![]()

Part 1: Language and Languages in Education

The first part of the book provides an overview of key aspects of both language education and the role of languages in education. Many of these aspects are referred back to in later chapters. The term ‘language education’ is usually associated with the teaching and learning of foreign or additional languages, and two of the chapters in this part focus on this kind of language education, one of them on the dominant role English now plays. However, in today’s world it is harder than it was even 30 years ago to draw a line between this kind of language education and the teaching and learning of the ‘language of schooling’, generally the language of the community or country in which the school or institution is situated. This is because it is no longer the case – and in many countries it was never the case – that cohorts of students in an educational institution are a monolingual and monocultural group. Even among the majority who share the national or regional language, there is considerable diversity in levels of literacy and ability to use oral language effectively, as well as in the varieties of the language they feel comfortable with. In addition to these considerations, we also discuss the way language is used by teachers in their work and the impact this has on learning.

![]()

1 The Crucial Role of Language in Education

We begin this first chapter with a wide-ranging overview of the vital role that language plays in education wherever the learning and teaching takes place, whatever the age of the learners and irrespective of the aims of the educators. Our purpose here is to set out aspects of language and languages in education that we consider to be of prime importance when addressing the challenges and opportunities referred to in our title.

First, we briefly consider the ground-breaking insights of Lev Vygotsky and his followers, and of others who fashioned the shape and principles of contemporary education in Europe and North America. We then look in more detail at how language works to facilitate the development of concepts and the raising of awareness in the interactions between those teaching and those learning. This leads naturally to a reflection on how language used in schools and other educational organisations links up with and prepares the way for coping with the complex multiple functions and uses of language in the real world, for example, to gain and exercise power, to sell goods and services, and in our role as citizens.

Language, Thought and Learning

‘Learning, in the proper sense, is not learning things, but the meanings of things, and this process involves the use of signs, or language in its generic sense’. This sentence from a chapter entitled ‘Language and the training of thought’ in John Dewey’s classic How We Think (Dewey, 1910: 175) is a good example of early 20th century views of education, child psychology and language. The great names in this tradition span the universities of the northern hemisphere from Vermont, where Dewey worked, to Neuchâtel, the home of Jean Piaget, and Moscow, the alma mater of Lev Vygotsky. The ways in which they presented their ideas, and in the case of Piaget and Vygotsky, their research findings, on the question of signs, language, thought and learning, are of their time, but the insights themselves remain important today and are often overlooked by teacher educators and teachers themselves. Broadly, they proposed that thinking and concept development are only possible with the help of language.

Vygotsky’s work and ideas have had a controversial history since his untimely death from tuberculosis in 1934. This is partly due to the incompleteness, censoring and amendments of the original Russian versions and the lack of reliable translations, but also to the promotion of simplified versions of his ideas in the West in the 1970s and since. Work is still ongoing on the first ever full version of Vygotsky’s complete works. The ideas reproduced here cannot, therefore, be regarded as a full or reliable representation, but they are very relevant to the purpose of this chapter. As Vygotsky put it, ‘[Word meaning] is a phenomenon of verbal thought, or meaningful speech – a union of word and thought’ (Vygotsky, 1986: 212). After close critical analysis of the work of Piaget and many others working in the field up to the 1930s, as well as practical research with children, it was clear to Vygotsky that concept development was dependent on language, and that instruction involving language and other semiotic systems had a crucial role to play in helping children to develop new conceptual frameworks and to enrich their existing understanding. For him it became evident that the learning of new concepts, notably ‘scientific’ concepts, is mediated by concepts that have already been acquired and by the language and other systems of signs (gestures, diagrams, etc.) in which they are represented.

In most learning from a very early age social interaction involving spoken language is key: even parents showing the world to their babies or encouraging them to eat, sit, walk or play use language of one kind or another as a constant soundtrack. Beyond babyhood, when children’s language is often an ‘egocentric’ accompaniment to their activities, and into adulthood, it is unusual for there to be thoughts and feelings without some kind of inner language, and it is apparent that this inner ‘speech’, as well as the mediation provided by others, plays its part in our ongoing, never-ending learning.

