- 164 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Shape Memory Materials

About this book

This work addresses the basic principles, synthesis / fabrication and applications of smart materials, specifically shape memory materials

Based on origin, the mechanisms of transformations vary in different shape memory materials and are discussed in different chapters under titles of shape memory alloys, ceramics, gels and polymers

Complete coverage of composite formation with polymer matrix and reinforcement filler conductive materials with examples

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

Introduction

Stone Age, Bronze Age, Iron Age, and Silicon Age are the names given in the timeline of human civilization history based on the materials in use in each period. Each of these periods evolved technologically and culturally to the next era, primarily through advancements in the field of materials science. The significance of each era is portrayed based on the utility of a particular material. The evolution of the ages has witnessed the invention and discovery of newer materials, bringing a change to each era by itself.

The demand for lighter, stronger, and more reliable materials has resulted in the study of a new prospect called multifunctional materials. A specific subgroup of such materials with the capability to sense, process, and respond to external stimuli are referred to as smart materials. The past few decades have witnessed the development and progression of an extensive array of smart materials for numerous applications in the fields of medicine, mechanics, robotics, aerospace technologies, and so on. Smart materials are those engineered materials that are capable of altering their properties by sensing and responding to environmental conditions. Since the discovery of piezoelectricity (the property of a domain of materials that generate an electrical voltage in response to applied stress) by Pierre and Jacques Curie (1880), the era of smart materials was born and has evolved functionally and theoretically through further studies. Based on the definition of smart materials, a large domain has been identified and categorized as follows: piezoelectric materials, quantum tunneling composites, magnetostrictive materials, light-responsive materials, smart inorganic polymers, halochromic materials, chromogenic materials, photochromic materials, ferrofluids, photomechanical materials, dielectrics, thermoelectric materials, and shape memory materials (SMMs).

The late 1960s witnessed the pioneering concept of synthesizing smart materials for engineering/scientific applications, and these have been used in actuators, vibration damping, microphones, sensors, and transducers. These concepts were primarily based on three approaches, detailed as follows:

• Atomic/molecular-level synthesis of new materials (e.g., doping silicon/gallium to impart semiconducting properties), which emphasizes novel material development targeting specific applications

• Conventional structures with embedded sensors/actuators (e.g., self-healing materials), where smart properties are exploited for existing structural configuration enhancements

• Composite materials with properties superior to their individual components (e.g., shape memory polymer composites [SMPCs], as explained in a later chapter)

1.1 Smart Materials

The phrase smart materials refers to those materials, or combinations thereof, that change physically or chemically by sensing and responding to specific environmental stimuli, such as heat, magnetism, electricity, moisture, and so on, and return to their original configuration upon withdrawal of the stimuli.

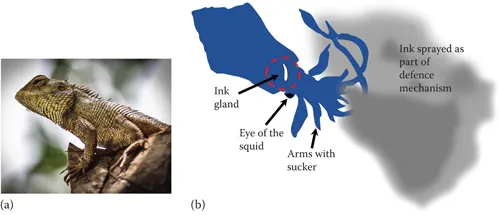

Nature has always been an inspiration for the development of many stimuli-responsive systems. Engineers have attempted to mimic and develop materials and methods that would artificially respond to such environmental conditions as nature does. The camouflaging of a chameleon or zebrafish, a squid changing its body color to match its surroundings, and the Mimosa pudica (touch-me-not) plant responding to the sensation of touch are a few among many known examples.

The outermost layer of the chameleon’s skin is transparent, below which are specialized cells called chromatophores that are filled with sacs of different kinds of coloring pigments. Based on body temperature and mood, specific chromatophores expand, releasing specific colors (Figure 1.1a).

FIGURE 1.1

Smart responses from nature. (a) Chameleon changes its color corresponding to the environment (courtesy of Whitelily—Pixabay [CC0 Creative Commons]). (b) Squid ejecting ink to escape from its predators.

Smart responses from nature. (a) Chameleon changes its color corresponding to the environment (courtesy of Whitelily—Pixabay [CC0 Creative Commons]). (b) Squid ejecting ink to escape from its predators.

The squid has color-changing cells with a central sac holding granules of pigment. The anatomy of the squid is such that this sac is encapsulated by muscles. Contraction of the muscles results in the spreading of the pigment/ink granules around the body, thereby blocking the line of sight of predators (Figure 1.1b).

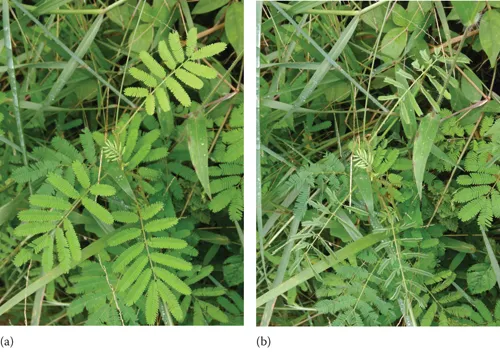

The unique touch–response property of M. pudica has been studied extensively to understand smart traits such as habituation and memory, which are properties of the Plantae (scientific name for plant) kingdom. Habituation refers to adaptation to the environment and ceasing to respond to nonrelevant biological events, while memory refers to responding to a specific stimulus.

