![]()

Pink and Blue in the Womb

YOUR PERIOD IS ONLY one day late, but you can’t wait any longer. You do the test, waking up to pee on a stick at 6 A.M. Then you wait, smiling nervously while your husband stares at the result window that’s shaking subtly in your hand. Finally, some faint lines begin to emerge. You flash back and forth between the tester and the instruction diagrams. . . . It’s looking good. Yes, it’s definitely looking like a positive. Your eyes meet. It’s going to happen! You’re going to have another baby!

“Oh, please, let it be a boy this time,” your husband blurts out; it’s still too early in the day for him to keep his deepest wish in check. You share his hope, your two daughters having satisfied all your frilly-dress dreams.

Home pregnancy tests are amazing, but they can’t yet tell the sex of a baby. That’s partly because the earlier it is in pregnancy, the less difference there is between the sexes. Boys and girls are identical for the first six weeks4 of development. While many expectant parents begin fantasizing about one or the other sex from the very beginning of pregnancy, the embryo itself appears conspicuously uncommitted.

Sexual differentiation begins about midway through the first trimester but isn’t obvious by ultrasound until the end of that trimester, at the absolute earliest. Fetuses take their time before presenting themselves as clearly male or female on the outside. Inside their brains, sexual differentiation is slower still.

Nonetheless, differences in the brain and mind do take root before birth. You can’t see it in an ultrasound scan or hear it in the fetal heartbeat, but boys’ and girls’ brains are influenced in the womb by their different genes and hormones. We know this from their different medical risks and especially from studies of children who for some reason were exposed to abnormal levels of sex hormones before birth. For eons, old wives have claimed that there are ways to tell the difference between male and female pregnancies, and there is some reason to think this may be possible, even if the methods are not yet rigorously proven.

In this chapter, we’ll explore the fascinating process of sexual development before birth. How do the sex chromosomes work? When are the sex hormones, including testosterone and estrogen, first produced? Are there any differences in the behavior or abilities of boy and girl fetuses? Is there any truth to the folklore about differences between male versus female pregnancies? And most important, what is the impact of these first nine months on the later differences between boys and girls?

The Moment of Chance

Development may be an intricate dance of nature and nurture, but here’s one instance when nature unambiguously sets the ball rolling.5 A baby’s sex is decided at the moment of conception, when one sperm, carrying either an X or a Y chromosome from dad, penetrates one egg, carrying one of mum’s two X chromosomes. If an X-carrying sperm wins the race, the merger produces an XX genotype, and the fertilized egg, or zygote, will grow into a girl. If it is a Y sperm that outswims its five hundred million competitors, the baby will be a boy.

You can’t see the difference between male and female zygotes, even under the highest-power microscope. Doctors performing in vitro fertilization (IVF) screen tens of thousands of fertilized eggs each year, but separating male from female is a complicated, somewhat risky procedure involving the removal and testing of one cell from an eight-cell embryo. Known as preimplantation genetic diagnosis (PGD), this procedure can be used to identify male embryos for mothers known to be carriers of sex-linked recessive genetic disorders, such as hemophilia, Duchenne’s muscular dystrophy, and fragile X syndrome (which produces mental retardation in affected boys). Such disorders have a 50 percent chance of afflicting a carrier mother’s son, who inherits his only copy of the X chromosome from one of his mother’s two X chromosomes.

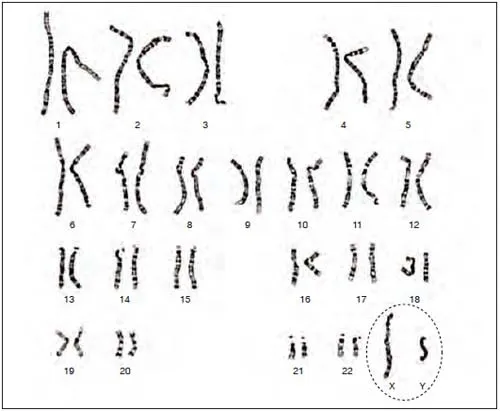

Figure 1.1. Male human chromosomes magnified about two thousand times, with the sex chromosomes circled. Of the forty-six total chromosomes, the only difference between the sexes is the presence of the small Y chromosome in boys. Girls have two copies of the X chromosome but no Y chromosome.

