- 480 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

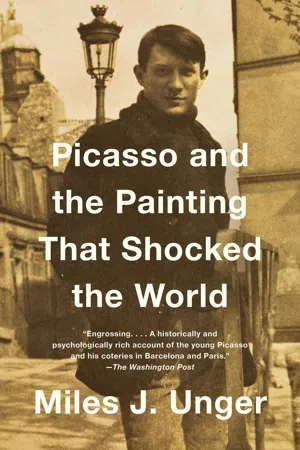

Picasso and the Painting That Shocked the World

About this book

One of The Christian Science Monitor’s Best Nonfiction Books of the Year

“An engrossing read…a historically and psychologically rich account of the young Picasso and his coteries in Barcelona and Paris” (The Washington Post) and how he achieved his breakthrough and revolutionized modern art through his masterpiece, Les Demoiselles d’Avignon.

In 1900, eighteen-year-old Pablo Picasso journeyed from Barcelona to Paris, the glittering capital of the art world. For the next several years he endured poverty and neglect before emerging as the leader of a bohemian band of painters, sculptors, and poets. Here he met his first true love and enjoyed his first taste of fame. Decades later Picasso would look back on these years as the happiest of his long life.

Recognition came first from the avant-garde, then from daring collectors like Leo and Gertrude Stein. In 1907, Picasso began the vast, disturbing masterpiece known as Les Demoiselles d’Avignon. Inspired by the painting of Paul Cézanne and the inventions of African and tribal sculpture, Picasso created a work that captured the disorienting experience of modernity itself. The painting proved so shocking that even his friends assumed he’d gone mad, but over the months and years it exerted an ever greater fascination on the most advanced painters and sculptors, ultimately laying the foundation for the most innovative century in the history of art.

In Picasso and the Painting That Shocked the World, Miles J. Unger “combines the personal story of Picasso’s early years in Paris—his friendships, his romances, his great ambition, his fears—with the larger story of modernism and the avant-garde” (The Christian Science Monitor). This is the story of an artistic genius with a singular creative gift. It is “riveting…This engrossing book chronicles with precision and enthusiasm a painting with lasting impact in today’s art world” (Publishers Weekly, starred review), all of it played out against the backdrop of the world’s most captivating city.

“An engrossing read…a historically and psychologically rich account of the young Picasso and his coteries in Barcelona and Paris” (The Washington Post) and how he achieved his breakthrough and revolutionized modern art through his masterpiece, Les Demoiselles d’Avignon.

In 1900, eighteen-year-old Pablo Picasso journeyed from Barcelona to Paris, the glittering capital of the art world. For the next several years he endured poverty and neglect before emerging as the leader of a bohemian band of painters, sculptors, and poets. Here he met his first true love and enjoyed his first taste of fame. Decades later Picasso would look back on these years as the happiest of his long life.

Recognition came first from the avant-garde, then from daring collectors like Leo and Gertrude Stein. In 1907, Picasso began the vast, disturbing masterpiece known as Les Demoiselles d’Avignon. Inspired by the painting of Paul Cézanne and the inventions of African and tribal sculpture, Picasso created a work that captured the disorienting experience of modernity itself. The painting proved so shocking that even his friends assumed he’d gone mad, but over the months and years it exerted an ever greater fascination on the most advanced painters and sculptors, ultimately laying the foundation for the most innovative century in the history of art.

In Picasso and the Painting That Shocked the World, Miles J. Unger “combines the personal story of Picasso’s early years in Paris—his friendships, his romances, his great ambition, his fears—with the larger story of modernism and the avant-garde” (The Christian Science Monitor). This is the story of an artistic genius with a singular creative gift. It is “riveting…This engrossing book chronicles with precision and enthusiasm a painting with lasting impact in today’s art world” (Publishers Weekly, starred review), all of it played out against the backdrop of the world’s most captivating city.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Picasso and the Painting That Shocked the World by Miles J. Unger in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Arte & Monografías de artistas. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

ArteSubtopic

Monografías de artistas

In Search of Lost Time

We will all return to the Bateau-Lavoir. We were never truly happy except there.

