eBook - ePub

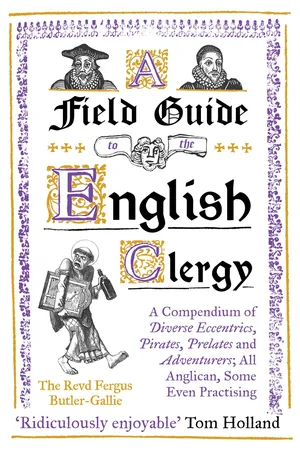

A Field Guide to the English Clergy

A Compendium of Diverse Eccentrics, Pirates, Prelates and Adventurers; All Anglican, Some Even Practising

- 192 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

A Field Guide to the English Clergy

A Compendium of Diverse Eccentrics, Pirates, Prelates and Adventurers; All Anglican, Some Even Practising

About this book

‘Ridiculously enjoyable’ Tom Holland

A Book of the Year for The Times, Mail on Sunday and BBC History Magazine

The ‘Mermaid of Morwenstow’ excommunicated a cat for mousing on a Sunday. When he was late for a service, Bishop Lancelot Fleming commandeered a Navy helicopter. ‘Mad Jack’ swapped his surplice for leopard skin and insisted on being carried around in a coffin. And then there was the man who, like Noah’s evil twin, tried to eat one of each of God’s creatures…

In spite of all this they saw the church as their true calling. These portraits reveal the Anglican church in all its colourful madness.

A Book of the Year for The Times, Mail on Sunday and BBC History Magazine

The ‘Mermaid of Morwenstow’ excommunicated a cat for mousing on a Sunday. When he was late for a service, Bishop Lancelot Fleming commandeered a Navy helicopter. ‘Mad Jack’ swapped his surplice for leopard skin and insisted on being carried around in a coffin. And then there was the man who, like Noah’s evil twin, tried to eat one of each of God’s creatures…

In spite of all this they saw the church as their true calling. These portraits reveal the Anglican church in all its colourful madness.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access A Field Guide to the English Clergy by The Revd Fergus Butler-Gallie in PDF and/or ePUB format. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Publisher

Oneworld PublicationsYear

2018eBook ISBN

9781786074423Subtopic

Biographies religieuses

PRODIGAL SONS

The figures in this section are neither hardnosed bruisers who fought their way to prominence, but nor are they necessarily meek and mild. However, whether as a result of rising through the ranks of the Church as Bishops or Archbishops, becoming the most renowned wit of their day, accidentally being acclaimed as a sporting icon or, through quiet heroism, saving thousands of lives, each could be considered a ‘success’ in one way or another. They can all be considered ‘Prodigal Sons’; figures who, like the son in the parable in St Luke’s Gospel, ended up fêted against the odds. Very often their circumstances, early lives or personalities were less than auspicious and yet, in the end, they found themselves celebrated for one reason or another. In some cases their prodigal status manifested itself in terms of professional preferment or administrative efficiency despite manifest oddity or disinterest, but in others it has been necessary to defer to the old adage vox populi, vox Dei. Congregations are, after all, the people who see clergy week in week out; if they can’t tell clerical saint from sinner, then no one can.

As befits biographies of those who all (ostensibly) believed in the Resurrection, no distinction is made between success in life and success post-mortem – while some climbed the dizzy heights of the ecclesiastical hierarchy, several of these clergy departed this life forgotten, only for their impact to become clear later. They were all individuals who, in any other career, would have been disastrous; indeed, in a secular context many would be considered unemployable. From their idleness to their inappropriate comments, their strange habits to their downright stubbornness, these are men who would, according to conventional wisdom, be considered weak and foolish in equal measure. And yet, for all their failings, they all made their mark on the world – some in ways that affected millions, others through just one life changed for the better.

Regrettably, the leading clergy of today no longer aspire to win the Polar Medal, blame social democracy for weak tea or shout ‘BALDOCK’ at random intervals.

They are engaged in chairing meetings, managing figures and studying for MBAs. Typically, just as the reputation of corporate jargon and practice reaches its lowest ebb in the secular world, the Church of England has sought to embrace it with open arms. As such, unlikely as these successes might have seemed in the past, they would be nigh on impossible now. Political changes in the last few decades mean that the Church now appoints its own senior figures without input from anyone else. As a consequence, the generations of lunatics, curmudgeons and visionaries inflicted on the Church in either strokes of bureaucratic genius or as the result of elaborate civil service jokes have, regrettably, come to an end.

