![]()

III.

SHINJO

![]()

9.

Attaining Mastery

Using Skillful Means to Bring Dharma to the Masses

A ceremony to officially consecrate the new temple was held on February 5, 1939, and was led by Shinpo Yoshida, an official from the Daigoji Monastery. The formal name of the new facility was the Tachikawa Fellowship of Achala of the Daigo School of Shingon Esoteric Buddhism. In practice, the facility is usually just referred to as “the hall.” By any name, the temple was founded as a branch of Daigoji and belonged to the Daigo school of Shingon esoteric Buddhism.

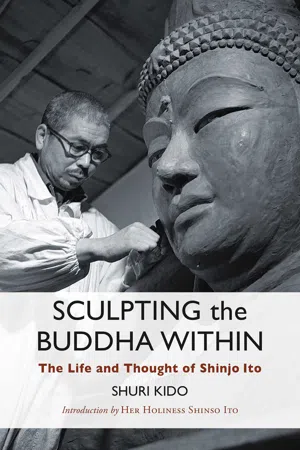

Commemorative photo taken on the day of the consecration ceremony of the Tachikawa Fellowship of Achala, with Shinjo sitting in the center of the front row

Shinjo put up a board outside the temple with the following message:

All who yearn to breathe free from anguish and distress, all who are buffeted by the winds and waves of the stormy voyage through life, come here!

The innermost truths of Shingon esoteric Buddhism are transmitted within this training hall; here we aim to facilitate attainment of peace of mind and a state of calm through the practice of its rituals and prayers.

Consultations

Authentic Spiritual Readings based on:

I Ching

Astrology

Physiognomy

Feng shui

Palmistry

We offer:

Protection from curses, mishaps, and ailments

Private consultation in all matters

Effective means of gaining complete peace of mind and spiritual calm

The board advertising Shinjo’s services certainly appealed directly to superstition and folk belief, touting as it did a variety of forms of divination, fortunetelling, and protection from curses. Discriminating denizens of Tokyo, even back then, would have scoffed at its grand promises. Shinjo was aware of how the message would be perceived by some, but he posted it anyway. A few years later he reflected in his diary on the reasons for doing so:

Orthodox religious groups such as those at Takahata or Mount Takao in this area would not put up a sign like this. They may attract many people, but services and ceremonies alone cannot heal a person’s soul.

This sign will surely be cause for ridicule among the “cultured,” the so-called intellectuals of society. The more popular my services become, the more what is written on the sign may be used against me. I anticipate this. Yet it does not deter me from posting the sign.

While those taking pride in their sophisticated ways may superficially scoff at us, I know that, in truth, they too need help. I believe religion is for responding to such needs. The day they get what they need — after having come in response to what is written on the sign — they may very well ask me to take it down.

This diary entry brims with Shinjo’s determination and reflects his view of religion. Sophisticated, rational, cultured people are likely to dismiss what he wrote as irrational superstition and may even laugh at it. But from Shinjo’s point of view, sophistication and rational thinking alone cannot resolve people’s suffering. In fact, the opposite is clearly true: suffering persists even for those steeped in culture and rationality. I believe the Buddha rightly said that everyone’s life is characterized by the four sufferings of birth, old age, sickness, and death.

For Shinjo, it was evident that although rationality and sophisticated culture may provide pleasant and enriching experiences in life, they do not deal with the reality of our births, the avoidance of aging, the inevitability of falling ill, or the certainty of our deaths. He wanted us to be aware that these are existential realities that we may not consciously realize, but deep in our hearts we are certainly aware of them. Sooner or later we will confront suffering and seek relief. When pain and suffering strike, seemingly without rhyme or reason, the rationality or irrationality of the means to relieve it is no longer of primary concern; we simply search for relief, sometimes in places we normally would not.

No matter how cultured we might be, Shinjo felt, as human beings we all suffer problems that we cannot solve on our own. Shinjo thought that religion was exactly what we need at such times. Even at this early stage of his teaching career, Shinjo sought to adapt his teachings and practice to modernity. For him, that meant not only protecting the tradition that had been passed down from master to disciple, but cultivating a living faith tradition rooted in the layperson’s struggle to live life and be human.

So with great determination, Shinjo hung his sign specifically to speak to those plunged into the depths of suffering. He didn’t discourage people from coming to the Fellowship of Achala to solve their problems. In fact, the prayer rites advertised on his sign had a reputation for being quite effective. He was beginning to be known as a priest with a great spiritual capacity, and the Achala enshrined in his temple was rumored to have miraculous powers. These are no doubt the primary reasons that the number of people attending his temple continued to grow.

However, despite his acceptance of the fact that people would turn to his fellowship hoping to solve their personal problems, Shinjo did not intend to become the type of religious leader who espoused that prayer or spiritual powers can solve all of one’s problems. The protection that prayer rites provide may help people with mundane problems, but Shinjo knew that getting too caught up in these sorts of workaday miracles and the mystery of spiritual powers would lead one astray from the true purpose of Buddhism, which is liberation from suffering altogether and the attainment of our own buddhahood.