More recently, however, some doctors have extended the use of PGD for the purpose of “family balancing”—permitting parents who already have one or more children of one sex to select a fetus of the other sex. It’s an expensive procedure and controversial, since it involves the creation and disposal of unwanted embryos. Nonetheless, an increasing number of parents are using PGD to guarantee that their next baby will be the “right” sex.

For parents who don’t require in vitro fertilization, there is another scientifically based method to select their baby’s sex. Called MicroSort, it was developed in 1998 and, like PGD, is performed in just a few reproductive centers in the United States, for a hefty fee. In this case, the sorting takes place before fertilization and is based on a subtle difference between Y-carrying and X-carrying sperm. Because the Y chromosome is only about one-third the size of the X chromosome, male sperm are slightly smaller than female sperm: 2.8 percent smaller, to be exact. Scientists have exploited this difference by staining the sperm in a semen collection with a fluorescent dye and then running them down an extremely long tube that lines them up in single file. At the end of the tube is a fluorescence-sensitive cell sorter, which diverts the more brightly glowing X-carrying sperm to a separate collection from the dimmer Y-carrying sperm. Once separated, the sperm of choice are used for artificial insemination, which results in a successful pregnancy about 10 percent of the time.

The latest data indicate this method is quite reliable for producing female pregnancies: about 90 percent of pregnancies achieved after X sorting resulted in a female child. The success rate for boys is lower (75 percent), apparently because more X sperm get mixed in with the Y sperm than vice versa. Nonetheless, the use of MicroSort is steadily growing, with more parents every year willing to stump up the fee and undergo artificial insemination to bias the sex of their future offspring. Interestingly, thus far American parents have used MicroSort to select for girls more often than boys, either because the success rate is higher or because mothers are frequently the ones initiating the process.

Scientists may soon supplant both PGD and MicroSort with another technology for sex determination. It’s based on the recent discovery that small amounts of fetal DNA actually cross the placenta and enter a pregnant mother’s bloodstream. Using probes for specific DNA sequences located on the Y chromosome, researchers have shown that they can screen a woman’s blood as early as seven weeks into pregnancy and determine whether she is carrying a male fetus.6 Already, a slew of genetic entrepreneurs have hung out their Internet shingles promising “guaranteed” sex determination for just a few hundred dollars and a couple of drops of blood collected at home. Such testing is not subject to regulation by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, so there is no proof of claims of “as high as 99.9 percent accuracy.” One company, Acu-Gen of Lowell, Massachusetts, is even facing a class-action lawsuit brought by parents who were given the wrong results using Acu-Gen’s Baby Gender Mentor testing service—usually, parents were told they were having a boy when in fact the mother delivered a girl. But as long as they stay legal, such services will inevitably become widespread. The opportunity to find out a baby’s sex so early and in such a private, inexpensive, and noninvasive way is simply too alluring to avoid exploitation in this Wild West era of genetic testing.

Sex selection: high-tech, low-tech, and the ethics of choosing babies by gender

MicroSort and PGD are only the latest in a long history of methods parents have tried to bias the sex of their future children. Most have been pure folklore, no more scientific than relying on the direction of the wind (Aristotle’s theory) or on which side of the bed the husband hangs his pants (right for a boy, left for a girl, according to medieval legend). However, things turned more empirical in the 1960s and 1970s, when scientists began characterizing differences between X- and Y-containing sperm. One of these scientists was obstetrician Landrum Shettles, who detailed his theory in the paperback guide How to Choose the Sex of Your Baby. Republished as recently as 2006, this widely read book claims a success rate of 75 percent for girls and 80 percent for boys. Though originally advising a combination of measures (specific intercourse positions and precoital douches to favor male or female conceptions), Dr. Shettles eventually settled on the timing of intercourse as the key factor. Male sperm, he argued, are not only smaller but also faster and shorter lived, so intercourse closer to the moment of ovulation (egg release) is claimed to result in more male conceptions, while intercourse a few days before ovulation is said to produce more females. (Sperm can live up to six days inside a woman’s reproductive tract, but an egg lives less than a day following ovulation, so the overall window for fertilization spans from about six days before to one day after ovulation.)

