- 394 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Bryology for the Twenty-first Century

About this book

A compilation of state of the art papers on key topics in bryology from invited speakers at the Centenary Symposium, University of Glasgow, 57 August 1996.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Bryology for the Twenty-first Century by Jeffrey W. Bates in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Biology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1. The life and work of Paul Westmacott Richards December 19, 1908–October 4, 1995

Queen Mary and Westfield College, London, U.K.

It is most fitting that this centenary volume of the British Bryological Society contains a tribute to Paul Richards, the man who more than any other was responsible for the rejuvenation of the Society after the Second World War and who translated it into its present form (Richards, 1983). The ethos of the Society perhaps embodies all that Paul lived and believed it should be; a collection of people from all walks of life drawn together as equals by a love of bryophytes. Thus the membership embraces amateur field bryologists, laboratory-based professionals, beginners, experts, the very young and the old(ish) all enjoying bryophytes together as friends.

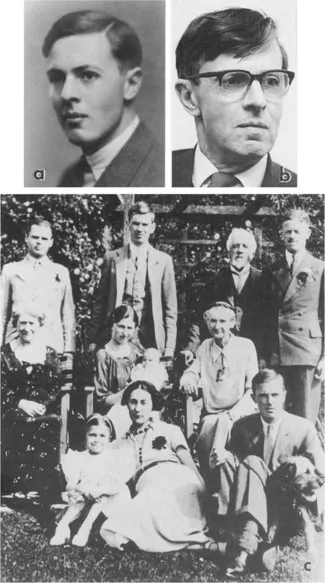

It is not the intention here to provide a detailed chronology of the life and works of Paul, these can be found elsewhere (e.g. Willis, 1996; Stanley, Argent & Whitehouse, 1998), but instead to share with you some of my own memories and to try to put into a personal context a few of the many things he did in a very long, varied, happy and fulfilled life. In a sense Paul was an allegory of the multidimensional nature and the timelessness of the BBS. On the one hand he was an international scientist with the remarkable talent of being able to comprehend both the very large, from tropical forest biomes, to the minutiae of bryophyte taxonomy. He was a talented linguist, a literary man deploring split infinitives, verbalized nouns and the corruption of botany to plant biology, a lover of music (particularly Bach, Brahms and Mozart) and a man of unobtrusive wisdom with tremendous diplomatic awareness and foresight. On the other hand there was about Paul himself a timeless quality (Fig. 2a, b). Throughout the 30 years I knew Paul, he always looked, behaved and talked exactly the same; quiet, gentle and wise, with a keen, dry sense of humour (Fig. 3a), but not really up to much physically. As one of Paul’s favourite anecdotes reveals, he always appeared frail. On being accepted for his first expedition to the tropics, British Guiana 1929, the leader, one Major R. W. G. Hingston, stated ‘I think we will take young Richards but I doubt whether we will bring him back’. Just before retirement from the Chair of Botany at Bangor he was still climbing trees in the tropics (Fig. 5b) and long after continued to scamper around the most rugged crags of Snowdonia in much the same way as he must have done as a boy, never giving it a second thought that people of his age weren’t supposed to do that sort of thing. As late as 1993, during the field meeting of the BBS at Ripon, the mid octagenarian Paul, supposedly with a worn-out hip joint, descended several 100 feet of muddy, slippery bank to observe Orthotrichium sprucei by the River Ure. Appropriately the previous day he had delivered a magical lecture on the life of Richard Spruce (Richards, 1994). Clearly Paul’s frailty belied a robust constitution and indomitable spirit — undoubtedly one of the reasons why he achieved so much in wild and hazardous places.

Paul Richards enjoyed botany for over 80 years and much has been written about his travels, scientific publications and work for conservation, particularly of tropical forests. Collectively these achievements are best recognized by honours such as his Cambridge ScD in 1954, the CBE in 1974 and the Gold Medal of the Linnean Society in 1979. What is perhaps not so widely recognized is that Paul was born a botanist — he would have been a botanist regardless. But most fortunately he was born into a situation which enabled the full expression of his genotype.

Paul, the youngest of four sons of H. Meredith Richards (Fig. 2c) was born at Walton-on-the-Hill, Surrey on 19 December 1908. At that time his father was M.D., MOH for Croydon, but in 1911 moved to a senior post in the health service at Cardiff. From his earliest years Paul was encouraged by his father and his brothers, particularly Owain to pursue an interest in Botany for which he clearly had considerable talent. By the age of 8 he had a good working knowledge of the larger British flowering plants and was already looking towards smaller things — dune annuals and mosses. Regrettably I never asked him why he did such things, the answer would probably have contained a mixture of, an intrinsic curiosity about beautiful things, the love of wild places and the challenge — intellectual and physical. During these formative years Paul was also encouraged by the field botanist Eleanor Vachell and by Arthur Wade, then an assistant in the Herbarium at the National Museum of Wales. He joined the Botanical Exchange Club (the forerunner of the Botanical Society of the British Isles) in 1919 — soon publishing his first note (Report of the Botanical Exchange Club, 1919, 5: 682); ‘Allium sibiricum L. Collected at Mullion; cultivated at Cardiff, it lost all its distinguishing characters and is indistinguishable from Schoenopraesum’ G.C. Druce then added ‘This note from our youngest member is worth testing’. Membership of the Moss Exchange Club followed in 1920.

