INTRODUCTION

For your birthday you get some extra cash and decide to buy a new Bible. You go online thinking you can find what you want pretty quickly. Immediately you notice more choices than you had imagined. You see the NIV Study Bible, ESV Systematic Theology Study Bible, CSB Study Bible, Life Application Study Bible, Christian Basics Bible NLT, CSB Apologetics Study Bible, NIV Cultural Backgrounds Study Bible, NKJV Apply the Word Study Bible, and about fifty other options. You didn’t know buying a new Bible could be so complicated. What should you do?

The first thing to know about selecting a Bible is that there is a big difference between the Bible version or translation and the format used by publishers to market the Bible. Packaging features such as study notes, introductory articles, and devotional insights are often helpful, but they are not part of the translation of the original text. When choosing a Bible, you will want to look past the marketing format to make sure you know which translation the Bible uses. In this chapter we will be talking about Bible translations rather than marketing features.

Translation itself is unavoidable. God has revealed himself and has asked his people to make that communication known to others. Unless everyone wants to learn Hebrew and Greek (the Bible’s original languages), we will need a translation. Translation is nothing more than transferring the message of one language into another language. We should not think of translation as a bad thing, since through translations we are able to hear what God has said. In other words, translations are necessary for people who speak a language other than Greek or Hebrew to understand what God is saying through his Word.

ENGLISH TRANSLATIONS SINCE 16111

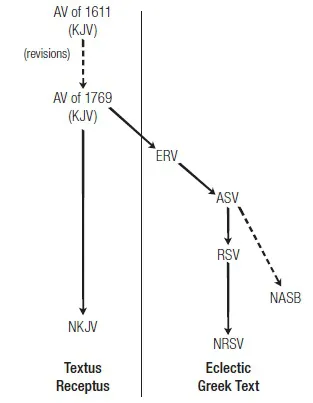

A number of more contemporary English translations have some connection (direct or indirect) to updating the King James Version. The English Revised Version (1881–85) was the first such revision and the first English translation to make use of modern principles of textual criticism. As a result, the Greek text underlying the ERV was different from that of the KJV. In 1901 American scholars produced their own revision of the ERV: the American Standard Version. Toward the middle of the twentieth century (1946–52), the Revised Standard Version appeared. The goal of the RSV translators was to capture the best of modern scholarship regarding the meaning of Scriptures and to express that meaning in English designed for public and private worship—the same qualities that had given the KJV such high standing in English literature. The English Standard Version (2001) is a word-for-word translation that uses the RSV as its starting point. Its goal is to be as literal as possible while maintaining beauty, dignity of expression, and literary excellence.

The New American Standard Bible (1971, rev. ed. 1995) claimed to be a revision of the ASV but probably should be viewed as a new translation. The NASB seeks to adhere closely to the form of the original languages. The New King James Version (1979–82) attempts to update the language of the KJV while retaining the same underlying Greek text that the translators of the KJV used (commonly called the Textus Receptus or TR).2 This preference for the TR distinguishes the NKJV from the other revisions, which make use of a better Greek text (commonly called an eclectic Greek text), based on older and more reliable readings of the Greek. The New Revised Standard Version, a thorough revision of the RSV, was completed in 1989 with the goal of being as literal as possible and as free as necessary. The accompanying chart illustrates the relationship between translations that are related in some way to revising the KJV.

In addition to the KJV revisions noted above, committees of scholars have produced many other new translations. Catholic scholars have completed two major translations: the New American Bible (1941–70) and the Jerusalem Bible (1966). What makes these significant is that not until 1943 did the Roman Catholic Church permit scholars to translate from the original Greek and Hebrew. Until that time, their translation had to be based on the Latin Vulgate. The New Jerusalem Bible, a revision of the Jerusalem Bible, appeared in 1985. Both the New English Bible (1961–70) and its revision, the Revised English Bible (1989), are translations into contemporary British idiom. The American Bible Society completed the Good News Translation in 1976 (also called Good News Bible or Today’s English Version). The translators of this version sought to express the meaning of the original text in conversational English (even for those with English as a second language). In the New International Version (1973–78), a large committee of evangelical scholars sought to produce a translation in international English offering a middle ground between a word-for-word approach and a thought-for-thought approach.

The New Century Version (1987) and the Contemporary English Version (1991–95) are translations that utilize a simplified thought-for-thought approach to translation. A similar translation from the translators of the NIV is the New International Reader’s Version (1995–96). The New Living Translation (1996) is a fresh, thought-for-thought translation based on the popular paraphrase The Living Bible (1967–71). A recent attempt by an individual (rather than a committee) to render the message of Scripture in the language of today’s generation is The Message by Eugene Peterson (1993–2002). The Message claims to be a translation but reads more like a paraphrase aimed at grabbing the reader’s attention. God’s Word Translation (1995) uses the “closest natural equivalence” approach to translation in an attempt to translate the meaning of the original texts into clear, everyday language. The New English Translation, commonly referred to as the NET Bible (1998), offers an electronic version of a modern translation for distribution over the internet. Anyone anywhere in the world with an internet connection (including translators and missionaries) can have access to this new version, which is under continual revision. The Lexham English Bible (2010–11) is an online Bible released by Logos Bible Software that is closely connected to the original languages. The Common English Bible (2011) is a fresh translation in the liberal Protestant tradition.

