eBook - ePub

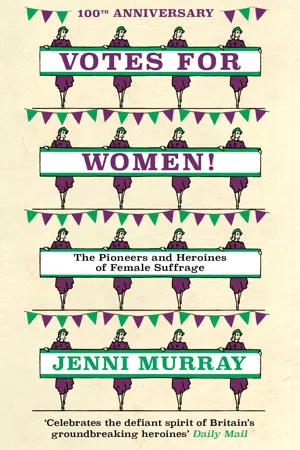

Votes For Women!

The Pioneers and Heroines of Female Suffrage (from the pages of A History of Britain in 21 Women)

- 144 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Votes For Women!

The Pioneers and Heroines of Female Suffrage (from the pages of A History of Britain in 21 Women)

About this book

Mary Wollstonecraft, Elizabeth Garrett Anderson, Millicent Fawcett, Emmeline Pankhurst, Constance Markievicz, Nancy Astor

They terrorised the establishment.

They fought for the vote.

They pushed back boundaries and revolutionised our world.

For the hundredth anniversary of the historic moment the franchise was finally extended to women, here is a selection of suffragette and suffragist activists and pioneering MPs from the pages of Jenni Murray’s bestselling A History of Britain in 21 Women. Set against the backdrop of a world where equality is still to be achieved, it is a vital reminder of the great women who fought for change.

They terrorised the establishment.

They fought for the vote.

They pushed back boundaries and revolutionised our world.

For the hundredth anniversary of the historic moment the franchise was finally extended to women, here is a selection of suffragette and suffragist activists and pioneering MPs from the pages of Jenni Murray’s bestselling A History of Britain in 21 Women. Set against the backdrop of a world where equality is still to be achieved, it is a vital reminder of the great women who fought for change.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Votes For Women! by Jenni Murray in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Historical Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

4

Emmeline Pankhurst

1858–1929

It’s Emmeline Pankhurst’s name that has long been most closely associated with the campaign for votes for women, although, I hope, after the preceding chapter on Millicent Garrett Fawcett, it will become clear that it was both the peaceful and persuasive suffragist movement combined with the militant, publicity-conscious tactics of Pankhurst’s suffragettes that made the cause impossible to ignore.

Emmeline Pankhurst was born in Sloane Street in Moss Side, Manchester to Robert Goulden, who owned a calico printing and bleach works, and his wife, Sophia Jane Craine. I’ve always found it deliciously ironic that her mother was born on the Isle of Man. Emmeline was the eldest of ten children and, from an early age, had to do her bit to care for her younger siblings.

She was educated at home, learned to read when she was very young and it was her job to read the daily paper to her father while he ate his breakfast. An interest in politics was thus fostered at the table. Family history also taught her that protest was a necessary part of politics if you felt something passionately. Her paternal grandfather had taken part in the Peterloo demonstration for parliamentary reform and universal suffrage in 1819. A huge crowd of demonstrators gathered peacefully in what’s now St Peter’s Square in Manchester – between sixty and eighty thousand – and were set upon by a cavalry charge. Sabres were drawn and civilian blood shed in a defining moment of British history. The number killed is not altogether clear. Some sources say fifteen, others eighteen, but it’s agreed that at least one woman and a child were among them. Some were killed by sabres, others by clubs or by being trampled to death by the horses. Some seven hundred lay injured. It became known as the Peterloo Massacre and so shocked a local businessman, John Edward Taylor, that he went on to help set up the Manchester Guardian newspaper. Mr Goulden senior was said to have narrowly missed death.

Emmeline’s brothers called her ‘the dictionary’ because she had such a command of the English language. She spoke well, wrote well and they envied her perfect spelling. She is said to have been in bed one night, pretending to be asleep, when she heard her father say, ‘What a pity she wasn’t born a lad.’

She had learned for herself that girls’ education was considered less important than that of boys when she was sent with her sister to a middle-class girls’ school. She was appalled when she found little emphasis on reading, writing, arithmetic or any kind of intellectual pursuit there. A lot of her lessons were devoted to learning how to be the perfect housewife, making a home comfortable for a man. In her ghostwritten autobiography, My Story, published in 1914, she said, ‘It was made quite clear that men considered themselves superior to women, and that women apparently acquiesced in that belief.’