Language and Learning Objectives

Vygotsky was one of the first to describe the mediating function of language: its use as a tool to bridge the gap between what is familiar, for example known concepts, and what is not yet known or ‘other’. This process of ‘knowing’ was the focus of the Taxonomy of Educational Objectives developed by Benjamin Bloom and colleagues in the United States in the 1950s. The resulting model proposed six successive cognitive stages: knowledge > comprehension > application > analysis > synthesis > evaluation (Bloom, 1956). While the underlying assumptions behind the taxonomy have been disputed, the taxonomy has had considerable impact on educational thinking and research, especially in the USA, and has been followed up by revised versions, such as that developed by Lorin Anderson, David Krathwohl and colleagues (2001), and a more radical ‘new taxonomy’ created by Robert Marzano (Marzano & Kendall, 2007). Whichever of these one considers, and whatever view one has of their validity and usefulness, it is clear how prominently language features at all levels of the taxonomy. This interdependence of language, thought and learning, linking back to Vygotsky, is nicely illustrated by a correlation of action verbs with the categories of the taxonomy as revised by Anderson and Krathwohl (2001). As examples, ‘understanding’ is quite low in the hierarchy of the Revised Taxonomy and is associated with such verbs as ‘classify’, ‘explain’, ‘interpret’, ‘rephrase’ and so on. On the other hand, ‘evaluating’ is near the top, one step down from ‘creating’. Some verbs that are typically associated with evaluation, according to Anderson and Krathwohl, are ‘compare’, ‘deduct’, ‘explain’ and ‘prove’. The interrelationship between learning and using language in various ways is clear from such examples: even when learning autonomously, using words to explore what one is discovering is essential to the process.

As its original title suggests, Bloom’s Taxonomy was designed as an aid to the formulation of educational objectives for teaching any subject. It specified categories of knowledge as well as a hierarchy of cognitive processes. In Anderson, Krathwohl et al.’s revised taxonomy, the knowledge and cognition dimensions are divided into two complementary dimensions in which language remains a key factor. Broadly, as Krathwohl (2002: 213) explains ‘statements of objectives typically consist of a noun or noun phrase – the subject matter content – and a verb or verb phrase – the cognitive process(es). Consider, for example, the following objective: The student shall be able to remember the law of supply and demand in economics.’ Here he points out that ‘the student shall be able to’, which is likely to be common to all objectives, can be ignored, leaving the verb ‘remember’, a cognitive process, and the noun phrase, ‘law of supply and demand in economics’, an element of knowledge.

The verbs and nouns that can be used to express desired learning outcomes, as exemplified on the Revised Taxonomy, reappear in lists of ‘teaching and learning language’ (see also Figure 1.1). In almost any secondary classroom we could expect to hear teachers giving instructions or invitations such as the following:

‘Could you define “botany”’?

‘Can you illustrate what is meant by a “deciduous tree”, and give an example?’

‘Explain why the French revolution happened when it did’.

‘Compare the causes of the Mexican revolution and the French revolution’, and so on.

Moreover, many of these verbs are also used in instructions in tests and textbooks and are likely to feature in talk between students when they are discussing learning tasks.

Classroom Language

In order to learn, students must use what they already know so as to give meaning to what the teacher presents to them. Speech makes available to reflection the processes by which they relate new knowledge to old. But this possibility depends on the social relationships, the communication system, which the teacher sets up. (Barnes in National Institute of Education, 1974: 1)

It was clear to both Vygotsky and Barnes that, if language is essential for thought and concept building from an early age, teaching (or ‘instruction’) involving speech, written texts and the use of other systems of signs must be key to children’s development and learning at later ages within the education system. A question that, we believe, is too seldom addressed in teacher education and teachers’ reflection on their work is: how can language be used most effectively in the sociocultural space of the classroom – or indeed outside the classroom – to stimulate genuine development and learning?

Since the 1970s and earlier, the role of classroom talk in learning has been the object of research and discussion within a fairly restricted circle of educationalists. In his research into and discussion of what he calls ‘learning by talking’, described in his book From Communication to Curriculum (Barnes, 1976), Barnes successfully demonstrated how exploratory talk within small groups of children in the classroom, for example about a poem, stimulates the ‘recoding’ and enhancement of their understanding in a way that would have been much harder for them to achieve on their own, or indeed with explanations or ‘telling’ from a teacher. But in so doing Barnes was addressing a far bigger issue, namely the way in which instruction and the type of language and communication that was – and still is – most often used by teachers to ‘transmit’ knowledge and concepts reaffirms the power structures in society that militate against autonomy, reflection and equal opportunities, including children’s opportunities for learning. By contrast, exploratory talk in the classroom, more recently termed ‘dialogic teaching’ by Robin Alexander (once a colleague of Barnes’s) (e.g. Alexander, 2008), moves away from the traditional transmissive routine that involves initiation by the teacher, response by a student or more than one, and evaluation or feedback by the teacher (IRE or IRF for short), and instead encourages genuine dialogue between the teacher and students, and among students, of a kind that helps them to interpret, reshape and recode concepts and ideas in their own individual ways and on their own terms.

