![]()

1

Why Paraeducators?

What Experience, History, Law, and Research Say!

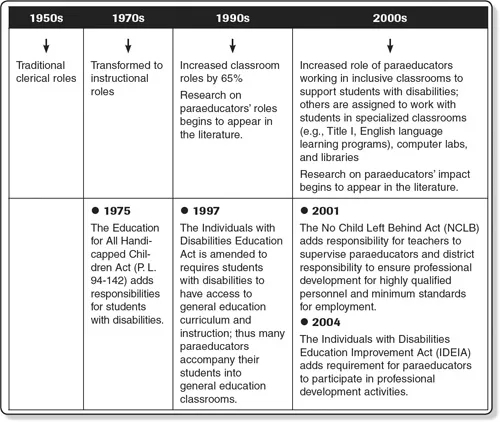

Figure 1.1

Paraeducators in Schools: A Time Line of Key Historical Events

The time line in Figure 1.1 shows that there are many key historical events that have influenced the way paraeducators work in today’s classrooms. As we begin, you may already be wondering:

- What are paraeducators?

- When did paraeducators first become a part of the American classroom?

- What does the research say about paraeducators?

- What are the current legislative mandates regarding paraeducators?

- What are the potential legal challenges?

In this chapter, you will learn the answers to these questions as they relate to paraeducators who work in inclusive classrooms.

WHAT PARAEDUCATORS ARE

First, what do we mean by the terms paraeducator, inclusive education, and co-teaching? In addition to being defined below, these and other terms that may be unfamiliar are found in the Glossary.

A paraeducator is a school employee who “provides instructional, safety, and/or therapeutic services to students” (French, 2008a, p. 1). Para-educators work under the supervision of a professional in a position that might have one of the following titles: teaching assistant, paraprofessional, aide, instructional aide, health care aide, educational technician, literacy or math tutor, job coach, instructional assistant, or educational assistant. The two most frequently used terms for describing a person in this role are paraprofessional and paraeducator. For example, the term paraprofessional is used in the U.S. federal law that governs the education of students with disabilities (IDEIA, 2004, Part D, Section 651). The term paraeducator has been used by some leading authors in the field, such as Pickett and Gerlach (2003), who speak from the perspective of paraeducators themselves. To honor the perspective of and to reflect the increased instructional role of paraprofessionals, in this book we use the term paraeducator.

Inclusive education, in our (the authors’) view, is a process where schools welcome, value, support, and empower all students in shared environments and experiences for the purpose of attaining the goals of education. Co-teaching is two or more people sharing responsibility for teaching some or all of the students assigned to a classroom (Villa, Thousand, & Nevin, 2008a). Co-teaching involves distributing responsibility among people for planning, instructing, and evaluating the performance of students in a classroom. Co-teaching is one example of an inclusive educational practice that allows general education teachers and others to provide students with and without disabilities access to the general education curriculum.

THE INTRODUCTION OF PARAEDUCATORS TO THE AMERICAN CLASSROOM

The history of paraeducators began in the 1950s, when they were introduced into schools to provide teachers more time for planning for instruction. For the most part, early paraeducators performed clerical services. They duplicated materials and they managed students in non-instructional settings such as the lunchroom or playground.

In the 1970s, federal legislation was passed that guaranteed students with disabilities access to a free appropriate public education. With the steady movement toward general education being the preferred primary placement for students with disabilities, the paraeducator’s role has evolved and is now primarily instructional in nature, especially when supporting students in the general education setting (Giangreco, Smith, & Pinckney, 2006; Pickett, 2002).

The increased reliance on paraeducators to assist in differentiating instruction in the classroom is evidenced by the numbers. For example, a comprehensive study of K–12 staffing patterns in all 50 states (National Center for Education Statistics, 2000) revealed that in the seven-year period from 1993 to 2000, the number of paraeducators in classrooms increased from approximately 319,000 to over 525,000, a 65% increase. Over half a million paraeducators were employed in inclusive and other educational settings supporting students with disabilities—the rest were assigned to support students in compensatory programs (e.g., Title I aides or multilingual aides). Some paraeducators worked in learning environments such as libraries, media centers, and computer laboratories. These data reveal the predominantly instructional nature of today’s paraeducators.

MEET PARAEDUCATORS: MS. O. AND MS. BEGAY

The many and varied roles of paraeducators also have been reported in the literature. Paraeducators usually discover they wear multiple hats as they juggle their roles and responsibilities. For example, paraeducators can be note-takers for students with hearing impairments as they attend classes (Yarger, 1996) or translators as well as tutors for children who speak languages other than English (Wenger et al., 2004). Teaching pro-social behaviors to young children (Perez & Murdock, 1999) and serving as aides to coach appropriate behavior for students with autism have been shown to be effective (Young, 1997). Paraeducators have also served as speech-language assistants (Radaszewski-Byrne, 1997), job coaches (Rogan & Held, 1999), or tutors for helping students learn to read, compute, or write (Ashbaker & Morgan, 2000). Other, more subtle, roles have included para-educators as cultural ambassadors who help educational personnel bridge the gap between monolingual professionals and bilingual communities (Koroloff, 1996; Rueda & Monzo, 2002) and those who help all the children in addition to those specifically assigned to them (Giangreco et al., 2006; Marks, Schrader, & Levine, 1999). Moreover, paraeducators are active in college classrooms to provide accommodations (Burgstahler, Duclos, & Turcotte, 1999).

