![]()

PART I

Issues in the Background and Foreground

![]()

1

Inclusive Mind-Sets and Best Practices for Adolescents

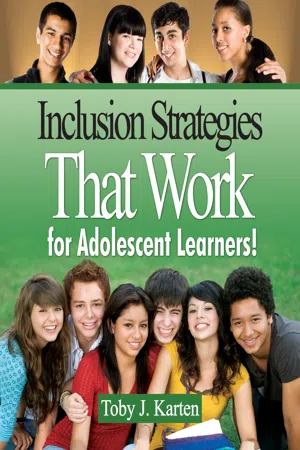

This chapter magnifies the value of collaborative teams of administration, staff, students, and families all being on the same page to assist adolescents to “capitalize” on and maximize their potential within inclusive classrooms. Detailed examination of available organizations and resources; a review of scheduling, preparation, reflection, and student responsibility; and a discussion of how to include students with varying ability levels using whole-class dynamics are offered.

Before inclusion strategies can be applied to adolescent classrooms, everyone involved needs to have an inclusive mind-set that says, “We can make inclusion work with the right strategies!” If that successful bottom line is the ultimate goal, then the objectives, materials, and procedures will be aimed toward achieving winning results. Peers, educators, administrators, families, and the students themselves are the ones who collaboratively need to believe that with guidance, practice, and perseverance, inclusive players win! Disabilities vary, but believing in abilities and planning lessons for student progress are essential. Yes, inclusive mind-sets precede the inclusive strategies and in turn yield inclusive winning results. Inclusion strategies for adolescents are complex, but they are also that simple.

Inclusion sequence:

Now, adolescents are unique individuals who sometimes try to exert control, never admit to losing control, test the people in control, and even create their own controls. Adolescents today are living in a world that at times through their eyes also appears out of control. How different their world is from ours! Just ask them!

Here is how some adolescents view life:

| Adolescent World | Other/Adult World |

Fact to share with adolescents: We live in the same world! Sharing this knowledge means teaching adolescents that the people who chronologically preceded them are intelligent, caring, trustworthy people. Establishing global adolescent connections is an ongoing inclusive mission that goes beyond individual classrooms into connective communities, cultures, and countries!

Philosophy to share: Here’s where the school system comes into play. We as educators must share the controls with the adolescents in our care. We figuratively and literally need to teach adolescents how to drive their own destinies. First, teach the rules of the road; next, practice with test drives; and then follow through with the actual driving test. Metaphorically speaking, classroom objectives lead to effective instructional strategies, which then yield meaningful assessments with passing grades on those classroom road tests or curriculum lessons for students of all abilities!

One Global World with As +As together (Adolescents + Adults)