The theory makes sense, except for the fact that male sperm are not the quicker, wilier critters Dr. Shettles imagined them to be. Research has exploded since the advent of in vitro fertilization, but other than MicroSort, no reliable way to separate X-carrying from Y-carrying sperm has been identified. Still, there are plenty of parents who swear by Shettles’s system, and it’s charming to imagine all the dog-eared copies of his book hastily tossed off the bed by parents passionately trying to conceive either a boy or girl. Of course, it’s easy to collect glowing testimonials when the chance of conceiving the desired gender is already 50 percent, but the theory was debunked by a large 1995 study that found that the timing of conception has no bearing on whether a boy or girl is conceived.

Parents do care passionately about the sex of their children, which raises all sorts of ethical issues as modern technology makes it increasingly possible to control this fate. Already, the ratio of boys to girls has become dramatically skewed in several Asian countries, where millions of parents have illegally aborted unwanted female fetuses after ultrasound sex determination. Several nations, including Canada and most of Europe, have responded by banning sex selection used for nonmedical reasons (that is, beyond detecting sex-linked disorders such as hemophilia). The U.S. government does not appear poised to do this, although the American Society for Reproductive Medicine, the organization that oversees such technologies, declared in 2001 “that initiating IVF and PGD solely to create gender variety in a family should at this time be discouraged.” But this policy is already being flouted by several high-profile IVF clinics that are unable to resist the multimillion-dollar revenue.

The situation is bound to get even worse with this newest wave of blood testing. According to data from the 2000 U.S. Census, parents who identified themselves as Chinese, Korean, or Indian showed an excess of second- and third-born boys. For parents’ whose first children had been girls, the ratio for second-born children was 117 boys for every 100 girls; if the parents’ first two children had been girls, the ratio was a striking 151 boys for every 100 girls. (For white Americans, the ratio was 105 boys to 100 girls, regardless of older siblings’ gender.) The inescapable conclusion is that these nationalities are selectively aborting female fetuses —on U.S. soil, and even before the advent of at-home sex-determining blood tests.

The debate about sex selection is certain to heat up as the technology comes within the reach of more and more parents. Thus far, fertility doctors have barely blinked each time ethicists have challenged their increasing liberties over human reproduction. The issue is more critical in Asia, where feminists realize that the greatest hope for squelching sex selection is not through its legal restriction but through improving the status and equality of women. Nonetheless, it seems clear that sex-selection technology is here to stay unless doctors themselves reject the idea that, as one fertility specialist puts it, “being a boy or girl is a medical handicap.”

How Boys Are Made

Of course, fertilization is just the first step in making a boy or a girl. What happens next depends on one tiny gene, which is located on the short arm of the tiny Y chromosome. As scientists only recently discovered, it doesn’t take the whole Y chromosome to make a boy, merely this one microscopic stretch of DNA, known as SRY, scientific shorthand for “sex-determining region of the Y chromosome.” SRY was discovered by British researchers studying a rare population: men with two X and no Y chromosomes. These XX males look, act, and consider themselves to be men, all because the single SRY gene jumped aboard one of the X chromosomes some time during sperm formation. SRY’s function has been confirmed based on the opposite, and equally rare, group of XY females: individuals who each have both an X and a Y chromosome but whose SRY gene has been deleted or mutated. In spite of their male genotype, children with this mutation look and feel like normal girls, at least until puberty, when their unformed ovaries prove incapable of supporting menstruation and breast development.