There will always be eccentrics, rogues, bon viveurs and bizarre intellectuals among the clergy, but it is difficult to see a future for the brave and brilliant, but often irascible or insane individuals of the sort detailed in this section. They have been sacrificed to the idol of earnestness, to the cult of taking-things-seriously. The result of this is not that the Church has won back some great lost dignity but, by fearing the difficult or eccentric, has diminished her pool of talent and made herself seem less human, ironically rendering the institution even more ridiculous than before. It is always sensible to remember, dear reader, that God (like many of the characters described in the following pages) does appear to have a sense of humour after all.

I

The Most Reverend and Right Honourable

Michael Ramsey, Archbishop of Canterbury and

Primate of All England (1904–88)

Michael Ramsey, Archbishop of Canterbury and

Primate of All England (1904–88)

‘He is totally unsuitable to be Archbishop of Canterbury’

One evening during the spring of 1961, a short figure in a thick black overcoat, seemingly oblivious to the unseasonably warm weather, climbed up the steps of Admiralty Arch on the Mall. The man was Geoffrey Fisher, the weary outgoing Archbishop of Canterbury. Fisher had become Prelate during the dying days of the Second World War after the government’s first choice to lead the Church of England into the brave new postwar world, William Temple, dropped dead after barely two years on the job. By the start of the swinging sixties, Fisher was increasingly worn down by life and cynical about the future; when asked his views on nuclear proliferation he replied laconically that ‘the worst the bomb can do is sweep a large number of people from this world into the one they must eventually go to anyway’.

Fisher used to meet with the prime minister, Harold Macmillan, who was living temporarily in a cramped flat in Admiralty Arch while Downing Street was being refurbished. Macmillan dreaded his meetings with Fisher, complaining that ‘whilst I always want to talk about religion the Archbishop will insist on talking politics’. Fisher announced his intention to resign as Archbishop and, unable to suppress the inner school teacher (he had run Repton School prior to being a Bishop), decided to offer Macmillan some advice on his successor. ‘Whomever you choose,’ Fisher began in his most authoritative tone, ‘it must not be the Archbishop of York. He is a theologian, a scholar and a man of prayer. And he is totally unsuitable to be Archbishop of Canterbury. I would know – I was his headmaster.’ Macmillan smiled and with the sort of imperturbability for which he was to become famous said, ‘Thank you, your Grace, for your kind advice. However, whilst you may have been Dr Ramsey’s headmaster, you were not mine.’ He duly appointed Michael Ramsey as Archbishop.

To be fair to Fisher, Ramsey was not the obvious choice. The child of a socialist and a suffragette, he had been a Congregationalist until his twenties and had a brother who, until his tragic early death, was Britain’s most prominent atheist. On top of these unlikely origins, Ramsey was noted for having somewhat strange habits. As a child he used to spend hours careering round his parents’ house trying to touch every wall in as quick succession as possible, and he used to enrage fellow students at theological college by spending chapel services tearing his handkerchiefs into strips. His tics could be verbal as well as physical. One young clergyman who had been enlisted to drive Ramsey from London back to Cambridge when he was a professor there in the 1950s recalled how, when they happened to pass through the Hertfordshire village of Baldock, Ramsey was so taken with the name of this unassuming market town that he spent the rest of the journey bellowing it out of the car window at the top of his voice.

At times he was just plain forgetful – such as when he locked a group of American airmen in Durham Cathedral as a Canon there during the war. Ramsey was supposed to be giving them a tour but got separated, forgot why he was there and decided to lock up as usual, leaving the men from Milwaukee to spend a chilly night huddled around the tomb of St Cuthbert. A number of behavioural experts have tried retrospectively to diagnose Ramsey, with conclusions varying from a mild form of attention deficit disorder to some form of autism. Regardless of the reasons behind Ramsey’s behaviour, his manifest eccentricities meant that he was an unusual choice as the hundredth occupant of the throne of St Augustine.