—PICASSO TO ANDRÉ SALMON, 1945

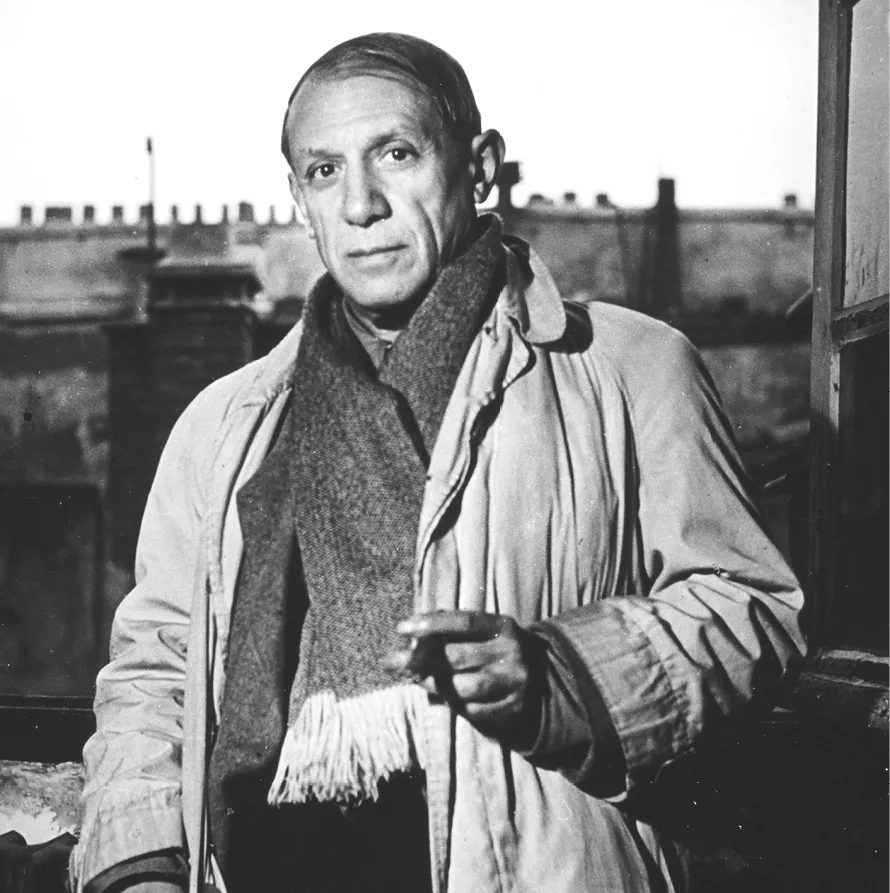

Pablo Picasso stood on the threshold of his apartment bundled against the autumn chill, his hat pulled low about his ears, a brown knit scarf tossed carelessly across his shoulders. A shapeless coat engulfed his stocky frame. Shabbily dressed, not so much anonymous as invisible beneath the layers, he hardly looked the part of the world’s most famous artist.

There was something incongruous in the scene, something about the man and the place that didn’t quite match. If the elegant address—a seventeenth-century apartment building on the rue des Grands-Augustins, in the genteel Left Bank neighborhood of Saint-Germain-des-Prés—proclaimed his worldly success, his rumpled outfit suggested an indifference to the trappings that came with it. With his stained pants, worn at the cuff, and felt cap “whose folds had long since given up the struggle for form,” Picasso showed the same disregard for convention he had as a struggling painter living from hand to mouth in a squalid Montmartre tenement. It was a quirk of his personality that his first wife had tried hard to correct. She often complained that no matter how much money he made, he insisted on dressing like a bum. In fact, the wealthier he became, the more determined he was that money would not define him. “One has to be able to afford luxury,” he once explained to the writer Jean Cocteau, “in order to be able to scorn it.”

Picasso in the rue des Grands-Augustins. © RMN-Grand Palais / Art Resource, NY.

