- 656 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

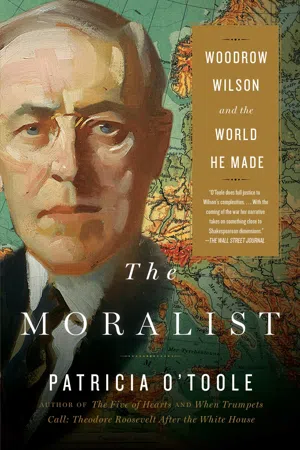

Acclaimed author Patricia O’Toole’s “superb” (The New York Times) account of Woodrow Wilson, one of the most high-minded, consequential, and controversial US presidents. A “gripping” (USA TODAY) biography, The Moralist is “an essential contribution to presidential history” (Booklist, starred review).

“In graceful prose and deep scholarship, Patricia O’Toole casts new light on the presidency of Woodrow Wilson” (Star Tribune, Minneapolis). The Moralist shows how Wilson was a progressive who enjoyed unprecedented success in leveling the economic playing field, but he was behind the times on racial equality and women’s suffrage. As a Southern boy during the Civil War, he knew the ravages of war, and as president he refused to lead the country into World War I until he was convinced that Germany posed a direct threat to the United States. Once committed, he was an admirable commander-in-chief, yet he also presided over the harshest suppression of political dissent in American history.

After the war Wilson became the world’s most ardent champion of liberal internationalism—a democratic new world order committed to peace, collective security, and free trade. With Wilson’s leadership, the governments at the Paris Peace Conference in 1919 founded the League of Nations, a federation of the world’s democracies. The creation of the League, Wilson’s last great triumph, was quickly followed by two crushing blows: a paralyzing stroke and the rejection of the treaty that would have allowed the United States to join the League. Ultimately, Wilson’s liberal internationalism was revived by Franklin D. Roosevelt and it has shaped American foreign relations—for better and worse—ever since.

A cautionary tale about the perils of moral vanity and American overreach in foreign affairs, The Moralist “does full justice to Wilson’s complexities” (The Wall Street Journal).

“In graceful prose and deep scholarship, Patricia O’Toole casts new light on the presidency of Woodrow Wilson” (Star Tribune, Minneapolis). The Moralist shows how Wilson was a progressive who enjoyed unprecedented success in leveling the economic playing field, but he was behind the times on racial equality and women’s suffrage. As a Southern boy during the Civil War, he knew the ravages of war, and as president he refused to lead the country into World War I until he was convinced that Germany posed a direct threat to the United States. Once committed, he was an admirable commander-in-chief, yet he also presided over the harshest suppression of political dissent in American history.

After the war Wilson became the world’s most ardent champion of liberal internationalism—a democratic new world order committed to peace, collective security, and free trade. With Wilson’s leadership, the governments at the Paris Peace Conference in 1919 founded the League of Nations, a federation of the world’s democracies. The creation of the League, Wilson’s last great triumph, was quickly followed by two crushing blows: a paralyzing stroke and the rejection of the treaty that would have allowed the United States to join the League. Ultimately, Wilson’s liberal internationalism was revived by Franklin D. Roosevelt and it has shaped American foreign relations—for better and worse—ever since.

A cautionary tale about the perils of moral vanity and American overreach in foreign affairs, The Moralist “does full justice to Wilson’s complexities” (The Wall Street Journal).

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

Son of the South

Thomas Woodrow Wilson entered the world in Staunton, Virginia, on December 28, 1856. His father, Joseph Ruggles Wilson, was a Presbyterian minister, and his mother, Jessie Woodrow Wilson, was the daughter of one Presbyterian divine and a descendant of several more. Tommy, as the baby was called, was their third child and first son. Before his second birthday, the family left Staunton for Augusta, Georgia, a move that put Joseph in a more prominent pulpit and brought him an honorary Doctor of Divinity degree.

In the autumn of 1860, Tommy was standing near the front gate of the Augusta parsonage when a passerby said that Abraham Lincoln had been elected and there would be war. Not yet four, the boy did not understand, but the force of the stranger’s voice sent him running into the house for an explanation. The war soon dominated the family’s life. After the national governing body of the Presbyterian Church declared its opposition to slavery, Joseph Wilson hosted the founding assembly of the Presbyterian Church in the Confederate States of America. He spent a summer as a chaplain to the Confederate Army, his churchyard occasionally served as a stockade for Union prisoners, and when necessary, a corner of the church was fitted out as a military hospital. Jessie assisted in caring for the wounded.