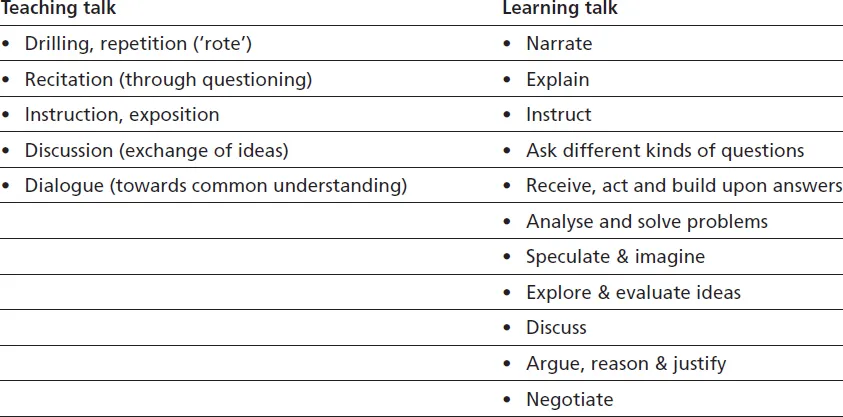

Based on analysis of teacher and learner talk during classroom research projects in the 1990s in five countries (England, France, India, Russia and the United States) and follow-up work in the UK, Alexander proposed the categories listed in Figure 1.1.

Figure 1.1 ‘Teaching talk’ and ‘learning talk’

Source: Adapted from Alexander (2008: 38–39)

As Alexander points out,

Only the last two of these [kinds of teaching talk] are likely to meet the criteria of dialogic teaching … and while we are not arguing that rote should disappear (for even the most elemental form of teaching has its place) we would certainly suggest that teaching which confines itself to the first three kinds of talk … is unlikely to offer the kinds of cognitive challenge which children need. (Alexander, 2008: 31)

However, for dialogic teaching to be successful, Alexander and his colleagues believe that teachers also need to work hard on helping children to develop their repertoire of the types of learning talk identified in Figure 1.1, as well as their ability to listen, to ‘be receptive to alternative viewpoints, think about what they hear, and to give others time to think’ (Alexander, 2008: 40).

Questioning

An area that does not feature prominently in Alexander’s list, but which others have written extensively about, is the way in which teachers use questioning. In their book aimed at the teaching profession, Norah Morgan and Juliana Saxton illustrated how different types of teacher questions at primary and secondary school level can relate to the categories proposed in the Taxonomy of Educational Objectives discussed earlier. These include, for example, questions that draw on knowledge, questions to test understanding, questions which require application, and questions which promote evaluation or judging (Morgan & Saxton, 1991: 12–15). However, they conclude that questions in teaching need to go beyond the Taxonomy because it does not in its original version deal with feelings (this is an issue which is addressed in Marzano’s New Taxonomy by introducing the so-called ‘self-system’ (Marzano & Kendall, 2007: 12–13)).

Morgan and Saxton propose a classification of teacher questions into three main groups: ‘questions which elicit information’; ‘questions which shape understanding’; and ‘questions which press for reflection’ (Morgan & Saxton, 1991: 41). It is particularly in the second and third of these groups that questions can address the dimensions that have a potentially key role to play in cognitive development.

Our own experience confirms this view of the role of communication and questioning in classrooms. However, the categories of learning talk and questions described above do not feature often enough in discussion of classroom interaction. Moreover, as Barnes and others have pointed out since the 1970s, focusing on the ways in which language and communication are used across the curriculum throws the spotlight on issues which are also important for teacher educators and teachers to reflect on:

• Where does power lie in classrooms and how is it shared?

• Who does most of the talking? The quite large group of students or the teacher?

• How productive is that talk? Is it more often in the form of IRF (which has its place), or does it sometimes involve genuine questions and dialogue?

• Are students from different backgrounds expected to learn in the same way, or is there allowance for different routes to learning?

• How successful is the classroom as a sociocultural space for a learning community where language is used to co-construct ideas and make cognitive progress?

Scaffolding

A concept that is often used when discussing teaching and learning talk, especially in subject teaching, is ‘scaffolding’. To fully understand the sense of this term we need to return to Vygotsky and a key concept defined by him: the ‘zone of proximal development’ (ZPD), which is,

the distance between the actual developmental level as determined by independent problem solving and the level of potential development as determined through problem solving under adult guidance or in collaboration with more capable peers. (Vygotsky, 1978: 86)

The implication of the ZPD is that a given stage in a child’s development opens up the potential for a next step in development, and that this next step needs to be aided in some way, for example, by a teacher (or a parent or another s...