In any case it was not his wife he was waiting for this Tuesday afternoon in the fall of 1945. Olga had long since fallen by the wayside, a casualty of her unsuccessful battle to groom him for a life in high society. For a time he’d submitted to her strict regime, attending costume balls hosted by the decadent Count Étienne de Beaumont, posing pipe in hand for the photographers, and generally playing the part of a debonair man-about-town. But he eventually tired of the cocktail parties and elegant soirees, reverting to the haphazard ways he’d enjoyed before the smart set claimed him as one of their own. The Hungarian photographer Brassaï, who met Picasso in 1932, was on hand to observe the process: “Those who thought that he had put his youth behind once and for all, forgotten the laughter and the farces of the early years, voluntarily abandoned his liberty and his pleasure in being with his friends, and allowed himself to be ‘duped’ by the pursuit of ‘status,’ found that they were mistaken. La vie de bohème regained the upper hand.” In truth, it had always been an unequal battle: while Olga tried to make him into a gentleman, he took revenge in his art by putting the former ballerina through a set of pictorial transformations, each more grotesque than the last.

Rather than Olga—or the voluptuous Marie-Thérèse Walter or the brooding Dora Maar, former mistresses who were both still part of Picasso’s extended harem—the woman he was expecting this afternoon was his latest conquest, the twenty-four-year-old, auburn-haired Françoise Gilot.

Perhaps conquest is not quite right. For once, it seemed, this relentless seducer had met his match. It’s true that after a strenuous campaign Françoise had agreed to share his bed, but his attempts to possess her body and soul had been frustrated by her infuriating streak of independence. Her ability to parry his advances only increased his determination to have her, but her inscrutable ways drove him to distraction. Brassaï testified to the “raw state of his nerves.” With Françoise, this usually self-confident man (particularly when it came to the war between the sexes) was reduced to a gelatinous state. “When I see Picasso, looking a little upset, shy as a college boy in love for the first time,” Brassaï recalled, “he gestures slightly toward Françoise, and says, ‘Isn’t she pretty. Don’t you think that she is beautiful?’ ”

Rue des Grands-Augustins. Courtesy of the author.

Françoise Gilot. © Ministère de la Culture / Médiathèque du Patrimoine, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Art Resource, NY.

There’s no doubt that Françoise Gilot—barely out of college and with little experience of the world in general, even less of men in particular—managed to throw him off balance. After more than a year of on-and-off wooing, Picasso was still unsure where he stood. “I don’t understand you,” he grumbled. “You’re too complicated for me.” In her most recent display of rebellion, Françoise had spent the last few months in the south of France, not exactly ending the relationship but making it clear that she wasn’t ready to commit to him. And when she finally returned, showing up unexpectedly on his doorstep, he couldn’t hide his hurt feelings. “I thought you weren’t coming back,” he sulked, “and that put me in a very black mood.” Though she was here now, Picasso knew she might just as easily slip away.

Since her return to Paris in late November, Picasso had assumed a role that had often worked before on star-struck young women, playing the older master to the eager pupil. Françoise had still not agreed to move in with him, but she visited his apartment almost every day. “Over the weeks that followed,” she recorded, “I began to do just what Pablo advised me to do: to study Cubism more in depth. In the course of my studies and reflections I worked back to its roots and even beyond them to his early days in Paris, between 1904 and 1909.” Being initiated into the mysteries of the twentieth century’s most important movement by its founder was a rare privilege for a budding artist, and Picasso was happy to oblige. These lessons drew them closer, their intimacy heightened by the sense of a shared voyage. At the same time they measured an unbridgeable gap: while she had her future in front of her, he belonged to history.

