![]()

CHAPTER ONE

The Economy of Work

SETH BERNARD

As its central theme, this chapter takes up the topic of ancient work’s relationship to economic performance and growth. Were workers in the Greco-Roman world more or less productive than workers in other times and places, and why? Over the long run, even minimal population growth in any society entails more workers, and thus greater aggregate production. However, most scholars now allow for a rise in per capita output, or intensive growth, for some parts of classical Greece and the Hellenistic East, and above all for the politically integrated Mediterranean under the Roman Empire. The level of development can only have been modest by the standards of modern economies, and a range of opinion continues to exist over the distribution of growth and its effects on real incomes and living standards.1 Still, if we think that the economies of parts of the Greco-Roman world expanded intensively to some degree, the corollary question arises: what features supported such growth?

Answering this depends upon an investigation of work. This is because of the obvious difference between premodern economic development and the continuous and progressive growth exhibited by modern economies starting from the time of the Industrial Revolution. Historians have put considerable energy into understanding why modern economies suddenly expanded at a different rate than in the past, with recent models stressing institutional changes, technological innovation, relative factor prices, or the chance discovery of fossil fuels. What is important is that most explanations start from the assumption that premodern economic expansion derived, by contrast, chiefly from the division of labor. Such growth was “Smithian,” called after Adam Smith’s observation that the extension of commercial markets through trade allows for finer divisions of labor, greater efficiency, and increased productivity. Notably, without concomitant changes to technology, capital stock, or institutions, Smithian growth will ultimately be constrained by the market’s extent, while gains through specialization reach a point of diminishing returns. In short, unlike modern growth, premodern growth was typically modest and temporary, and depended greatly upon the scope of trade and the division of labor.

This is not to say that all ancient growth everywhere was Smithian, and most historical “efflorescences,” to use Jack Goldstone’s phrase, have involved a mixture of different forms of economic growth.2 To be sure, technology raised productivity in parts of the ancient economy; we clearly see its effects in agricultural irrigation or in the application of water power to milling and mining.3 But the fuel of ancient production remained predominately human labor, and it is therefore revealing that the rise and fall of economic prosperity seems to have coincided with the expansion of trading zones following the integration of successive political entities. The archaeological evidence in support of an increase in the extent and volume of trade seems decisive. More amphorae, shipwrecks, and atmospheric metal pollution in the Greenland ice cap, likely related to coinage production, form some of the better-known proxies.4 However, since trade in and of itself speaks to the distribution of goods and not necessarily to a rise in their production, an understanding of how such evidence relates to economic development revolves, once more, around the question of whether trade brought about more efficient production, and this fundamentally ties a study of ancient economic performance to the dynamics of work.

The most influential attempt to distinguish the character of work in classical antiquity has been the Marxist association of Greco-Roman societies with the slave mode of production, and the idea that ancient production was particularly dependent upon slavery. Moses Finley and Keith Hopkins described Athens and Rome as not just slave-owning societies, but as “genuine slave societies.”5 Translating this into quantitative terms has proven difficult, but the essential point seems valid: slaves not only made up a significant proportion of the populations of some parts of the ancient world, but slaveholding formed the basis of those particular political economies, and it was through slavery that the dominant classes in classical Athens or Roman Italy attained the wealth and status to sustain their dominance. While the attempt to differentiate Greco-Roman production from production in other societies is useful, we must be cautious in pursuing this schematic in all of its facets. For Marx, different modes of production ultimately served to highlight the unusualness of capitalism, which he saw as characterized above all by the pursuit of the accumulation of capital alongside the related commodification of labor. Under this view, wage labor was absent or marginal in precapitalist economies. Marxist studies of Greece and Rome have thus tended to minimize the role of free labor and emphasize the pejorative attitudes of Greek and Roman elites towards all manual labor. Finley, for example, saw Cicero’s famous equation in the De officiis of wage earning with slavery (1.150–1) as emblematic. The problem is that, alongside Cicero’s opinion, we find other classical authors praising diligence and work in more positive ways. Not only this, but there is plenty of evidence for ancient paid labor, even in some decidedly noncapitalist contexts, and wage earning does not appear to have been marginal.6 It has, for example, been argued that Roman wage-earners possessed an aggregate portion of the Roman economy not dissimilar to that controlled by the elite, so that their complete sociopolitical disenfranchisement seems unlikely.7 Thus, it is unfair to say that slavery trivialized ancient wage-earners either ideologically or economically. Instead, the more complex interaction between free and unfree labor in precapitalist economies like Greece and Rome becomes a matter of acute interest.

