![]()

1 Introduction

1 Introduction

There is a systematicity in how a verb’s meaning changes because its inner aspect and argument structure change in predictable ways. This book will take as a basic point of departure that there are three aspectual verb types, durative, telic, and stative aspect that determine the basic orientation of a verbal root. Unergative verbs are durative and their basic theta-roles are an Agent and incorporated Theme; unaccusatives are telic and their basic theta-roles are a Theme and optional Causer; subject experiencer verbs and (many) copulas are stative and have a Theme and optional Experiencer. Sorace’s (2000) continuum can be seen to express this threefold division.

The book shows shifts from intransitive to transitive verbs and from intransitive to copula verbs and draws conclusions about the mental representation of argument structure. Unergative verbs have durative aspect with an obligatory Agent and can be reanalyzed as transitive verbs, keeping their Agent and durative aspect but using their incorporated Theme (e.g. dance) as both a verb and Theme. Unaccusatives are telic with a Theme and are reanalyzed as causatives by adding a Causer but not as transitives because their aspect is incompatible. Unaccusatives also reanalyze as copulas because that change retains the Theme and the aspectual properties and only changes the categorial designation from verb to copula. My conclusion will be that the verb minimally has a Theme and a certain aspect and that the addition of the other arguments depends on this initial setting.

Throughout the history of English, there has been an increase both in (a) synthetic marking and (b) analytic marking of the argument structure. As for (a), the increase in labile verbs is responsible for (zero) morphology, marking alternations. As for (b), the loss of transitivizing prefixes and the increased use of light verbs, such as make, do, put, and get, and particles, such as off and away, contribute to increased analyticity. These light verbs and particles make visible the positions in which the arguments are merged. Apart from light verbs and particles, dummy it and cognate and reflexive objects are used to change, reduce, or increase the transitivity of a verb, all through analytic means.

These elements make the underlying aspectual structure visible. This structure can be coerced into another aspectual state through external means. Arguments that are definite and grammatical aspect that is perfective add to the transitivity of an event. Perfective aspect helps emphasize the telic nature and imperfective aspect the durative nature of the event. Marking definites and aspect has changed dramatically in the history of English. Where Old English has specialized case and some use of demonstratives to mark definiteness and verbal prefixes and inflections to mark aspect, Modern English uses articles for definiteness and particles and auxiliaries for aspect. Although the marking has changed, most verbs retain their basic inner aspectual structure throughout the history of English. An interesting exception is psych-verbs.

Psych-verbs, such as frighten and fear, involve Experiencers that function either as grammatical objects or subjects. The object Experiencers, which involve a (telic) change of state, are reanalyzed in the history of English as subject Experiencers but not the other way round. The verb fear shows such a change because it means ‘frighten’ in Old English. There is quite a debate on the aspectual properties of these verbs. It is generally agreed that subject Experiencers are stative but that the aspectual properties of object Experiencers are not uniform (Arad 1998), leading possibly to diachronic instability. If object Experiencers are telic (e.g. in the case of ‘frighten’) and subject Experiencers stative, the change to subject Experiencer involves a loss of telic aspect. This may be due to a variety of factors.

New Experiencer object verbs arise through a reinterpretation of the Theme as an Experiencer. This change happened to stun, worry, and grieve, which initially only have an Agent and Theme that are reanalyzed as Causer and Experiencer. These rearrangements are sometimes the result of changes elsewhere in the grammar but sometimes, I argue, reanalyses adhere to an Animacy Hierarchy in (1), a pre-linguistic precursor of the Thematic Hierarchy in (2). For instance, if the Causer is inanimate and the Experiencer animate, there might be a reanalysis to get both back in line with (1).

- (1) Animacy Hierarchy

- 1st and 2nd person > 3rd person pronoun > proper name/kin term >

- human noun, animate noun, inanimate noun.

- (adapted from Whaley 1997: 173)

- (2) Thematic Hierarchy

- Agent > Causer > Experiencer > Theme > Goal

- (adapted from Jackendoff 1972: 43 and Belletti and Rizzi 1988: 344)

The clines in (1) and (2) are also relevant to the grammatical and pragmatic roles expressed in a sentence. Thus, subject and topic would be more often expressed by animate entities and Agents than object and focus would be.

Various researchers (Chapman and Miller 1975; de Hoop and Krämer 2005/2006) have shown that children use a prominence hierarchy for subjects and objects. Children less accurately interpret and produce sentences where the subject is less animate than the object. They also interpret the subject as more referential than the object. The sentences this is tested on are typically transitive with the subject as the Agent and the object the Theme.

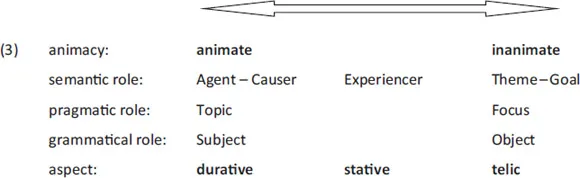

Putting (1) and (2) together with aspect and pragmatic and grammatical roles, we arrive at the cline in (3).