• • •

An older man—Picasso had turned sixty-four this past October—taking a young woman under his wing can generate a powerful sexual charge, and he was not above exploiting his fame to lure impressionable girls into his bed. But with Françoise it was different; he felt a kinship with her that went beyond mere sexual appetite. Each responded to the loneliness in the other, a sense of isolation that culminated in Picasso’s fantasy that his lover would live in the rafters beneath the rooftop of his studio where, together, they could shut out the world. When Jaime Sabartés—the childhood friend who now served as his personal secretary and gatekeeper at the rue des Grands-Augustins—warned him that the relationship was bound to end badly, Picasso turned on him angrily. “You mind your business, Sabartés,” Picasso shouted. “[W]hat you don’t understand is . . . the fact that I like this girl.” They were kindred spirits, he insisted, tormented souls who could find comfort only in each other’s arms.

Françoise was drawn to Picasso against her better judgment. Along with his famous charm, which he could turn on and off like a switch, he was bathed in the dazzling aura that surrounds all famous men. But there was more to his magnetism than this. Françoise was moved by Picasso’s vulnerability, a vulnerability that showed through the hard shell of mistrust that served to shut out a world that had wounded him. He could be arrogant, insufferable, too certain of his genius, and merciless to anyone he thought was preventing him from realizing his destiny. There was also a desperate neediness, a sadness that played on her maternal instincts, instilling an almost irresistible urge to fix what was wrong, to make whole what had been broken.

Still she held back, understanding instinctively that a relationship built around his all-consuming need was bound to be destructive. “I could admire him tremendously as an artist,” she remarked, “but I did not want to become his victim or martyr.”

• • •

Despite her youth, Gilot was no ingenue to satisfy the lust and prop up the vanity of an aging satyr (though as always in Picasso’s case those two most compelling of human motives were never completely absent). Indeed, when he’d spotted her two years earlier across the darkened room of his favorite restaurant, sitting with her childhood friend Geneviève, she’d been introduced to him as “the intelligent one” to distinguish her from her “beautiful” companion.

Of course, that was part of the problem. Françoise had a mind and a life of her own before she met Picasso. In May 1943 she had just made her professional debut with a show of paintings at the fashionable Madeleine Decré gallery (in sharp contrast to Picasso himself, who had been labeled “degenerate” by the Nazi occupiers and whose work was banned from public exhibition). Noticing the two attractive women in the company of an actor he knew, Picasso sauntered over to their table bearing a bowl of ripe cherries, a luxury in wartime Paris that carried more than a faint erotic whiff. When Geneviève told him that she and her friend were painters, he burst out laughing. “That’s the funniest thing I’ve heard all day,” he snorted. “Girls who look like that can’t be painters.”

Still, he’d been sufficiently intrigued to pay an incognito visit to the gallery, and the following week, when Françoise took him up on his invitation to visit him in his studio, he remarked, “You’re very gifted for drawing. . . . I think you should keep on working—hard—every day.”

Françoise was flattered by the great man’s attention, but she had few illusions as to the nature of his interest. At first Picasso opted for the direct approach. On one occasion he pulled her roughly to him and planted a kiss on her lips; on another, he casually cupped her breasts like “two peaches whose form and color had attracted him.” Assuming he was merely trying to provoke her, Françoise determined that the best way to knock him off his game was by failing to play the role of the outraged virtue he expected. “You do everything you can to make things difficult for me,” he complained, dropping his hands. “Couldn’t you at least pretend to be taken in, the way women usually do? If you don’t fall in with my subterfuges, how are we ever going to get together?”

When Françoise finally relented, then, it was with eyes open, and even after they became lovers she was careful to retain room for maneuver, rebuffing his increasingly urgent pleas that she move in and tormenting him with what he described as her “English reserve.”

Withholding a part of herself was an act of self-preservation. Françoise knew it was almost impossible to be intimate with Picasso without losing oneself entirely. Stronger women than she had been consumed in the furnace of his passion, an obsession whose intensity inevitably turned to disillusionment. “For me,” he told her, “there are only two kinds of women—goddesses and doormats.” The idol inevitably fell, the object of worship becoming the focus of rage when she failed to vanquish the demons that haunted him. After the end of the wartime occupation he became increasingly unpredictable, lashing out angrily or wallowing in self-pity as his growing celebrity increased his sense of isolation. “[H]e was very moody,” Françoise recalled, “one day brilliant sunshine, the next day thunder and lightning.”