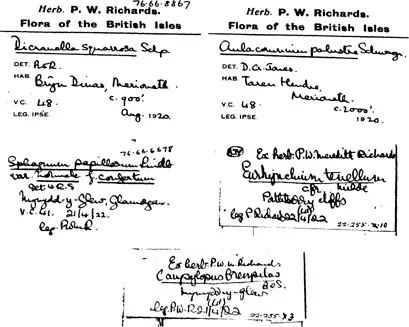

Some of his earliest herbarium specimens in the BBS herbarium (Fig. 1) clearly demonstrate that by his early teens Paul was already competent at bryophyte identification. One of the most significant events of these early bryological years was his first meeting with the distinguished bryologist D. A. Jones. In 1920, following what must have been a very adult letter, asking if he might visit Jones to discuss mosses, Paul took the train to Harlech, during a family holiday at Towyn, and duly arrived at Jones, doorstep, ‘Where is your father?’, ‘But I am Paul Richards’. ‘Oh Cambria stern and wild, meet nurse for botanic child’ (ad hoc adaptation from Scott, The Lay of the Last Minstrel by Dr Pegler who was also present at this meeting). Needless to say they both became great friends — very much in keeping with the whole of Paul’s life. He was a man who established enduring friendships with those from all walks of life. Occasionally however this non-hierarchical nature and disregard for rank, status and formal protocol landed him in trouble. After some three decades as Professor of Botany at Bangor, Paul decided that it was appropriate to write to his fellow Botany Professor at Leeds on first name terms. Professor Manton’s reply was unequivocal, ‘You must never write to me as Irene, the secretaries are bound to come to the wrong conclusion’.

The Richards’ family returned to London in 1920 whereupon Paul was an active participant in lectures and field excursions from the South London Botanical Institute thereby establishing life-long friendships with other bryophilic schoolboys including E. C. Wallace and D. G. Catcheside. He attended University College School from 1920–5 and University College London from 1925–7. Counter-balancing the paternal scientific influence his mother encouraged Paul’s facility with languages. A four month visit to Zurich in 1925 not only gave him fluency in German (he was already competent in French via tuition from a French governess) but also led to a meeting with Carl Schroeter and further field excursions.

Figure 1. Specimens in the British Bryological Society Herbarium, National Museum of Wales, Cardiff reveal the teenage Paul as a more than competent moss taxonomist.

In 1927 Paul won an entrance scholarship to Trinity College Cambridge where he was an exact contemporary of T. G. Tutin and E. F. Warburg. He also became friends with many others who went on to outstanding careers. Perhaps the seminal event in his undergraduate career was taking part in an expedition to British Guiana organized by the Oxford Exploration Society. This expedition, followed by others to Sarawak (1932) and to Southern Nigeria (1935), laid the foundations for The Tropical Rain Forest (1952) started before World War II but not published until 1952 following further visits to Nigeria and British Cameroon. Opening my own copy of this book, purchased as an undergraduate in the 1960s, I was surprised to discover almost everyone of its 407 papers heavily annotated. Now, with the hindsight of my own visits to tropical forests I realise the supreme strengths of this volume. Paul made sense out of the most complex ecosystem in the world producing at the same time an enthralling read. This book also provided the scientific foundation for the conservation of tropical forest. TRF and the subsequent popular book The Life of the Jungle (1970) are written by a man whose heart is in the subject and by one who has a gift for describing forests exactly as they are. You feel and smell the growing jungle in Paul’s works. Interestingly Paul’s later bibliographic writing displays the same uncanny sensitivity at distilling the true essence of the people about whom he wrote.

Figure 2. a, and b, Portraits of Paul as a research fellow, 1934 and on his retirement in 1976. c. The Richards family in 1935. Standing left to right; Brothers Gower, Owain, Father Harold Meredith and Brother Alan. Seated; Mrs Norris, Maud’s mother, Maud (wife of Owain) with baby Gillian and Mother Mary Cecilia. On grass Daughter Ann, now Mrs Venables, Nina (wife of Gower) Paul and Bill ( = dog).

After graduating with First Class Honours in both parts of the Natural Sciences Tripos, and the award of the Frank Smart Prize in Botany in 1931, Paul needed a means to live in Cambridge. Throughout his life he freely acknowledged that his greatest debt of gratitude was to Trinity College for the award of a research studentship followed by a fellowship thus enabling him to do what he really wanted namely to develop his tropical work, without the need to earn money and unencumbered by teaching and administration.