ADOLESCENT DYNAMICS

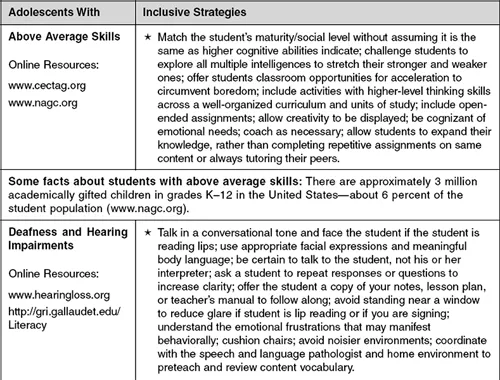

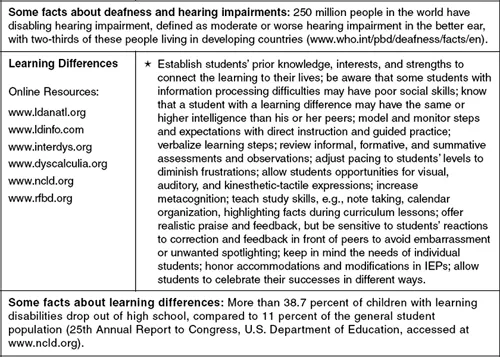

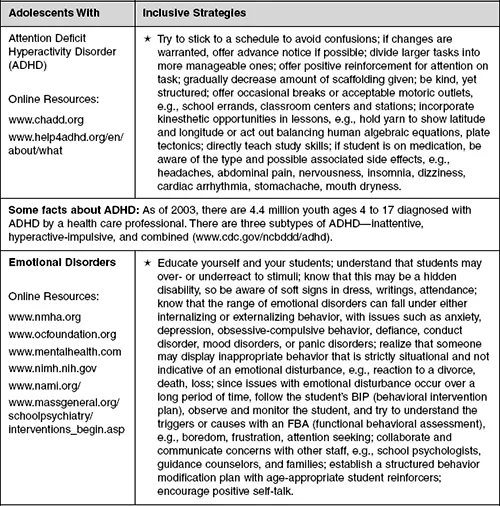

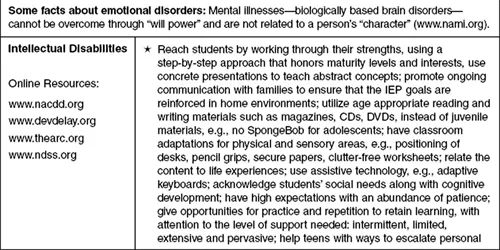

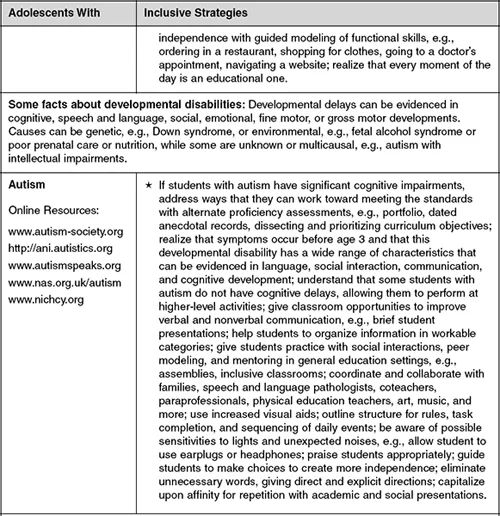

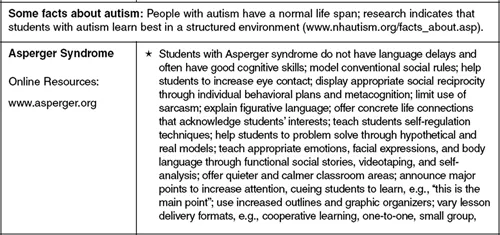

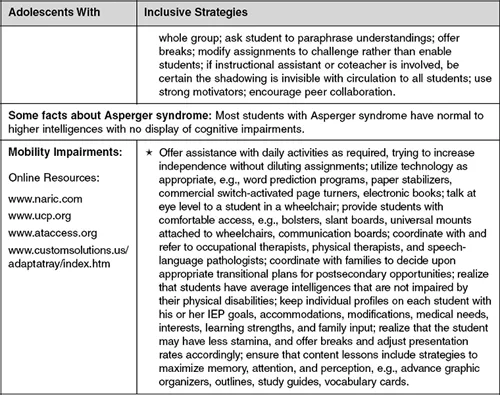

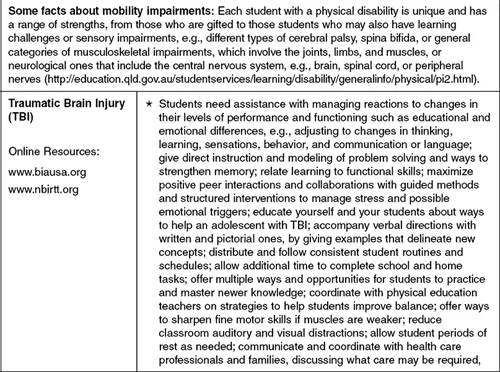

The plot thickens, due to adolescent issues in the foreground and background, for students with and without disabilities: adolescent tug-of-wars occur on a daily, hourly, and sometimes minute-by-minute basis. Students with more learning, emotional, behavioral, social, physical, perceptual, and communication needs often struggle to achieve cognitive acumen and peer acceptance in general education classrooms. Adolescents with disabilities in inclusive classrooms require inclusive practices that are able to focus on both background and foreground issues, with tailored strategies that address the diverse personalities and abilities of each adolescent. The following table gives some facts about student differences that may present themselves in inclusive classrooms, along with sensitive classroom strategies. More delineation of inclusive strategies with additional curriculum connections are offered as the book progresses.