For an older man, a consuming passion for an attractive woman young enough to be his granddaughter inevitably stirred up morbid thoughts of lost time, of the yawning chasm between his own vanished past, the inadequate present, and the uncertain future. As Picasso aged, the women he chose tended to get younger. His success in that arena reassured him that he retained the vital spirit that made him a force of nature, and any stumble conjured up the specter of his own mortality. In love, as in art, there were many pretenders to the throne, and if so far he had managed to stay on top, it remained a constant war against not only a host of rivals but also a more remorseless foe.

• • •

When Françoise arrived at the rue des Grands-Augustins that Tuesday afternoon, she was surprised to find Picasso already waiting on the front steps. Usually he kept an eye out for her seated at the second-floor window, one of his pet pigeons perched familiarly on his shoulder.

“I’m going to take you to see the Bateau Lavoir,” he announced, summoning like a talisman the name of the ramshackle tenement where he had spent his early years in Paris and where he had transformed himself from a young unknown to the acknowledged leader of the modern movement. “I have to go see an old friend from those days who lives near there.”

Before long, a car squeezed through the wrought-iron gate and inched into the courtyard, a jet black monstrosity—half hearse, half royal chariot—driven by a chauffer in white gloves and livery. This was Marcel at the wheel of Picasso’s famous Hispano Suiza Coupe de Ville. The car was a relic from the days before the war, one of the few reminders Picasso allowed himself of his life with Olga: a souvenir of Parisian seasons filled with society balls and summers on the Riviera with Ernest Hemingway and the Fitzgeralds. Among the anachronistic touches were multiple interior mirrors for making the final adjustments to one’s evening wear and crystal vases filled with cut flowers.

It was a strange possession for someone who called himself a Communist, as odd as the grand and gloomy apartment that recalled a vanished aristocracy of minuets and powdered wigs. Since his headline-making announcement the year before that he was joining the “People’s Party,” the chauffeured limousine had become something of an embarrassment, a visible symbol of hypocrisy. But for Picasso (who never learned to drive) the car was more than a luxury. It was a means of escape when the routines and the people associated with a particular place grew too burdensome. During the war years, with gasoline rationed and movement restricted by the Germans, he’d been forced to abandon his peripatetic ways. Now, after years of claustrophobia and paranoia, he could once again travel at will, a necessary balm for his restless soul.

The restlessness had always been there, but his kinetic energy used to take a different form. As a young man he had prowled Paris on foot, feeding his inspiration by feeding off the excitement of the vibrant city, wearing holes in shoes he couldn’t afford to mend. It was not simply the last resort of a poor man; walking was a form of epistemology, a way of knowing. It provided the essential textures and materials of his art. The woman who lived with Picasso during his years of poverty remarked, “[I]t is good to walk when you are young and carry hope in your heart.” In meandering journeys through the neighborhoods of his adopted city he had time to think, to tease out the tangled skeins of his vision and explore new vistas and uncharted alleyways of the mind. And while he wandered, he absorbed the sights and smells of the great capital, its hectic rhythms so different from those of his native Spain, its jarring dislocations and cacophony finding their way in the fractured surfaces of his canvases. Now his face was plastered on magazine covers on every corner newsstand, and as the world crowded in, he withdrew, increasingly alienated, unmoored.

With Marcel at the wheel, Picasso and Françoise watched the city unspool in silence, the noise and dust shut o...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Dedication

- 1. In Search of Lost Time

- 2. The Legendary Hero

- 3. Dirty Arcadia

- 4. Les Misérables

- 5. The Square of the Fourth Dimension

- 6. La Vie en Rose

- 7. Friends and Enemies

- 8. The Village Above the Clouds

- 9. The Chief

- 10. Exorcism

- 11. Drinking Kerosene, Spitting Fire

- 12. Bohemia’s Last Stand

- Photographs

- Acknowledgments

- About the Author

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index

- Copyright