When Emmeline began to be involved in active sexual politics she described herself as a ‘conscious and confirmed suffragist’. She had been made aware, from when she was tiny, of the meaning of slavery and emancipation. When she was five she had been asked by her parents to collect pennies in a ‘lucky bag’ for the newly emancipated slaves in the United States. Both her parents were supporters of equal suffrage and Sophia Jane took the monthly Woman’s Suffrage Journal, edited by Lydia Becker, one of Manchester’s foremost suffragists. When Emmeline was fourteen she asked her mother to take her to a meeting where Becker was speaking – she found the speaker’s ideas most engaging.

It was around this time, in late 1872, that Emmeline was sent to study in Paris. Her closest friend was a girl whose father was a famous republican who was imprisoned in New Caledonia for his part in the Paris Commune. Emmeline became a confirmed Francophile and found his story and Thomas Carlyle’s popular book The French Revolution an inspiration throughout her life. Carlyle’s work seems to revel in the violence of the revolutionary terror and welcomes the destruction of the old order in French society. Emmeline would never go so far as to advocate the guillotine for those who opposed her; indeed her suffragettes would be encouraged to damage property without harming human life, but she had learned that change can be achieved by violent revolution.

When she returned to Manchester from France she was almost nineteen and expected by her mother to fall in line in the way a respectable young lady should. Emmeline was not one to waste her energies on boring household tasks and made her view plain to her mother on numerous occasions. There were constant rows between the two women, best illustrated by the afternoon when Mrs Goulden demanded that her daughter should go and fetch her brother’s slippers and help make him comfortable. ‘No way,’ was Emmeline’s response. ‘If he wants his slippers he can go and get them himself. As for you, mother, if, as you claim, you are truly in favour of women’s rights, you are certainly not showing it at home.’

Emmeline began to work with the women’s suffrage movement and met a man who was a well-known radical lawyer and supporter of the women’s cause. He was Dr Richard Marsden Pankhurst and, despite the twenty-year age gap, they fell in love and married in 1879.

Their four children, Christabel, Sylvia, Henry Francis (known as Frank) and Adela, were born in the first six years of their marriage and while Emmeline’s involvement in public affairs was slowed down by motherhood, it far from stopped. In 1880 she was elected onto the committee of the Manchester National Society for Women’s Suffrage and was asked to join the Married Women’s Property Committee. She and her husband worked together closely on these committees and she campaigned twice on his behalf in 1883 and 1885 when he stood as an independent parliamentary candidate. They proposed the abolition of the House of Lords and the monarchy, adult suffrage on equal terms for both sexes, the disestablishment of the Church of England, nationalisation of land and Home Rule for Ireland. Pretty radical stuff! Pankhurst was not elected.

In 1886 the family left Manchester for London and set up home in Hampstead Road. Emmeline was keen to have financial independence and to support her husband materially so that he could concentrate on his politics, so she opened a shop selling fancy goods. There were frequent trips to Manchester on political business and it was during one of those visits that four-year-old Frank fell ill. When the parents arrived home he was critical. He had been wrongly diagnosed with croup, which turned out to be diphtheria, and he died in September 1888.

The cause of his illness may have been faulty drainage at the rear of the house in Hampstead, so the family closed the shop and moved to a rented house at 8 Russell Square. It was there that her fifth child was born. He was also called Henry Francis in memory of his older brother, but was known as Harry.

8 Russell Square became a centre for radical politics where Fabians – members of the Fabian Society, Britain’s oldest political think tank, founded in 1884 to develop public policy on the left – anarchists, socialists and suffragists would meet. The Pankhursts developed a close friendship with the Scottish socialist Keir Hardie, who was elected to Parliament as an Independent MP for West Ham South in 1892. He helped form the Independent Labour Party (ILP) the following year and in 1900 the Labour Party was born. Hardie was the first Labour Member of Parliament when he was elected that year as the junior member for the dual-member constituency of Merthyr Tydfil and Aberdare. He would represent the constituency for the rest of his life.

In 1893 the Pankhurst family went back to Manchester to 4 Buckingham Crescent. Emmeline resigned from the Women’s Liberal Association to join the ILP and in 1894 she was elected as an ILP member to the Chorlton Board of Guardians. The work involved the inspection of workhouses and she was often horrified by the terrible conditions she found there, particularly where girls and single women with babies were concerned. She was described as compassionate and fearless, and managed to introduce a number of improvements.

Her first brush with the law came in 1896 when some of her fellow members of the ILP were sent to prison for giving political speeches in the open air at Boggart Hole Clough, a large urban park, which was owned by Manchester City Council. The Pankhursts and their children were all involved in speaking out in defence of free speech, often appearing in the Clough, and she would shout that she was prepared to go to prison herself. She was taken to court but the case against her was dismissed. Confronted by such opposition to her beliefs, and to her right to speak in public, Emmeline’s association with the ILP grew even stronger. In 1897 she was elected to the party’s National Administrative Council.