Some additional foreground and background issues include adequate yearly progress (AYP), No Child Left Behind (NCLB), individual educational program (IEP), and response to intervention (RtI) which means that adequate yearly progress is expected for all students, legislatively not leaving any child behind. In the past, many students with disabilities were left in the background; now, yearly progress with more accountability is put into the foreground for all students.

IEPs—individualized education programs—are written with specific goals, outlining supports and appropriate accommodations to help students with disabilities to achieve many inclusive successes, if the general education classroom is determined to be the least restrictive environment. RtI—response to intervention—is also implemented in classrooms to help students receive assistance with direct academic training, smaller groups, or more outside help with classifications given as warranted. The National Association of State Directors of Special Education (NASDE, 2006) indicates that there are two main goals of RtI. The first is to deliver evidence-based interventions, and the second is to use students’ responses to those interventions as a basis for determining instructional needs and intensity. RtI involves lower student–teacher ratios, shared responsibility by general education (GE) and special education (SE) teachers and departments, data intervention groups with different delivery models, and more that will be outlined in subsequent chapters.

Classroom Environment: Factors such as class size, coteachers working together; a facilitative vs. authoritarian classroom atmosphere; heterogeneous vs. homogeneous groupings, seating arrangements; and cooperative groups, are just some of the environmental factors that positively or negatively impact adolescent achievements in inclusive environments. Proactive teachers monitor these variables and adjust them to best suit individual student needs without sacrificing the curriculum, emotional, social, and behavioral needs of all classroom students.

Student Dynamics: Issues such as gender; culture; socioeconomic status; physical, perceptual, emotional, behavioral, social, and cognitive abilities; motivation to succeed; self-efficacy; family support; and field-dependent versus field-independent learning styles are just a few student dynamics that enter into successful inclusion implementations.

Cognitive Factors: What about student and teacher prior knowledge, memory issues, varying instructional approaches, matching assessments with the curriculum, and targeting students’ strengths? Cognitively speaking, the brain is not to be ignored! Students respond to teachers who honor cognitive differences by offering scaffolding of learning within the students’ zone of proximal development to avoid adolescent learning frustrations, but also enhance comprehension of the curriculum with often difficult or unfamiliar topics. Graphic organizers, advance planners, teaching how to create study guides, modeling, offering multiple curriculum examples, and presenting learning with multiple intelligences in mind are just a few ways to respect cognitive differences in inclusive classrooms. More strategies with curriculum details and connections will follow.

Student Crises: Peer pressure, physical appearance, depression, eating disorders, suicide, identity issues, postsecondary decisions, sexual choices, wanting to belong, or wanting to be unnoticed are all potential crises that enter inclusive adolescent classrooms. Teachers who acknowledge these issues will accomplish more curriculum advances. It is often said that students remember how you treat them, long after they forget what you taught them. Kind, supportive teachers offer students nonjudgmental ears that accept differences, but do not magnify them.

Other School Activities: Adolescents with disabilities reap many benefits when they are included in extracurricular activities such as the yearbook committee, drama club, school newspaper, band, chorus, technology club, track and field, cheerleading, future teachers’ group, Spanish club, and more!

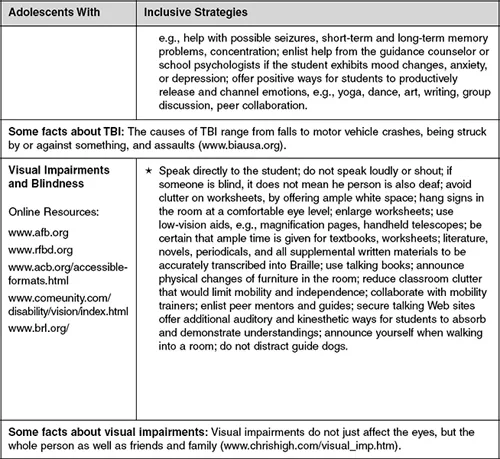

Review the columns in the next inclusive table to decide what actions (see the list below the table) you believe constitute excellent, good, fair, or noninclusive classrooms. Place the letters where you think they belong in reference to instruction and assessments, and then collaborate with colleagues and share thoughts with families and students.

| A. | High expectations for all students. |

| B. | Belief that students with l... |