In 1870, when Tommy was thirteen, the family moved to Columbia, South Carolina, where Joseph joined the faculty of a Presbyterian seminary. Torched in the last weeks of the war, Columbia was still a blackened wreck. Although the adult Woodrow Wilson rarely reminisced about the destruction on view in Columbia, the ruins and the maimed soldiers he saw daily left him with a permanent horror of war.

Tommy grew up in the care of parents who were loving but not at ease in the larger world. Jessie was often abed with maladies that defied diagnosis, and Joseph, despite his eminence in Presbyterian circles, was hounded by a sense that he did not measure up. Shy except in the pulpit, he overcompensated by holding forth in schoolmaster fashion or by telling jokes, the same jokes, again and again. He was the sort of man who is more respected than enjoyed.

President Wilson’s moral certitude has often been ascribed to his religious upbringing, but Joseph Wilson’s Presbyterianism was not as exacting as the Scottish original. Joseph did not imagine that he knew the will of Heaven, nor did he tyrannize his congregations with visions of Hell. He savored at least two pleasures of the flesh, pipe smoking and Scotch drinking. In the furor loosed by Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species (1859), Joseph stood with the religious progressives who maintained that science was compatible with religion because all truths were part of a higher Truth.

Until the birth of the Wilsons’ fourth and last child, Joseph Jr., in 1867, Tommy was schooled by his parents, both of whom were intelligent, cultivated, and well educated. Joseph Sr. graduated at the head of his class at Jefferson College, in Canonsburg, Pennsylvania, and went on to study at two schools of theology. Jessie was a graduate of a respected school in Ohio, the Steubenville Female Seminary. The Wilsons prized moral education above other forms of instruction but also passed on their love of language and English literature. Joseph had a melodious, well-trained voice, and on Sunday afternoons, with the family gathered round, he entertained by reading a few chapters of Charles Dickens or Sir Walter Scott. Jessie had been born in England, but the Wilsons’ literary Anglophilia probably owed no more to that fact than to the educated American’s view of the Old World as the repository of high culture. The garden of American letters was still small, and to Southerners of the nineteenth century, it must have seemed choked with Yankees.

Tommy was odd man out in this bookish household. He did not learn the alphabet until he was nine, could not read until he was eleven or twelve, and at thirteen still struggled with reading and writing. Flagging every error in Tommy’s compositions, Joseph demanded revision after revision. It has been suggested that Tommy’s reading difficulties were the unconscious rebellion of a powerless boy against a powerful father, but it appears that Tommy’s reading problem was more physiological than oedipal. Edwin A. Weinstein, a neuropsychiatrist and close student of Wilson’s medical history, concluded that Wilson suffered from developmental dyslexia, a childhood disorder not understood at the time. Joseph suspected his son of laziness, a reasonable guess in light of the boy’s facility with spoken English. Tommy was precocious in conversation, had an exceptional ear for dialect, and was quick to master grammar and syntax. The adult Woodrow Wilson fondly recalled the hours he and Joseph had devoted to dissecting sermons and speeches to see how they worked and where they might be improved. No schooling would contribute more to Woodrow Wilson’s political triumphs than these oratorical studies.

If Woodrow Wilson ever wrote an unkind word about his father, it did not survive. The son voiced his admiration often and at length, and always referred to Joseph as the finest of all his teachers. Jessie rarely figured in Woodrow’s recollections, and the handful of stories that came down through the family suggest that she was humorless and touchy. Yet she must have been more than the sum of her faults. As a young man, Wilson freely confessed to having been a mama’s boy, and he and three other members of his extended family named daughters for her.

• • •

Tommy’s adolescence was a mix of escapist fantasy and small forays in the direction of independence. While physically present in his parents’ home, he led a covert parallel life in his imagination, first as Vice Admiral Thomas W. Wilson, who sailed the world, exterminated pirates, and recorded his exploits in dispatches to the Royal Navy. As Lieutenant Thomas W. Wilson of Her Majesty’s Royal Lance Guards, he upbraided subordinates for wearing civilian dress and warned that further infractions would bring a drop in rank. All his life, Woodrow Wilson felt himself in a tussle to control the side of his temperament he thought of as volcanic, and in his adolescent wish to command others, it is easy to see a wish to master his own unruly self.

At sixteen, Tommy hung a portrait of Prime Minister William Gladstone over his desk and announced that he too would be a statesman. The last of his invented selves, Commodore Wilson of the Royal United Kingdom Yacht Club, appeared shortly thereafter, and the commodore’s maritime preoccupations were soon crowded out by a consuming interest in writing the yacht club’s constitution. No longer content to rule his imaginary realms, Tommy yearned to organize them as well. The yearning, which became a lifelong passion, would culminate in his constitution for the world, the covenant of the League of Nations.