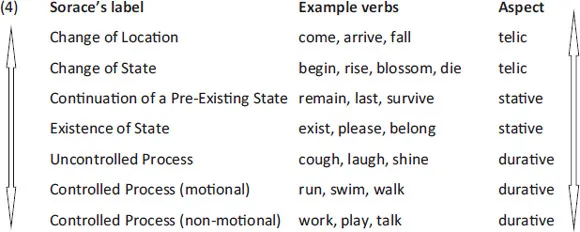

This continuum shows that Agent, Topic, and Subject are more typically animate and Theme, Focus, and Object are more typically inanimate. The durative aspect goes with an Agent whereas telic aspect needs a Theme. The Experiencer can accompany stative verbs. The three aspectual classes can be seen in Sorace’s (2000) Hierarchy and it may be possible to see them as a continuum, as in (4).

In this book, the focus will be on changes in the aspectual type and the kinds of aspect and theta-roles connected to a verb. I will discuss changes in the morphological marking of argument structure (the loss of affixes, an increase in particles, and the development of articles) as possible causes for these changes. In this introductory chapter, I discuss why argument structure matters to linguistics and beyond (section 2), what debates go on regarding argument structure (section 3), the role of language change for the faculty of language (section 4), and how I’ve gone about studying the verbs and what I have found (section 5), and finally I provide an outline (section 6).

2 Why Argument Structure Matters

Argument structure is crucial to the meaning of a sentence. All languages have verbs for eating, building, and saying and those verbs would have an Agent and a Theme connected with them. Arguments are also represented in the syntax in predictable ways. An Agent will be higher in the hierarchical structure than a Theme, unless they are clearly marked as not following the Thematic Hierarchy. Bickel et al. (2015) argue that “during processing, participants initially interpret the first base-form noun phrase they hear (e.g. she …) as an agent”. I will argue in chapter 6 that this cognitive hierarchy is sometimes responsible for the reanalysis of a verb’s argument structure.

Bickerton (1990: 185) writes that the “universality of thematic structure suggests a deep-rooted ancestry, perhaps one lying outside language altogether”. If argument structure is also relevant outside the linguistic system, humans without language could have had it and so could other species. A knowledge of thematic structure is crucial to understanding causation, intentionality, and volition, part of our larger cognitive system and not restricted to the language faculty. It then fits that argument structure is relevant to other parts of our cognitive makeup, moral grammar being one area. Pre-linguistic children connect agency with intention (Meltzoff 1995) and with animacy (Golinkoff et al. 1984), and relate cause and effect (Leslie and Keeble 1987). Hauser et al. (2007) have shown that moral judgments are not the same as justifications and that the former are likely part of a moral grammar. Mikhail (2011) argues that moral cognition has an innate, universal structure and Knobe (2003, 2010) has shown people have consistent judgments about intention, blame, and praise.

Argument structure and aspect play a major role in acquiring a theory of mind and a moral grammar. Agents may be assigned more responsibility than Causers; Goals are more salient than Sources (which Lakusta and Carey 2015 show for one-year-olds). Theta-roles themselves are a reflection of the deeper aspectual distinction in manner (durative and unbounded) and result (telic and bounded) that children are aware of from their first (English) words, using -ing with durative verbs and past tense -ed with telic ones. Thus, Snyder, Hyams and Crisma (1995), Costa and Friedmann (2012), and Ryan (2012) show that children distinguish intransitive verbs with Agents from those with Themes from when they start using these verbs. These aspectual distinctions, in turn, are connected to unbounded and bounded respectively. Children pay special attention to object shapes (Landau, Smith and Jones 1988) and (very young) children know the difference between objects (bounded) and substances (unbounded), as Soja, Carey and Spelke (1991) have argued, as do rhesus monkeys, which Hauser and Spaulding (2006) have shown.

Research into primate awareness blossomed in the late 1970s and 1980s, with Hulse, Fowler and Honig (1978), Premack and Woodruff (1978), and Griffin (1981). More recently, Gray, Waytz and Young (2012) argue that moral judgment depends on mind perception, ascribing agency and experience to other entities. De Waal (e.g. 2006) has demonstrated that chimps and bonobos show empathy and planning, and attribute minds to others.

As Pinker notes (2013: xv), the Minimalist Program (Chomsky 1995 to 2015) “adds … little new insight to … argument structure”. The reason for this lack of interest is probably because it lies outside of narrow syntax, as defined in Hauser, Chomsky and Fitch (2002). By attributing more to innate principles that are not specific to the language faculty (UG), “general properties of organic systems” (Chomsky 2004: 105) and principles of efficient computation (Chomsky 2005: 6) become more important. For instance, for the acquisition of lexical items, Markman (1994) argues that constraints on word learning, such as the one that words refer to objects as a whole and not their parts, are not specific to language. These factors are termed ‘third factor’ and for completeness, I provide all three in (5), where the first one is traditionally seen as Universal Grammar.