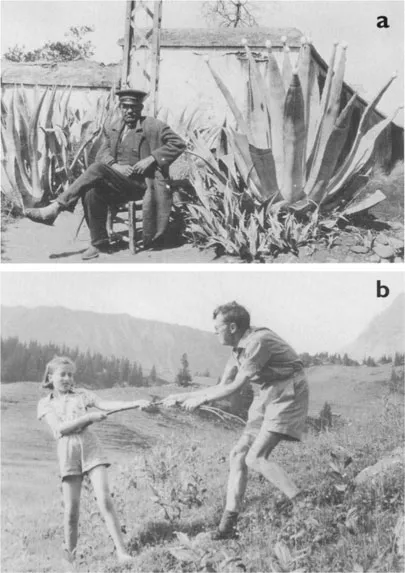

In 1930 Paul was introduced to Anne Hotham by Tom Harris whilst Anne was working on the Barnwell peat beds just before the 1930 Botanical Congress in Cambridge. Drawn together by the Biology Tea Club and a mutual love of music and plants the courtship survived the interruption of Paul’s 1932 Borneo expedition until, at a summer camp at Studland in 1934, Anne announced that she had been offered a job in South Africa which prompted Paul to propose before leaving for 6 months in Nigeria. The couple became engaged in November 1934 and married in December 1935 after Paul’s return from Southern Nigeria. This most happy marriage in some respects mirrored that of Paul’s parents. Anne and Paul had four children (Fig. 3b) whom they took on numerous family holidays to beautiful and wild places (Fig. 4a). Apart from marriage, breeding and tropical expeditions, Paul travelled widely in Europe. Though much of the research was written up, in papers ranging from his early bryological works on the mosses of Glamorgan (1923), and Middlesex (1928) to his early tropical papers on the rain forests of British Guiana (1934) and Sarawak (1936), other treasures have been lost to science (Fig. 3a).

Paul began life as a PhD student in plant physiology (of Prunus laurocerosus) in 1931 under the supervision of F. F. Blackman, physiology then being the area most in vogue. Sensibly, and quickly, he realised that his interests and talents lay not in experimental work but in observation and description — ‘the reading of vegetation’. After 2 weeks Prunus was forsaken in favour of comparative studies of rain forests under the watchful eye of Harry Godwin and with encouragement from Agnes Arber and E. J. Salisbury. Other catalysts towards this new direction were Schroeter’s Pflanzenzenleben der Alpen and a symposium on European beech forests at the Cambridge Botanical Congress in 1930.

The war years interrupted work on The Tropical Rain Forest but were not entirely bereft of botany or unproductive. Paul as a University demonstrator (from 1938) was the youngest member of the Botany School not to be called up on condition that his vacations be devoted to Government work. Initially his instruction was to search England for Frangula alnus used to make fuses and previously imported from France; a car and petrol allowance were provided. When Frangula was superseded by electronic fuses in 1942 he worked for the Naval Intelligence Division contributing to Geographical Handbooks on how to get ashore and survive in alien lands. It is fortunate that these war works were so down to earth and did not involve equipment. Though Paul was clear thinking with matters organizational, and practical when it came to plants and gardening, understanding machinery was not his forte. This minor failing is perhaps best illustrated by an incident involving the automobile. Paul drove throughout his life and on the open road never had an accident. He became proficient as a driver, according to his father, after only five of the six lessons recommended at a time before the days of compulsory driving tests. Reversing (lesson 6) into a garage however was not without its problems, whilst the workings of the machine remained a mystery and at times even the external features could be arcane in the extreme. During trips abroad Paul was in the habit of asking research students to look after his car and keep it in running order. One particularly conscientious student drove the car daily to and from the University. On the eve of the Richards’ return to his horror he discovered a broken rear light. This was repaired and an immaculate vehicle returned to its owner. Invited to tea a few days later Anne remarked, ‘I don’t know what is coming over Paul these days— just before we went away he told me he had broken a rear light on the car whilst reversing into the garage but now there’s nothing wrong with it’!

Figure 3. a. The ‘egg’ plant, (Pseudoagave mirabilis Nomen et planta fabricata), S. Spain with T. G. Tutin in 1931 — male left, female right. Paul travelled widely in Europe during the 1930s. Some of his more remarkable discoveries (un) fortunately w...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- PREFACE

- CONTRIBUTORS

- Welcome to the Centenary Symposium

- PART 1. A SPECIAL TRIBUTE

- PART 2. ORIGINS, EVOLUTION AND SYSTEMATICS

- PART 3. MORPHOGENESIS AND CELL BIOLOGY

- PART 4. PHYSIOLOGY, ECOLOGY, POLLUTION AND GLOBAL CHANGE

- APPENDIX

- INDEX