While certain aspects of the job challenged him (visits to Sandringham were, for instance, dreaded by both the Royal Family and the Archbishop himself because of Ramsey’s inability to keep still or make small talk), in other areas he proved himself more than equal to the task of leadership. The strength of his support for decriminalising homosexuality probably carried the bill through the House of Lords, and his rigorous opposition to apartheid in South Africa enabled the Anglican Church there to take a leading role in attempts to dismantle the system of white minority rule. He could also show flashes of wit – when asked by an eager cleric, looking for approval for an academic project, whether a comprehensive dictionary of heresies existed, he replied, ‘Of course it exists, it’s called Hymns Ancient and Modern.’ Eventually, the constant battle to be understood and to lead the unwieldy Church became too much – it was said that by 1974 he would start each day by bashing his head on his desk three times and repeating the mantra ‘I hate the Church of England’ before he could bear to open his correspondence. Perhaps unsurprisingly, Ramsey resigned later that year.

Retirement, however, only caused the plot to thicken. Ramsey moved to Durham where, in 2009, some two decades after his death, a strange series of discoveries were made in the River Wear near the Archbishop’s retirement home. A pair of amateur divers found a large number of gold and silver coins, medals and crucifixes near where the river flows past the cathedral close. Any hopes of an Anglo-Saxon hoard quickly dissipated when they were all found to be linked to key events Ramsey had attended – from a medallion commemorating his opening of a church in India to a crucifix thought to have been presented to the Archbishop by Pope Paul VI. The scattering of the items suggested that they had actually been thrown in over a period of some years. As always with Ramsey, this seeming eccentricity has a somewhat endearing reason behind it. Ramsey found he had far too many possessions to fit into his Durham house as he downsized from Lambeth Palace. He had tried selling some items in aid of charity, but this had caused such offence to those who had originally given them to him that, in order to avoid further embarrassment, the perpetually shy Ramsey elected to chuck them into the icy waters of the Wear instead. As the reasons behind the bizarre watery fate of the objects became clear, an old friend is said to have chuckled knowingly and simply remarked: ‘That is so Michael Ramsey’.

II

The Right Reverend Launcelot Fleming,

Bishop of Norwich (1906–1990)

Bishop of Norwich (1906–1990)

Helicopters and Heroism: The Unlikely Career

of the ‘Space Bishop’

of the ‘Space Bishop’

Of all the clergy in this volume, Bishop Launcelot Fleming is arguably the most difficult to categorise; not because he is unexceptional but, rather, because he was a figure who displayed an abundance of distinguishing features. He was an impressive academic and a thoroughgoing eccentric; a brave adventurer and a famous bon viveur. Fleming, the son of a Scottish doctor, was indubitably bright. His childhood passion for geology led him to study the subject at both Cambridge and Yale, but, to the surprise of some contemporaries, he eschewed a career as a professional geologist and opted to take Holy Orders instead.

Fleming was ordained in 1934 and, rather than becoming a Curate somewhere like most clergy (Fleming was, as we shall see, not one for convention), immediately became Chaplain of his old college, Trinity Hall, where he spent exactly one week in the post before taking a year out on sabbatical in order to accompany an expedition to the island of Spitsbergen in the Arctic Circle. During his absence Trinity Hall decided, as only a Cambridge college can, to promote Fleming to the crucial role of Dean (he would have been in Svalbard at the time). As with the post of Chaplain, the Dean’s position was not a job that Fleming bothered spending too long getting to know about: it was a matter of months before Fleming had left Cambridge again in favour of Antarctica. Fleming was not, however, merely an amateur; his contribution to the British Antarctic Expedition was considered so significant that, on his return in 1937, he was awarded the Polar Medal by King George VI for his bravery and research.

The Second World War somewhat interrupted Fleming’s Antarctic exploits. However, the fighting afforded him plenty of new avenues for adventure and, in 1940, he became a Royal Navy Chaplain. Fleming spent the war patrolling the Mediterranean and, despite being on board HMS Queen Elizabeth when she struck a mine, seems to have thoroughly enjoyed himself. He was of practical as well as spiritual use onboard – his small, wiry frame made him the perfect size for cleaning the ship’s guns, which was achieved by wrapping the Chaplain in a large cloth then hauling him through the barrel. After ‘a good war’ Fleming was expecting to return to a long, quiet career studying glaciers in Cambridge (he was invited, in 1946, to become Director of the Scott Polar Institute). What he, and probably much of the Church of England, was not expecting was that he would be made a Bishop.

