to ‘laws’” – to cite one of Eduardo’s throw-away pearls (2012: 118n) – let alone banks that screw people, political parties that war on women, corporations that as legal persons have freedom of speech, or universities that trade their reputations for money. I won’t even talk about the human nature of our pets, let alone our animal fables, since I have only about eight pages left to describe the universe: an alternate universe to Philippe’s fourfold table, as shown in the accompanying tree diagram (Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 Ontological relationships

Discussing the mythology of totemism in South Arnhem Land, Australia, Philippe notes a certain resemblance to many Amazonian narratives. “In both cases, the beings whose adventures are recounted are certainly a mixture of humans and nonhumans living within a regime that is already cultural and social through and through” (2013: 163). Beside such mixed beings of The Dreaming, moreover, there are even more purely animic forms, such as the sun, which, the Aranda tell in myth, came to Earth in the form of a woman and a member of a certain section. Accordingly, the sun “is regarded as having a definite relationship to various individuals, just as a human being of that class has” (Spencer and Gillen [1904] 1969: 624). It seems, then, that the facts are not at issue so much as the conceptual value one would attribute to them.

Despite what is to all appearances a common animic ontology, Philippe argues that Australian totemism offers a “striking contrast” to Amazonian animism in three related ways – which, I would argue, merely show that totemism is the animism of segmentary collectives. First, the Australian totems are generally species-beings, primarily animal and plant species; hence realist types of which individual members are tokens, by contrast to the interpersonal relationships of humans and nonhumans in Amazonian animism. In this classificatory regard, the totemic species are coordinate with their human affiliates, likewise organized in collective entities with a class identity such as clans, moieties, sections, and the like. Because the human and nonhuman subjects are collective, however, and individuals interact as instances of them, this should not make their relationship any less animic. Second, whereas in Amazonian animism, human and nonhuman persons develop out of common human origins, the Australian totemic groups have separate and distinct beginnings, being the sui generis creations of their independent Dreamtime ancestors – which is simply the logical-cum-etiological corollary of their status as collectives of different kinds. This structural differentiation also applies to the third contrast: the substantive identity of humans with their respective totems – a physical and subjective continuity in Philippe’s system – explicitly conceived in terms of the kinship or mutuality of being of the human group and totemic species, by contrast to the different physical identities (if similar interiorities) of humans and others in animist regimes. In sum, totemism is a segmentary animism of differentiated collectives composed of conspecific human and nonhuman subjects. (Perhaps it goes without saying that such is not exactly the animism of Latourian collectives that include inorganic “agents” who are somehow equivalent to intentional and cultural humans.)

If indeed the totemic beings of Australian Aboriginals live in “a regime that is already cultural and social through and through,” then the resemblances of this totemism to the prototypical animism do not end there. Philippe’s characterization of the conspecific identity of humans and their totem species as “hybridity,” a mixture of human and totem, rather leaves hanging the question of in just what way, in terms of interiority and physicality, the human aspect of actual kangaroos or parrots comes in. We know that humans in totemic systems may have purported resemblances to their animal fellows in the way of birthmarks or behavioral dispositions, but what about the existing animals? In what respects are they human? From my own brief perusals of the ethnography I cannot answer that interesting question – unless the two or three examples of perspectivism in Strehlow’s Aranda Traditions ([1947] 1968: 37, 140) represent something more than a subdominant version of animism that is virtually as good as it gets in Amazonia. The narrative about the red kangaroos and their father’s sisters, the mulga parrots, for instance: parrots whose calls during the day warn their kangaroo nephews of the approach of human hunters. During the night in the netherworld, however, the animals assume human form themselves and interact in cultural terms. Indeed the tradition ironically doubles down on the cultural aspect, as the mulga aunt is equipped with a hide bag made of kangaroo skin in which she as a human woman brings water to her brother’s son, the kangaroo in the shape of a man. Moreover, the narrative concludes with an incident of pure perspectivism when the next morning the hunter-persons perceive that bag as the place on the ground where the kangaroos licked for water. What humans perceive as a natural soak frequented by kangaroos, the animals know as waterbags manufactured from kangaroo hide. Taken with the sometime appearance of the sun and moon as female and male humans, this totemism has the essentials of an all-around animism.

A caveat: I am not claiming that totemic species are merely the symbolic reflexes of social groups that in some sense preexist them as real-empirical models – as in the Durkheimian theory of “collective representations” that has reigned for too long in our social sciences. As the diacritic principle of social differentiation, that which constitutes the identity and nature of the human group, totemism is an integral condition of its formation. Rather than a post hoc reflection of a social fact, the totemic identity may well be present from the creation, marking the emergence of the group itself; or else, as an add-on secondary totem, it figures instrumentally in the group’s interested differentiation from others. The totem is an enduring mark of a politics of difference, a schismogenic process, which helps explain why the array of totemic identities among a given people is often wildly unsystematic. Lévi-Strauss’s (1963) notions of totemism as a natural taxonomy of social entities notwithstanding, ethnographic reports of totemism generally have all the classificatory logic of the scheme of animals in the apocryphal Chinese encyclopedia described by Borges (1964) that included embalmed ones, suckling pigs, and animals that at a distance resemble flies. But then, as Lévi-Strauss protested in The Savage Mind (1966), structuralism is only a science of the superstructures: practice he ceded to Marx. Even so, he did acknowledge that conspecific relations between humans and their totems could be integral to the phenomenon, and that historically the creation of totemic entities could be practically opportunistic even as it is logically motivated – witness Whitemen as an Australian totem.