SRY is first activated about five weeks after conception within the genital ridge, the primordial, unisex gonad that has the potential to develop into either ovaries or testes. By six weeks, SRY has initiated its most important act: molding this generic gland into the male testes. SRY codes for a type of protein known as a transcription factor, which binds to the DNA in a cell’s nucleus and turns on or turns off genes that generate the structure of cells and tissues. Although the details of its actions are still being worked out, SRY is clearly the master switch in this sequence, flipping on the full cascade of male development in normal XY embryos.

Once SRY finishes its job, the testes take over the most critical work of male differentiation. They produce testosterone, of course, but first they secrete a factor known as anti-Mullerian hormone (AMH), which is essential for linking up the correct plumbing for male urogenital function. Testosterone and AMH are hormones, which means they are released by glands (in this case, the testes) and flow through the blood to affect many other tissues, including the urogenital system, muscles, bone, and, of course, the brain.

The gonads are not the only reproductive organ that passes through a brief unisex phase. Each of us begins life with two complete sets of would-be reproductive tracts connected to these undifferentiated gonads. One set is the Wolffian ducts, named after an eighteenth-century German anatomist, which can morph into the vas deferens, seminal vesicles, and other internal parts of the male reproductive tract. The other is the Mullerian ducts (named after another German scientist), which can become the oviducts (fallopian tubes) and uterus in females. In males, the testes begin secreting AMH just six weeks after conception. As its name describes, AMH causes degeneration of the Mullerian ducts, obliterating the baby’s potential female plumbing. By ten weeks after conception, the testes have begun producing significant quantities of testosterone, which transforms the Wolffian ducts into the various sperm- and semen-carrying tubes of the male reproductive tract. Females retain their Mullerian ducts (because they have no testes to secrete AMH) but lose their Wolffian set due to their lack of testosterone.

All of this sounds quick, and sexual differentiation does get an early start in the developing embryo. But finishing up the process takes several more months. In girls, the uterus and vagina aren’t fully formed until about twenty weeks past conception. Externally, boys and girls are indistinguishable until at least twelve weeks past conception. Both the penis and the clitoris evolve from a common structure, the genital tubercle, which grows larger under the influence of testosterone, smaller if testosterone is absent. Still, these structures can remain hard to distinguish under ultrasound, even at five months’ gestation. (That’s why ultrasound technicians typically issue a disclaimer at this stage about not being able to guarantee they can tell you the sex of the fetus.) Slowest of all steps in genital development is the descent of the testicles, which form within the body cavity but move outside to the scrotum during the latter half of gestation. About 4 percent of full-term baby boys are born with undescended testicles, but the number is much higher—up to 33 percent—for boys born prematurely. If the testicles fail to descend by twelve months of age, which happens in about one out of every hundred boys, a simple surgical procedure can correct the problem.

Like the Wolffian ducts’, the development of most male reproductive organs is critically controlled by testosterone. The testes secrete their first shots of testosterone just six weeks after conception. This hormone peaks in the male fetus between fourteen and sixteen weeks of development (sixteen to eighteen weeks of pregnancy) at a level some eight times higher than in females, and then it gradually declines until twenty-four weeks, when its level is merely twice that of females. Testosterone is responsible for expanding the penis out of the unisex genital tubercle, for fusing the urethral folds along the midline (which forms the shaft of the penis), and for creating the scrotal sac.

The importance of testosterone before birth is highlighted by individuals who can’t respond to it. A genetic male who has a normal Y chromosome but lacks the receptors for circulating testosterone looks like a normal female, because the hormone can’t exert all these critical actions. This condition is known as androgen insensitivity syndrome, or AIS, because the receptors that bind testosterone also bind other male hormones, which are called androgens. AIS is rare, occurring in about three of every one hundred thousand children, and it often remains undetected until puberty, when the child everyone had assumed was ...