- (5) Three factors: “(1) genetic endowment, which sets limits on the attainable languages, thereby making language acquisition possible; (2) external data, converted to the experience that selects one or another language within a narrow range; (3) principles not specific to FL [the Faculty of Language]. Some of the third factor principles have the flavor of the constraints that enter into all facets of growth and evolution… . Among these are principles of efficient computation”. (Chomsky 2007: 3)

In connection to pre-linguistic knowledge, Pinker (1984) introduces the term bootstrapping, adopted by many, e.g. Gleitman (1990) and Naigles (1990): the idea that certain knowledge scaffolds other knowledge to lead to full acquisition. This book argues that the innate, pre-linguistic notions of durative, telic, and stative aspect and their theta-roles help a child acquire verb meaning.

3 Debates Regarding Argument Structure

Linguists can be divided into two broad camps: those who argue that the arguments are connected with the verb in the conceptual structure, e.g. Gruber (1965); Jackendoff (1972, 1983, 2002); Levin and Rappaport Hovav (1995); Grimshaw (1990); Tenny (1994); and those who think they are added by the syntax, e.g. Borer (2005); Lohndal (2014). Marantz (1984) and Kratzer (1996) argue that Themes (in the broad sense) are essential for the verb’s lexical meaning and conceptual structure but that Cause and Agent can be added as subevents and appear as structural positions in the vP. For them, idiomatic expressions provide evidence for this close relationship in that they claim that these typically occur between the verb and its Theme, as in kill time/the weekend/the bottle. This side downplays idioms with subjects, as in birds of a feather flock together (see Harley and Stone 2013).

My own position is that aspect and argument structure are part of the pre-linguistic conceptual structure. This can be phrased as a Lexical Relational Structure (Hale and Keyser 1993: 53) or a-structure (Grimshaw 1990: 1) or Conceptual Structure (Jackendoff 1983, 2002 and Pinker 1989/2013: 288–9) or Lexical Conceptual Structure (Tenny 1994: 187–8). These structures represent the verb with its basic aspect and arguments that are handed over to syntactic structure, represented in the vP-shell. Verbs are either durative and then have an Agent (and a Theme) or telic and then have a Theme (and a Causer). Ramchand (2008) and others see cause, process, and result reflected in the vP-shell as a representation of cognitive structure. I discuss this more in section 1.3 of chapter 2.

A major question arises concerning verb meaning, aspect, and argument structure that is highly relevant for linguistics. What is the set of concepts universal to our species and others? Within generative grammar, the first to stress a semantic representation are McCawley (1971) and Katz and Fodor (1963). They emphasize the universal character and a connection to the human cognitive system. They use semantic markers such as [human], [young], and [male] to decompose the meaning of a word “into its atomic concepts” (Katz and Fodor 1963: 186). Chomsky (1965: 142) writes that “semantic features … are presumably drawn from a universal ‘alphabet’ but little is known about this today and nothing has been said about it here”. The ability to categorize is not unique to humans, however. Certain animals are excellent at categorization; e.g. prairie dogs have sounds for specific colors, shapes, and sizes (Slobodchikoff 2010). As mentioned, Bickerton (1990) suggests that pre-linguistic primate conceptual structure may already use symbols for basic semantic relations, in particular theta-roles.

4 Language Change

I am assuming a model of language change where the language learner has an active role in language change. The learner has an innate knowledge of aspectual distinctions (duration and telicity) and categorizes verbs on the basis of the input. If a verb becomes ambiguous, as we’ll see happens through morphological erosion or aspectual coercion, the learner may analyze it in a different way from the speakers s/he is listening to. For instance, as we’ll see in chapter 5, the unaccusatives appear and remain are reanalyzed as copulas because what was formerly an adverb became ambiguous between adjective and adverb. This view of language change has been articulated in Klima (1965) and adapted by Andersen (1973), Lightfoot (1979), and van Gelderen (2011a), to name but a few.

Children acquire language using principles of Universal Grammar, e.g. use ‘internal merge’, and also pre-linguistic, cognitive ones, such as use (external) merge; use categories you already know; and analyze linguistic and other input in the most economical way. These are the third factors mentioned in section 2. The verbal reanalyses described in this book are exciting in that they provide a window on the cognitive system underlying the language faculty, represented in the syntax by the vP-shell. Because argument structure and syntax are different systems, the mechanisms of change in these systems also differ. In the syntax, there are principles of economy (see e.g. van Gelderen 2011a for reanalyses from phrases to heads and from heads with a lot of features to fewer features) that are not at work in the cognitive system. In fact, some verbs increase the complexity of their argument structure as they are reanalyze...