A pithy “three-phrase teaching” summarizes the essential message of the Mahavairochana Sutra. When questioned regarding the foundation of all wisdom, Mahavairochana, the personification of cosmic truth itself, says, “Make an attitude of enlightenment the seed, make great compassion the root of your deeds, and complete these with expedient means.” In other words, wisdom begins with an aspiration to achieve enlightenment, and its foundation is compassion that seeks to guide all beings out of suffering. Based on wisdom and compassion, ultimately it is to be able to be selfless and see what expedient means are necessary to lead others to enlightenment. Shinjo’s appeal to the mundane concerns of ordinary people with his sign embodies this three-phrase teaching.

Keeping Miracles in Perspective

In response to an article on faith healing that appeared in a Shingon journal called Rokudai, in May 1940 Shinjo wrote in his diary:

I for one cannot agree with the idea of relying on the spiritual to treat only illnesses. We must remind ourselves of what is fundamental to the liberation that buddhas aim for: that we sentient beings have the potential and capacity to climb out of states in which we are dominated by inborn animal instincts. Doing so will help us come within the bounds of true humanity, and from there we can elevate ourselves further and further until we reach the state of enlightenment we find in buddhahood. It may be that mystical experiences of spiritual healing may occur in the process of our religious efforts to elevate ourselves, but any spiritual path that diverges from the primary goal — enlightenment — is, I would say, one that has gone astray.

I can’t say that the spiritual therapy introduced in Rokudai makes me happy. It sets forth only spiritual healing. [Likewise,] teachings that focus only on physical ailments or on what we can see with our eyes are empty of truth. The Dharma must not be turned into something that is false. I realized this point in reading this article.

For Shinjo, even if esoteric Buddhist rituals heal both spiritual and physical illnesses, that is never their ultimate aim. Healing may occur as we develop the enlightened attitude of bodhichitta (bodhi mind, the aspiration to awaken), but it is only a secondary effect. Incidental healing is not the essence of Shingon Buddhism, nor of any authentic religion for that matter. Shinjo warned that if we get too caught up in these phenomena, we lose sight of the essence of Buddhism.

Shinjo’s attitude concerning spiritual powers, whether his own or of others, calls to mind the famous Japanese Buddhist monk Myoe, who lived during the Kamakura period (1185–1333). Myoe was said to have possessed special abilities. He was famously responsible for making it rain after a drought of more than eighty days and became known for his prescience in other matters as well.

Once, in the middle of performing a ritual, Myoe said, “An insect has fallen into the hand-washing basin. Take it out immediately and release it.” When his disciple went to look, he found that a bee had fallen into the basin and was on the verge of death.

Another time, in the middle of meditation Myoe said, “A small bird is being attacked in the bamboo grove behind the temple. Go and see.” When the disciple went to check, he found a hawk grappling a sparrow, so he chased the hawk away. Such mysterious happenings are said to have occurred so often that Myoe’s disciples grew afraid that he could see everything they were doing, and were always careful about how they behaved. People began to consider Myoe a manifestation of the Buddha himself.

But Myoe would have none of it, as indicated in a biography of the monk titled Toganoo Myoe Shonin Denki:

Oh, the things these foolish people say! Instead they ought to take pleasure in meditation and practice the teachings of the Buddha. I never intended to become this way, but after practicing the Dharma for many years I naturally became accomplished without even realizing it. It is nothing to boast about. It is like drinking when you are thirsty or approaching the fire when you want to be warm.

Regarding his own powers, Shinjo clearly agreed with Myoe’s attitude. Buddhism teaches that sincere religious training can naturally produce a state of samadhi or profound concentration. Samadhi itself is nothing special; anyone with sufficient training can achieve it. According to Myoe and Shinjo, extraordinary abilities are as ordinary as the impulse to drink when thirsty or to go near a fire when cold. Those who attain samadhi can perform “miracles” related to what Buddhist sutras call the “six supernormal abilities” (abhijna):

1. the ability to travel freely anywhere one wishes

2. the ability to see anything anywhere or to foresee the future

3. the ability to hear any sound anywhere

4. the ability to know the minds of others

5. the ability to know past lives

6. the ability to eliminate the delusions at the root of suffering

Of course, these sound fantastical and are far beyond ordinary human capabilities. But such stories about miraculous powers are not unique to Buddhism. Christianity and most other religions preserve in their traditions stories of saints who exhibited similar powers.

Even though Shinjo and Tomoji had spiritual abilities, Shinjo consistently warned against becoming fixated on the supernatural aspects of religion. In fact, he advised his followers that if they were sick, they shouldn’t rely on faith alone but should see a doctor. Shinjo may have felt compelled to warn his students because of his own painful experience of losing Chibun. “Practice is not about wanting buddhas to comply with our human desires,” Shinjo wrote in his diary.

No religious practitioner is omnipotent. Even the Buddha himself couldn’t prevent the destruction of his own relatives. If an esoteric ritual healed a disease, it simply meant that the ritual had been perfectly c...