Today’s New International Version (2001) is an attempt to revise the NIV, using the best of contemporary biblical scholarship and changes in the English language. Most recently the Committee on Bible Translation has revised the most popular of all modern English translations of the Bible, the New International Version. The NIV 2011 incorporates many of the improvements of the NIV (1984) made by the TNIV but with more precision in the area of gender-inclusive language.

The Holman Christian Standard Bible (1999–2004) is a new Bible translation that promotes a word-for-word approach unless clarity and readability demand a more idiomatic translation, in which case the literal form is often put in a footnote. The Christian Standard Bible (2017) is a major revision of the Holman Christian Standard Bible that draws from both formal and functional translation philosophies.

Our survey of English Bible translations since 1611 has been a brief one. We have only hit the high points in a long and rich history. We move now to explore the different approaches to Bible translation.

APPROACHES TO TRANSLATING GOD’S WORD

The process of translating is more complicated than it appears. Some people think that all you have to do when making a translation is to define each word and string together all the individual word meanings. This assumes that the source language (in this case, Greek or Hebrew) and the receptor language (such as English) are exactly alike. If only the process could be so easy! In fact, no two languages are exactly alike. For example, look at a verse chosen at random—from the story of Jesus healing a demon-possessed boy (Matt. 17:18). The word-for-word English rendition is written below a transliteration of the Greek:

Kai epetimēsen autō ho Iēsous kai exēlthen ap’ autou to daimonion

And rebuked it the Jesus and came out from him the demon

kai etherapeuthē ho pais apo tēs hōras ekeinēs

and was healed the boy from the hour that

Should we conclude that the English line presented above is the most accurate translation of Matthew 17:18 because it attempts a literal rendering of the verse? Is a translation better if it tries to match each word in the source language with a corresponding word in a receptor language? Could you even read an entire Bible “translated” in this way?

The fact that no two languages are exactly alike makes translation a complicated endeavor. D. A. Carson identifies a number of things that separate one language from another:3

■ No two words are exactly alike. As we learned earlier in this chapter, words mean different things in different languages. Even words that are similar in meaning differ in some way. For example, the Greek verb phileō, often translated “to love,” must be translated “to kiss” when Judas kisses Jesus in an act of betrayal (Matt. 26:48 KJV and NIV).

■ The vocabulary of any two languages will vary in size. This means that it is impossible to assign a word in a source language directly to a word in a receptor language. This kind of one-to-one correspondence would be nice, but it is simply not possible.

■ Languages put words together differently to form phrases, clauses, and sentences (syntax). This means that there are preset structural differences between any two languages. For example, English has an indefinite article (a, an), while Greek does not. In English, adjectives come before the noun they modify, and they use the same definite article (e.g., “the big city”). In Hebrew, however, adjectives come after the noun they modify, and they have their own definite article (e.g., “the city, the big”).

■ Languages have different stylistic preferences. Sophisticated Greek emphasizes passive voice verbs, while refined English stresses the active voice. Hebrew poetry sometimes uses an acrostic pattern, which is impossible to transfer into English.

Since languages differ in many ways, making a translation is not a simple cut-and-dried, mechanical process. When it comes to translation, it is wrong to assume that literal automatically equals accurate. A more literal translation is not necessarily a more accurate translation; it could actually be a less accurate translation. Is the translation “and was healed the boy from the hour that” better than “and the boy was healed instantly” (ESV) or “and from that moment the boy was healed” (CSB)? Translation is more than just finding matching words and adding them up.

Translation entails “reproducing the meaning of a text that is in one language (the source language), as fully as possible, in another language (the receptor language).”4 The form of the original language is important, and translators should stay with it when possible, but form should not have priority over meaning. What is most important is that the contemporary reader understands the meaning of the original text. When a translator can reproduce meaning while preserving form, all the better. Translating is complicated work, and translators often must make difficult choices between two equally good but different ways of saying something. This explains why there are different approaches to translation. Individuals and committees have differences of opinion about the best way to make the tough choices involved in translation, including the relationship between form and meaning.

There are two main approaches to translation: the formal approach (sometimes labeled “literal” or “word-for-word”) and the functional approach (often called “idiomatic” or “thought-for-thought”). In reality, no translation is entirely formal or entirely fu...