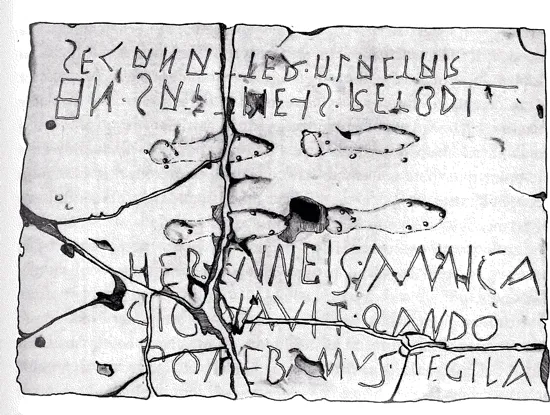

THE EVIDENCE

Ancient historians are accustomed to lament the scarcity of available economic data, although there remains useful information, as will be clear in what follows. It is also worth emphasizing the light archaeology continues to shed on the organization of ancient work. But there are also some frustrating silences. In particular, certain members of ancient households are difficult to trace. For example, Christian Laes argues reasonably that children contributed meaningfully to ancient production, although there is little direct evidence.8 The economic role of women is not only obscure, but poses problems in determining the extent to which ideologies associated with gender constrained reality. As early as Homer, we find a division of labor by gender, with men’s working sphere outdoors and women’s in the oikos or domus. This is an ideal, and we may think that economic stresses such as poverty or the harvest caused households to extend their labor, including their female members. Through Ulrike Roth’s work, we may suspect that slave women were more common in agriculture than is sometimes held.9 In urban settings, what evidence we have shows women largely confined to retail or service industries, or a limited number of crafts. As in agriculture, an aversion to women’s wage-labor may have been an easier ideological position for wealthier urban households, and there is some evidence to suggest that necessity pulled poorer women into the market.10 Moreover, as assertions about urban women’s work are based on funerary inscriptions naming occupation, we may be suspicious that epigraphic habits play a role in restricting women’s visibility. We catch a rare glimpse of women at work as semi-skilled or skilled building laborers at the Samnite sanctuary of Pietrabbondante in Italy, where a roof tile dated to around 100 BCE bears two sets of shoe prints along with a bilingual inscription made by two slaves responsible for the tile’s manufacture. The worker signing the tile in Latin was a slave named Amica; the status and identity of the individual signing in Oscan remains debated (Figure 1.1).11 All of this evidence aside, however, Richard Saller points out that gender attitudes may have had a real effect on family decisions to train women, cutting them off from certain skilled occupations deemed inappropriate to their gender, and to this point freeborn women are absent from the apprenticeship contracts found in Roman Egypt.12

FIGURE 1.1 Roof tile from Pietrabbondante with bilingual inscription in Oscan and Latin, c. 100 BCE. Based on La Regina, Studi Etrusci 44, 1976: 285. Reproduced with permission of Istituto Nazionale di Studi Etruschi ed Italici.

As this discussion implies, what little evidence exists for women’s work tends to document skilled labor. Unskilled women’s labor is practically invisible in the ancient economy, and this leaves many questions unanswerable. In particular regard to economic development, Sheilagh Ogilvie notes that it is precisely women’s position close to the boundary between household work and market work in early modern Europe that made them particularly sensitive to economic change, and growth could thus greatly increase women’s participation in the market.13 We are completely unable to trace how ancient families changed their allocation of labor in response to the positive incentives of growth. Women were employed, for example, in significant numbers as unskilled workers in building in early modern Britain.14 While building is held up as an important source of demand for unskilled labor in ancient cities, how this shaped women’s work, if it did at all, is impossible to tell.