The following year her beloved husband died suddenly as a result of stomach ulcers. He was only sixty-two. His legal practice had never made much money because his close association with the socialist movement had made him an unpopular choice for a great many potential clients. Emmeline and the children were left to struggle financially, and she refused any charitable help from political friends and associates. Instead she asked that donations should be made to build a hall in her husband’s memory in Salford.

Meanwhile, she moved the family to cheaper accommodation in 62 Nelson Street, which is now the home of the Pankhurst Centre, a small museum celebrating the birth of the suffragette movement. There was another failed attempt at opening a shop to earn money to keep the family from poverty and finally Emmeline accepted a salaried post as registrar of births and deaths in Chorlton. This work brought her into contact with working-class women who had come to register the births of their babies. They were often young, unmarried girls who had been abused by relatives or employers, and her determination that women must improve their position in society grew ever stronger.

It was five years after Richard’s death that the Pankhurst Hall in Salford was finally opened as the headquarters for the local branch of the ILP. Only one problem. It had been decided that women would not be allowed to join the party there. Emmeline immediately left the ILP in protest at what she saw as a waste of her commitment and time to the socialist movement. She became convinced that the only solution for women was to found their own political party.

In her autobiography she wrote, ‘It was in October, 1903, that I invited a number of women to my house in Nelson Street, Manchester, for the purposes of organisation. We voted to call our new society the Women’s Social and Political Union.’ It was agreed the organisation would be open to women of any class and its focus would be a campaign to win votes for women, with the motto ‘Deeds not Words’. A few years later, in 1908, the WSPU adopted a colour scheme of purple, white and green, symbolising dignity, purity and hope.

The suffragettes were, from the beginning, adept at publicity and self-promotion, understanding the need for a slogan and an identifiable colour scheme. Money would be raised from the sale of scarves and hats in suffragette colours, and from postcards and booklets whose sense of humour often matched those of the Punch cartoons, but told the other side of the woman question. The suffragettes clearly showed the positive side of the emancipation of women, whereas the Punch cartoonists invariably portrayed it as a potential disaster for hearth and home.

The first notable campaign carried out by the WSPU, after a number of peaceful appearances at trade unions’ conferences and street demonstrations, came in the autumn of 1905 on the eve of a general election, when it was expected the Liberals would win. Emmeline’s oldest daughter, Christabel, and Annie Kenney, a working-class Manchester woman, went to a Liberal Party meeting at the Free Trade Hall (now a posh hotel) and asked a question: ‘Will the Liberal government, if returned, give votes to women?’ No one answered their question, so they asked it again. They were bundled out of the hall, charged with obstruction and sentenced to pay a fine or go to prison. Emmeline offered to pay their fines, but the two refused and were imprisoned for several days. It proved the turning point in the suffrage campaign. As a result of extensive newspaper coverage, Deeds not Words got noticed.

In 1907 the WSPU moved its headquarters to London and Emmeline left her job as registrar of births and deaths, her only source of income. She now had no settled home and lived in various rented flats, hotels or homes of friends, but was awarded a stipend of £200 per annum from WSPU funds.

Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence became treasurer of the organisation in 1906. She and her husband, Frederick, were wealthy business-people and she brought those skills and some personal money to the Union. Donations from supporters were often generous, and at some meetings, where the charismatic Mrs Pankhurst spoke, as much as £14,000 could be raised. Money, jewels and other valuables were frequently thrown onto the platform.

Emmeline Pankhurst’s first experience of prison came early in 1908 when she led a deputation to the House of Commons and they were arrested for obstruction. She served a month in what was known as the second division, reserved for common criminal offenders, rather than the first division for political prisoners. Later that same year, in October, she was back in the dock in Bow Street, accused of incitement to disorder with Christabel and Flora Drummond – a WSPU organiser known as ‘The General’ because of the uniform she chose to wear. They had published a handbill encouraging a ‘rush’ on the House of Commons. The three women defended themselves in court. Emmeline’s speech in her defence and her description in the dock of the miserable lives led by so many women moved people to tears. Nevertheless, she was sentenced to three months in jail.

Prison b...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Dedication

- Contents

- Introduction

- Mary Wollstonecraft

- Elizabeth Garrett Anderson

- Millicent Garrett Fawcett

- Emmeline Pankhurst

- Constance Markievicz

- Nancy Astor

- … and Ethel Smyth

- Copyright