Precisely in this connection, in his excellent ethnography of the Manambu of the Middle Sepik, Simon Harrison (1990) describes a competitive process of totemic formation in which the roster of totems is characteristically expanded by political moves that appropriate beings from more powerful cultural realms beyond it. This sort of homage to the powers of alterity – and the alterity of powers – is well known to the Sepik peoples, and it involves them in exchanges of a great variety of ritual, material, and monetary items. So when a certain Manambu subclan claimed the clothing of colonial officials as one of its totems – on the ground that its honorific address form was homonymous with the term for the European-introduced laplap – it was trumped by a rival subclan who claimed the Queen herself for their totem – on the ground that the Australian government crest on school exercise books depicted one of its own traditional totems, the cassowary (76–77). (Actually, it was an emu, the Australian colonials’ own native totem.) The analogic moves here, as we shall see, are typical tactics of hierarchical animism (aka analogism), and they are likewise employed by Manambu to form a large series of natural and cultural species under the domination of totemic ancestors: that is, as visible instantiations of them.

But then, the Manambu, for all their totemism, also know the essentials of Amazonian animism, including perspectivism – even as Harrison more than once likens Manambu totemism to the Aranda’s (ibid: 7, 51). Like the Aranda, Manambu subclan members are kinsmen and conspecifics of their totems by virtue of their common creation by the totemic ancestors. Also rather like Aranda, then, is the (literal) organic solidarity of the Manambu totemic system: The consubstantiality of people and their totems is such that in allowing one another the use of their totemic resources, “they nourish each other with their own flesh” (46). The totemic ancestors are men and women themselves, but Manambu cannot see them as such: They do not show themselves to living people in their true forms. “They are only visible as animal and plant species, as rivers, mountains, ritual sacra, and so on: that is, only in their outward, transfigured forms.” For beside the visible world of humans, there is a concealed world in which things exist “in their real forms, which are human forms” (ibid). As it was explained to Harrison, in words that could have been spoken by an Amazonian Arawete, down to the matter of bodily differences in perception: “You realize that this tree isn’t really a tree. It is actually a man, but you and I can’t see him because we are only living people. Our eyes aren’t clear. We are not able to see things as they really are” (ibid). Or again: “Suppose a man fells his breadfruit trees to take their fruits. The fathers [the totemic ancestors] … would become angry with him for destroying his trees, saying to themselves, those are our very bones he has cut. Or suppose the man harvests the immature fruits…. The fathers would see this and be angry, saying to themselves, why has he damaged the tree? It is not just a tree, it is a man. It has a name, and a father, a mother, and a mother’s brother, and the fruits are his children” (48).

Everything considered, here too is a dominant totemism with all the elements of classical animism and hierarchical analogism – all on the one ontological ground of humanity. Indeed, Harrison describes Manambu cosmology as “a systematic animism, a thorough-going socialisation or human-isation of the conceived elements of the world. It projects notions of human identity and agency on animals, plants, ritual objects, and all the rest: They share kinship with human beings, have names, belong to subclans, marry and so forth” (ibid: 58). “Projection” may not accurately describe a system in which the totemic ancestors and living men and women are each other’s namesakes, and the same names are the names of mountains, rivers, plants, animals, and other things “because these things are in themselves in reality men and women” (56).

The Manambu are not unique in such respects among neighboring peoples, as the regional extension of clanic relations has been known to facilitate the extraordinary trading practices for which the Sepik area is famous. But there is not space to speak of this, nor of the animic parallels in Africa, North America, and elsewhere. Suffice it to note that the totemic concepts of the Dinka, as so well described in Godfrey Lienhardt’s Divinity and Experience (1961), provide one possible answer to the problem posed in the Australian case concerning the character of the human aspect of totemic animals. Given the “hybridity” or shared being of totemic species with their human congeners, as Philippe has emphasized, the Dinka answer is quite logical: the totem species is the inner nature of its human fellows, and the human species is the inner nature of its totem fellows; hence some men may change into lions, and vice versa (117, 134, 171).2

I turn to the animism of analogism, privileging in particular the Polynesian version as instanced in Hawai’i, since by comparison with Philippe’s exposition of other such ontologies, we have in Valerio Valeri’s Kingship and Sacrifice (1985) a sustained analysis of the unifying human logic in an otherwise bewildering plenitude of beings and things – or rather things as humanoid beings. For here the universe is encompassed in the persons of the great cosmocratic deities, each ruling a domain (kuleana) consisting of living humans, anthropomorphic images, and a multitude of cultural activities and natural phenomena. All of these entities are so many of the gods’ “myriad bodies” (kino lau), forms in which the deity is instantiated in myth, ritual, and ritualized practices – including technical activities. The myriad forms of the god-person endow these activities with the power of his being – or what’s a meta for? “By transforming himself into different myriad bodies,” Valeri writes, “by his power of metamorphosis...