In spite of Tommy’s scholastic difficulties, his parents assumed that he would go to college, and his wish to be a politician rather than follow his father into the ministry drew a predictable reaction: Joseph sent him to Davidson College in North Carolina, a small Presbyterian establishment whose graduates typically went on to divinity school. Sixteen and now calling himself Tom, Wilson entered Davidson in 1873. He turned in a creditable academic performance and was an enthusiastic participant in a debating society. But in his second semester, when he suffered from an endless cold, his notebooks filled up with self-denigration, inspirational verse, and spiritual advice transcribed from Protestant periodicals.

Tom’s need for such solace coincided with the greatest crisis in his father’s life. In the spring of 1874, after years of success as a minister, church leader, and professor of theology, Joseph Wilson found himself out of work. He had clashed with his students over chapel attendance, the dispute went to the governing body of the church for adjudication, and when church authorities ruled in the students’ favor, Joseph resigned. The resignation was a matter of principle, he wrote Tom; the seminary had given him a responsibility but no power to carry it out. With a large household to support, Joseph hastily accepted a call from the Presbyterians of Wilmington, North Carolina. They offered a generous salary, but the church lacked the prestige of his posts in Columbia and Augusta, and Wilmington was regarded as a cultural backwater. Joseph was devastated.

Tom joined his family in Wilmington for the summer, expecting to return to Davidson in the fall, but it was soon decided that he would spend a year at home, studying Greek with a tutor to fit himself out for Princeton. Princeton appealed to Joseph because it was the finest Presbyterian college in the United States, and it appealed to Tom because it had produced an extraordinary number of statesmen. In the Republic’s first two decades alone, forty-three Princeton men had been elected to Congress (twenty-three to the House, twenty to the Senate), thirteen had become governors, and three had been appointed to the Supreme Court of the United States. The roll of honor also included a vice president (Aaron Burr) and a president (James Madison).

Tom worked at his Greek, and with the aid of mail-order instruction manuals spent hours mastering shorthand, a valuable skill for a boy who wrote slowly. He rarely socialized with his contemporaries during the fifteen months between Davidson and Princeton, and when he ventured out of the manse on his own, it was often to take a solitary walk around Wilmington’s harbor. To the Wilson family’s butler, the tall, quiet boy of eighteen seemed like “an old young man.” When not studying Greek or practicing shorthand, Tom spent long stretches of time with his father, and it is possible that Joseph’s crisis and his need for the companionship of his loving, much loved son were the chief reasons for the long interruption in Tom’s college education. Profoundly upset by his failure at the seminary, afraid that he would never again know success, Joseph suffered greatly yet refused to abandon his faith in God’s love. He grimly lashed himself to the mast and submitted to the will of Providence. Tom did not write about this time in their lives, but the experience of watching his father hold fast despite his anguish left an indelible impression. President Wilson would sometimes yield to expediency, but he never shrank from his deepest moral convictions, a trait that made him a formidable opponent and an unpredictable ally.

• • •

Tom set off for Princeton in September 1875, and apart from a brief detour into law, he would stay in academe until he entered politics, in 1910. After graduating from Princeton, he would study at the University of Virginia and Johns Hopkins, teach at Bryn Mawr and Wesleyan, and then return to Princeton for twelve years as a professor and eight as president. Each of these institutions suited him for a time, but Princeton was the only one he loved, and with good reason. His intellect, his passions, his political gifts—Princeton unfurled them all.

Soon after arriving, Tom met another statesman-in-waiting, Charles A. Talcott, who would serve a term in the U.S. House of Representatives when Wilson was president. As undergraduates, Wilson and Talcott vowed to groom themselves for politics by mastering all the arts of persuasion, especially oratory. Tom competed in campus debates, dissected great speeches, and took classic orations into the woods, where he could practice his delivery without being observed. He also labored over his compositions, honing his powers of argument and striving for the bright clarity he saw in the histories of Thomas Macaulay. Tom’s wish for a place in the governing class ran so deep that he sometimes fantasized himself already there. At a stalemate in a political tiff with one of his friends, he joshed that they would resume their debate in the Senate, and on a card that served as a bookmark, he signed himself “Thomas Woodrow Wilson, Senator from Virginia.”

Aware of Tom’s overreaching, Joseph occasionally reminded him of the need for patience and a sense of proportion. “Dearest boy, can you hope to jump into eminency all at once?” he inquired after Tom sent a petulant account of being passed over for an oratorical contest. “My darling, make more of your class studies. Dismiss ambition—and replace it with hard industry, which shall have little or no regard to present triumphs, but which will be all the time laying foundations for future work and wage.”