Pamela O. serves as an example of a paraeducator who juggled multiple roles as part of her job in an inclusive multicultural magnet school for the arts in Miami, Florida. She instructed tutorials, provided playground supervision, and prepared materials. She worked for two years with a team of co-teachers who practiced “looping,” where they followed their third-graders when they were promoted to fourth grade (see Nevin, Cramer, Salazar, & Voigt, 2007). Ms. O. knew the fourth-grade curriculum because previously she had been a paraeducator for the fourth grade. She had some unique gifts that helped her relate to her students, such as her creativity in helping them construct posters to visually represent what they were learning. In fact, her general education teacher complimented her communication skills: “She’s not bilingual but she understands Spanish (her husband speaks Spanish) and she can speak basics to the kids. For example, the Cuban kids will go up to her and ask for help with no problem” (R. Puga, personal communication, May 24, 2006). Ms. O. was especially grateful for the added skills she learned when the guidance counselor included her in once-a-week social skills discussions and activities for the fourth-graders to learn to tolerate and respect each others’ differences. In her role as playground aide, she often asked the students to use those skills when they were involved in arguments at recess.

Another example of a paraeducator who juggled multiple roles at a junior high school is reported in a study conducted by Nevin, Malian, et al. (2007). Ms. Begay spoke English and Dakota Sioux and had worked for several years in other roles prior to becoming a paraeducator. She explained her work in a junior high school this way: “I work [in a classroom] with sixth-graders [where I tutor] in math and science, seventh-graders in science and social studies, where there are 10 students with disabilities. The students are learning to speak English as a second language, as they are all Native Americans. [Many of my students have] behavior issues due to lack of academic self-esteem.” Ms. Begay reported that she helped her students work in cooperative learning groups and as peer tutors. She firmly believed that the student who has trouble learning represents an instructional challenge rather than a “problem student.” She reported that she received support for how to differentiate her instruction and that her classroom routines helped meet the needs of her learners. She said that to prepare for her lessons, she reviewed lesson plans with her co-teacher. She emphasized to the authors of the study that the most important part of her job in the inclusive classroom was “to assist my students with strategies that are easier to understand. I make my special education students feel good about learning.”

WHAT THE RESEARCH SAYS ABOUT PARAEDUCATORS

In Chapter 3, you will discover more about the roles and responsibilities of paraeducators. Regardless of role, the literature is clear about the value of paraeducators in the classroom. For example, students with disabilities are included more in classroom activities when paraeducators are present. The presence of paraeducators makes it possible for all students’ instruction to be differentiated. General educators appreciate the presence of paraeducators, who are considered essential for supporting students eligible for special education in their classrooms (Downing, Ryndak, & Clark, 2000; Giangreco, Broer, & Edelman, 2002; Marks et al., 1999; Mueller & Murphy, 2001; Piletic, Davis, & Aschemeier, 2005; Riggs & Mueller, 2001; Villa et al., 2008a).

The California Department of Education has recognized 22 California sites for their collaborative approaches to including all students in inclusive environments. In such collaborative cultures, paraeducators often are given the same inservice training, are sent to conferences and workshops, and are asked to share their experiences with professional colleagues. Paraeducators also experience the benefits of being appreciated. For example, at Rincon Middle School in Escondido, California, the special education department chair said that people wanted to “transfer to Rincon because of the way instructional assistants are treated here. They are a part of the team: valued, respected, given the ability to make decisions” (Grady, 2007, p. 7).

Paraeducators from underrepresented populations (particularly those from marginalized populations, such as those who are culturally and linguistically diverse) can offer new perspectives and support for both children and teachers. As Ashbaker and Morgan (2000) suggest, paraeducators who are themselves bilingual can serve as role models as well as ambassadors who help teachers better understand the impact of culture and language on learning outcomes.

Parents and family members also appreciate what paraeducators do. They are clear about their preferences for how paraeducators might work with their children (French & Chopra, 1999; Palmer, Borthwick-Duffy, Widaman, & Best, 1998). For example, French and Chopra (1999) report the results of an exploratory focus group process involving mothers of 23 children who received special education services in general education classrooms, mainly through support from paraeducators. The paraeducators were believed to be compassionate and dedicated people who were important to the parents. Especially valued were their roles as team members, instructors, caregivers, and health needs providers.

Although parents are clear that paraeducators can be beneficial in their children’s education (French & Chopra, 1999), they are cautious and remain apprehensive about the quality of education their child actually receives in inclusive classrooms (Palmer et al., 1998). The most frequently identified problem is that the paraeducators often have limited training and support, which results in high levels of staff turnover. Parents want paraeducators and classroom teachers who work with their children to receive appropriate training and supervision. In addition, parents appreciate paraeducators who are creative about facilitating peer relationships. Paraeducators can do a lot to make sure that students assigned to them are not isolated and further stigmatized. Parents insist that the following issues should be handled before their child works with any paraeducator (Paula Goldberg1, Executive Director of the PACER Center):

- Be sure paraeducators know the child’s disability, techniques for positive behavior support, how to communicate with the child, and approaches to encourage independence and peer relationships.

- Paraeducators need clearly defined roles and responsibilities, which should ideally be written into the child’s academic, behavior, or language development plan.

- Parents want paraeducators to be included in their child’s team meetings and want them to update them on their child’s progress.

What do children say about working with paraeducators? Children’s voices are strikingly absent from the literature. Recently, some researchers have studied how children and youths talk about their paraeducators (e.g., Giangreco, Yuan, McKenzie, Cameron, & Flalka, 2005; Skär & Tam, 2001; Werts, Zigmond, & Leeper, 2001). Thirteen children and adolescents (aged from 8 to 19 years) with restricted mobility who lived in northern Sweden were interviewed (Skär & Tam, 2001). The results of the interviews yielded five distinctions with respect to their perceptions of their assistants. Some perceived their assistant as a substitute for their parent (mother or father). Others perceived their assistant as a professional or as a friend. All student...