However, in 1949 that is exactly what happened. Fleming was initially reluctant, but Portsmouth had such close links to the navy that he found it impossible to resist. Despite having been ordained for fifteen years, his ministry had mostly been confined to Cambridge colleges, warships and the continent of Antarctica; Fleming was now in charge of 150 parishes, despite never having set foot in one. On his first day in the job he had to have the concept of a Parochial Church Council (your basic church committee) laboriously explained to him and it soon became clear that his intention was to delegate almost everything to his Archdeacons. Against the odds, Fleming’s unorthodox approach appeared to have worked again with Portsmouth becoming so well run that, ten years after arriving there, the reluctant Bishop was on the move again, this time promoted to the diocese of Norwich.

Fleming’s extreme delegation meant that he had a great deal of time for his other interests. He spent prolonged periods visiting the naval base while at Portsmouth. He enjoyed his long conversations with sailors and officers so much that he would routinely overrun and be late for other meetings. The affection was clearly mutual as, when Fleming realised the time, they often dropped him off in one of the naval helicopters. This particular favour earned the Bishop a stern ticking off from First Sea Lord Louis Mountbatten when Fleming used a naval helicopter to fly all the way to Lambeth Palace to avoid being late for a meeting with the Archbishop of Canterbury. Beyond the navy, Fleming found other japes to occupy his time: he sought out a suitable railway on which to fulfil his lifelong dream of riding on the footplate of a train, which he managed in 1960; he also became the only Bishop in modern times to single-handedly pilot a bill through parliament (a bill indicating British acceptance of the Antarctic Treaty of 1959, which is still in force today).

Fleming’s unique approach to his duties meant he also found time to continue the flourishing social life that he had enjoyed in Cambridge. He was a member of numerous societies and dining clubs and was much in demand as a dinner companion. It was on his return from a well-lubricated meeting of one such dining club in 1962 that Fleming met the woman who would become his wife. Fleming had been out with the ‘Nobody’s Friends’ club, a group of High Church clergy with famously large appetites for both food and wine. The little Bishop of Norwich had done his best to keep up but, by the time he arrived back at the London house of the friends with whom he was staying, he was a little worse for wear. Somewhere on his journey back, Fleming had picked up and put on a motorbike helmet. When one Jane Agutter came downstairs after hearing a mighty crash, she found the Bishop wandering down the hallway in his new headgear singing ‘I’m a space Bishop’ in a cod-liturgical voice. Quite why this made such an impression on Jane we’ll never know but, three years later, when Fleming was fifty-eight, she agreed to marry him.

Fleming remained active into his advancing years. It was a particular tragedy for him, therefore, when he was struck down with a rare spinal disorder during his time at Norwich, making mobility difficult. He had always been popular with the Royal Family and so, in 1970, he resigned his see and moved to become Dean of Windsor. The gentler pace of life suited him, even if the bickering of the chapel’s Canons did not. Eventually old age did what hypothermia and German mines could not and, in 1990, Fleming died peacefully at home with his medals and his wife (although not his motorcycle helmet) at his side.

III

Canon Sydney Smith,

Canon of St Paul’s Cathedral (1771–1845)

Canon of St Paul’s Cathedral (1771–1845)

‘His jokes were sermons and his sermons jokes’

Sydney Smith was something of a legend in his own time. Renowned as ‘the Smithiest of Smiths and the Wittiest of Wits’, people travelled from all over the country – indeed, all over the world – to hear Smith hold forth on various subjects. From sharp one-liners to whole evenings taking centre stage as a raconteur, Smith was Regency England’s top stand-up comedian. He was also, from 1796, a clergyman in the Church of England. The combination of this most serious of jobs with this least serious of men should not, according to received wisdom, have worked, but Smith was one of a kind.

Smith’s talent for words was spotted early on. He was a schoolboy at Winchester College where, dismayed at the absolute dominance of Sydney and his brother at annual prize-giving, the other pupils signed a petition and refused to enter any more exams if the Smiths were also sitting them. He continued to excel at Oxford and, after being made a Deacon in 1796, went to Edinburgh to continue his studies. His relationship with Scotland was a mixed one – he described it as ‘a land of Calvin, oatcakes, and sulphur’ – but, as well as being where he met his wife, it was also the place he first found fame. While he was supposed to be studying, Smith became renowned as a preacher, as a dinner party guest and as the editor of the Edinburgh...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Contents

- Eccentrics

- Nutty Professors

- Bon Viveurs

- Prodigal Sons

- Rogues

- A Glossary

- Appendix

- Copyright