On being disturbed externally by physical touch, various chemicals such as potassium ions are released in certain regions of the plant body. These chemicals are capable of initiating the flow or diffusion of water or electrolyte into or out of cells. This results in a loss of cell pressure. Thereby, the cell collapses, which causes the leaves to close. When this stimulus is transmitted to neighboring leaves, it initiates a process that gives the impression of “touch me not” (Figure 1.2a,b). This is nature’s defense mechanism against predators or insects that feed on leaves. Even though this occurs at the expense of energy gained through photosynthesis, the leaves respond smartly to the external stimuli, illustrating a natural smart material concept. The closed leaves gain back their original open configuration upon the withdrawal of the stimuli. This demonstrates the stimuli-responsive nature of the plant as well as its shape-memorizing ability. Nature provides many such depictions of stimuli-responsive systems that can be adopted to materials/structures/methods used in our daily life. For example, spacecraft antennas are exposed to extreme temperature changes, resulting in dimensional variations (due to expansion or contraction) and its attendant problems. It is inevitable that these materials should have very minimal variations in their dimensions for their best performance. The employment of smart materials for such applications is therefore pertinent. A smart antenna in such a situation shall sense the change in dimensions, judge the correction requirements, and autonomously bring the structure to its best performance. Conventional materials behave in an inert manner, whereas smart materials take over the situation intelligently to provide solutions that overcome the problem. Such smart materials are primarily driven by applications, and the general rules of physics and mechanics are defied, making them unconventional but demanding functional materials. For example, conventional materials when subjected to temperature will become soft and can be molded to the desired shape. Applying the same temperature again shall not bring back the original“predeformed” shape unless acted on by an external force, while many smart materials such as SMMs (as explained in Chapters 2 through 6) are found to behave differently under such situations, thus defying the general rules coined on understanding the behavior of materials so far. Sensing, actuating, and controlling capabilities are intrinsically built into the microstructure of such materials to make a judgment and react to the changes in ambient environment conditions. These stimuli can be changes in temperature, the presence of an electric/magnetic field, moisture, light, adsorbed gas molecules, and pH values, as reported by the scientific community.

FIGURE 1.2

Stimuli response from nature. (a) M. pudica plant leaf open. (b) Leaves close in response to touch; the receptors present in the plant’s body are activated by an alteration or modification of the plant’s shape.

Stimuli response from nature. (a) M. pudica plant leaf open. (b) Leaves close in response to touch; the receptors present in the plant’s body are activated by an alteration or modification of the plant’s shape.

The challenges to be addressed are in the selection of the best fabrication methods, the choice of reliable materials for specific functional combinations, and the preparation of materials to a particular density for use in the aerospace and biomedical fields. Material scientists across the world are simplifying the acceptance criteria for smart materials over usual resources, resolving the bottlenecks. They also help in exploiting the properties of smart materials and witnessing a gradual transformation from conventional materials to smart materials in all disciplines.

1.2 Stimuli-Responsive Materials

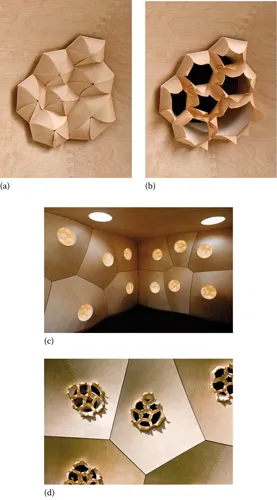

Let us imagine a window that responds to environmental conditions and adjusts itself in such a way that it provides comfortable living by controlling factors such as ventilation, humidity, and temperature to defined values. Such a structural object, the “HygroSkin” metereosensitive (abnormally sensitive to weather conditions) biomimetic (the imitation of models, systems, and elements of nature as a solution to complex problems) window pavilion, has been developed by Professor Achim Menges and his team in Orleans, France.

The concept is based on grain direction and the bending stiffness of thin wooden flaps that can absorb air moisture and expand. This opens up the possibility of regulating the perfect living conditions, requiring no human intervention. Figure 1.3a,b depicts the closed configuration and the open configuration for less humid and considerably more humid conditions, respectively, by expanding along the absorbed side to open the thin wooden flaps. Figure 1.3c,d shows the internal and external view of the HygroSkin, respectively, for varied humidity conditions. Thus, by sensing environmental changes, the material responds or actuates to achieve a functional requirement. This is an example of the stimuli-responsive concepts that have evolved as the building blocks of smart structures.

FIGURE 1.3

HygroSkin biomimetic smart structure from smart materials. (a, b) Element-level demonstration of the concept. (c, d) Structure-level demonstration. (From Correa, D., et al., 2013. HygroSkin: ...

HygroSkin biomimetic smart structure from smart materials. (a, b) Element-level demonstration of the concept. (c, d) Structure-level demonstration. (From Correa, D., et al., 2013. HygroSkin: ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half-Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Foreword

- Preface

- About the Authors

- 1 Introduction

- 2 Shape Memory Alloys

- 3 Shape Memory Ceramics

- 4 Shape Memory Gels

- 5 Shape Memory Polymers

- 6 Shape Memory Hybrids

- 7 Shape Memory Polymer Composites

- 8 High-Temperature Shape Memory Materials

- 9 Electroactive Shape Memory Polymer Composites

- 10 Discussions and Future Prospects

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Shape Memory Materials by Arun D I,Chakravarthy P,Arockia Kumar R,Santhosh B in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technology & Engineering & Materials Science. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.