TRADE AND THE INTERNATIONAL DIVISION OF LABOR

We start from a macroeconomic perspective with the role of trade in raising productivity by allowing for international divisions of labor. Alain Bresson notes that some archaic and classical poleis could have sustained their populations on locally produced grain, but only at great labor cost and by cultivating all available land.15 Instead, already by the archaic period many poleis began to import grain grown at higher productivity rates from areas beyond the Aegean including the Black Sea, Sicily, and Africa. Importing cheap food allowed for greater population density in those poleis at the center of the Aegean, while it also encouraged shifts in production and labor. To facilitate their engagement in foreign trade, many grain-importing Greek cities focused on exportable and more labor-intensive products, particularly wine. They frequently did so by expanding their use of slave labor, a shift already taking place by the archaic period in poleis like Chios.

Peter Temin uses similar principles of comparative advantage to interpret the Roman Empire, focusing on Italian wine and Egyptian grain.16 Because of the dependable fertility of the Nile flood, Egypt was associated with grain production for the imperial annona and the distribution of food to qualified citizens at Rome. The province was likewise known for viticulture, and some documents on papyrus even attest that new land in the Nile valley was given over to vineyards in the period immediately following Roman conquest.17 However, the issue is that of comparative not absolute advantage, and Temin’s suggestion that the empire was to some extent conceivable as divided along the lines of grain production and consumption is born out by Pliny’s Panegyricus, which praises Trajan not only for providing cheap grain to Rome, but for coordinating provincial producers and urban consumers throughout the Mediterranean (Pan. 29). Imperial interest lowered transportation costs—related to the annona, Pliny refers to the construction of roads and harbors—further allowing the development of trade. Inscriptions from cities in Asia Minor refer to the receipt of imperial Egyptian grain and confirm that areas beyond Rome benefited from such market coordination.18 This regional specialization allowed non-grain-producing regions not only to invest in slave-intensive agriculture, as with Italian viticulture, but also to carry higher urban populations, and thus greater shares of urban labor, than local food production may have otherwise allowed.

TRADE AND THE URBAN DIVISION OF LABOR

Thus, the international (or interregional) division of work closely relates to another division, that between urban and rural labor. The share of urban workers in antiquity has important implications for economic performance since urban workers do not grow their own food, but must obtain their livelihood through trade, with implied transaction and transportation costs. To feed a large urban population, an economy must produce a sufficient surplus by somehow raising agricultural production. With that said, the categories of urban and rural labor in Greco-Roman antiquity show considerable overlap. The predictable seasonal rhythms of agriculture allowed farms to contribute labor when available to the economies of nearby towns, while urban workers were sometimes employed on suburban estates during periods of high demand, such as the harvest. Such structural and reciprocal flows of labor between town and countryside were hardly unique to antiquity, but are still important.19 Classical Athens and similarly structured poleis were emblematic of the overlapping location of labor. The political integration of polis and chora implied a regular exchange of labor between town and countryside and a comparatively high share of farmers living in towns. Moreover, important Athenian industries such as the Laureion silver mines or the Pentelikon marble quarries were located in the chora. Nor is this the only place where we find major productive activities outside urban centers: the Tiber Valley’s massive brick industry is another well-known example.

Nonurban industry reinforces the fact that the contrast between urban and rural was not necessarily that between nucleated and dispersed labor since significant nonurban focal points existed in the structure of production in Rome’s imperial economy. In a ration document from the Mons Claudianus quarries, 917 workers are listed. On the imperial estate of Villa Magna in Latium, a barracks-like structure, perhaps an ergastulum, was built in the early third century CE to house some 200 to 240 individuals, plausibly much of the estate’s labor force along with their families, since several infant burials were found within the structure.20 These concentrations of labor were well beyond the suburbs of any major settlement.

Despite some interpretive problems, however, there are reasons to think that the Hellenistic period and particularly the Roman Empire saw a rise in urbanization rates. One indication is the proliferation of monumental urban architecture during these periods. Endowing cities with large-scale infrastructure was costly and implies a concentration of workers in urban centers. A second indication comes in the growth of several megacities, for lack of a better term. A select class of ancient cities including, at different times, Antioch, Carthage, and Alexandria contained several hundreds of thousands of people. Imperial Rome itself numbered perhaps a million residents. These very large cities represent a phenomenon that was not only unprecedented, but which was not repeated in western history until the growth of early modern European capitals such as London and Paris. The emergence of such ancient cities is inconceivable without a sign...