Unenthusiastic about most of his classes, Tom would finish thirty-eighth in a class of 105. But in history and philosophy, which abounded in lessons for would-be statesmen, he applied himself to excellent effect. Proudly he wrote his father, “I have made a discovery; I have found that I have a mind.” He also had a powerful will, although he could not force it to concentrate on mathematics or French or Greek. Instead he devoured works of English history and transcripts of debates in Parliament, which often appeared in the British press. An essay on oratory in one English periodical struck him with such force that he would always remember where he was when he read it—at the head of a staircase in the library. From his father Tom had learned that great oratory was closely reasoned and deeply felt as well as pleasing to the ear. The essay affirmed Joseph’s observations and went on to declare that great oratory was the fount of great statesmanship. Few notions could have ignited more hope in an aspiring politician who loved oratory and excelled at it.

As a Southerner, Tom often felt out of place at Princeton. He was stunned to find that his fellow students made no effort to conceal their contempt for the South, and when he failed in his attempts to broaden their minds, he wrote his mother that he sometimes longed to drive his arguments home with a punch. “Tommy dear, don’t talk about knocking anybody down—no matter what they do or say,” Jessie replied. “Yankee ignorance” must be borne in silence, she said, and in her experience, the less one said about politics, the better.

Tom kept his fists at his side but constantly thought, talked, and wrote about politics. In 1876, as the United States celebrated the centenary of the Declaration of Independence, he sourly predicted that the Republic would be destroyed by universal suffrage. Granted in 1870 by the Fifteenth Amendment, universal suffrage was hardly universal. It excluded women. But in giving the vote to all men, it threatened white supremacy in the South, where blacks outnumbered whites in many states. Many white Southerners, Tom Wilson included, argued that universal suffrage was a mistake not because blacks were black but because 80 percent of them were illiterate. That was true—a legacy of state laws that had made it a crime to teach slaves to read. But it was also true that 20 percent of whites were illiterate, and their fitness for the franchise was rarely challenged. Tom’s antipathy to universal suffrage was so strong that when he was asked to defend it in a campus debate, he declined.

Making friends came no more easily to Tom Wilson than to his parents, but a half-dozen classmates brought him into their circle, and once he was sure of their affection, he revealed that behind his decorous facade there was a great big ham. He loved theater and by osmosis had become a gifted mimic. His new friends were regularly entertained with impersonations, jokes told in several dialects, and a large store of limericks. His performances, like his father’s, masked his shyness, but he could summon more charm than his father. Tom’s friends reveled in his antics, admired his discipline, and encouraged his political ambitions. Several of them would energetically deploy their influence and wealth to speed his rise to prominence. The friends Wilson made at Princeton were the only friends he kept for life.

In his last year at Princeton, Wilson felt sufficiently sure of his literary and intellectual powers to submit a political essay to the International Review, a prestigious journal of opinion. Entitled “Cabinet Government in the United States,” the essay pointed out a deficiency in the American political system and proposed a remedy. Pressing national issues were being ignored, the author said, because senators and congressmen no longer engaged in serious public debate. Instea...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Dedication

- Epigraph

- List of Maps

- A Moralist in the White House

- 1. Son of the South

- 2. When a Man Comes to Himself

- 3. Ascent

- 4. Against All Odds

- 5. A New Freedom

- 6. A President Begins

- 7. Lines of Accommodation

- 8. Our Detached and Distant Situation

- 9. Moral Force

- 10. A Psychological Moment

- 11. Departures

- 12. The General Wreck

- 13. At Sea

- 14. Moonshine

- 15. Strict Accountability

- 16. Haven

- 17. Dodging Trouble

- 18. The World Is on Fire

- 19. Stumbling in the Dark

- 20. The Mystic Influence of the Stars and Stripes

- 21. By a Whisker

- 22. Verge of War

- 23. Decision

- 24. The Associate

- 25. The Right Men

- 26. One White-Hot Mass Instinct

- 27. Over Here, Over There

- 28. So Many Problems Per Diem

- 29. Defiance

- 30. Final Triumph

- 31. Storm Warning

- 32. The Fog of Peace

- 33. Settling the Accounts

- 34. Stroking the Cat the Wrong Way

- 35. Paralyzed

- 36. Altogether an Unfortunate Mess

- 37. Breaking the Heart of the World

- 38. Best of the Second-Raters

- 39. Swimming Upstream

- Epilogue: The Wilsonian Century

- Photographs

- Acknowledgments

- About the Author

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index

- Illustration Credits

- Copyright

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access The Moralist by Patricia O'Toole in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Political Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.