![]()

CHAPTER ONE

The Economy of Work

JAMES DAVIS

The economy of medieval work was about the choices that people made, or had imposed upon them, in earning a living or maintaining a household. At their core, these choices affected their material circumstances and standard of living; for some this was about survival, for others about the accumulation of greater wealth. This chapter will explore the paid and unpaid work that was available to medieval men and women, as well as the time they devoted to work. Without such a foundation, the cultural factors that permeated the organization, perception, and ethics of work cannot be fully understood. The range of experience across Europe and across six hundred years was undoubtedly broad, so the following discussion can only highlight some apparent commonalities without attesting to their applicability in all instances of time and space. Nevertheless, it is clear that labor was the prime productive force in medieval society and this made people into valuable assets for those with work to offer. In medieval Europe, the vast majority worked in the fields, or in gathering other forms of natural resources, and their main unit of production was the small, nuclear household. Yet much of our evidence about medieval work derives from substantial ecclesiastical or seigneurial households, or else from the ruling organizations of the town. Understanding the experience of the ordinary rural worker, male or female, often has to be ascertained through the prism of their employers. To add to this sense of opaqueness, precise figures about wages, prices, and earnings are not easy to come by, with accounts recording wages in an incomplete or localized manner that prevents disaggregation for individuals or time worked.

This chapter focuses on the choices of work that were available, recognizing the environmental, economic, and sociopolitical constraints faced by medieval people in their attempt to make a living. Throughout this period, labor remained the prime means to improve productivity, with technological advances and mechanical aids relatively limited. This meant that an active market in labor developed as the economy grew, but its form shifted in response to factors of demography and crisis. During the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, when the population was growing and wages were low in comparison to prices, employers were prepared to intensify their use of labor in order to boost productivity, through more manuring, weeding, and cropping. After the Black Death, as labor became scarce and wages increased, producers looked for ways to use less labor. They turned more to pastoral husbandry or else leased out parts of demesnes, whereby the proportion of family labor in the economy increased. Thus sheep production grew in England and Spain, while viticulture expanded in Burgundy and along the Moselle.1 The cost of labor therefore reflected the availability of labor and its demand, both of which could vary chronologically and geographically.

THE CHOICE OF WORK

The choices of medieval tenants and laborers “were not made freely, because they worked within the limits imposed by their social circumstances and technical knowledge, and by the soil, terrain and climate.”2 Across Europe around 1000, some 90 percent of people lived off the produce of land or sea and, wherever we look, there were forms of arable and pastoral agriculture, viticulture, or horticulture. The resources provided by the surrounding natural landscape certainly shaped opportunities for work. Those who lived near woods, forest, fens, rivers, marshland, or the coast may have had an alternative or a way to supplement their income through exploiting the particulars of their environment. This was especially important when the soil was not conducive to more traditional forms of agriculture. For instance, the Breckland of East Anglia (England) lacked the soils for farming but encouraged a multiplicity of working options, from collecting fuel and building materials to catching wildfowl and riverine animals.3 More upland areas or poorer soils were often used for pasturing sheep or goats, from Castile to northern England. This required less intensive work than cultivating arable regions or the vineyards of the Mediterranean.

The work that was available was also shaped by the type of settlement, whether hamlets, villages, small towns, or cities. As medieval people increasingly gathered in nucleated villages by the tenth and eleventh centuries, integrated and shared working of the land provided more economic efficiency and a balancing of risk. However, it also reinforced the authority of the lords who could more easily raise rents and services upon tenant holdings. The urban population perhaps doubled during the medieval period, providing more nonagricultural work, but it was still less than a fifth of the total workforce—though northern Italy and Flanders contained a substantial share. Nevertheless, the process of urbanization had a broader effect on the types of work and organization of production, not only in the towns themselves but on the surrounding manors and estates. Production for urban markets increased; credit and capital flows developed; and wage differentials stimulated labor migration.

We should not assume that every man in the villages worked in the fields. There were many men who were employed as specialized carpenters, smiths, tailors, bakers, and brewers. Many males may also have engaged in more than one activity, with carpenters and smiths also holding land which they worked part-time. All medieval economies had nonagricultural occupations and a certain level of trade. The extent varied across time and regions, but even outside towns significant pockets of rural industry developed such as pottery, mining, cloth making, and charcoal burning. In the Carolingian period, textile production was a normal by-occupation for peasant wives, while in various parts of eighth- and ninth-century Europe there were workplaces called gynaecea where servile women had to undertake obligatory handicraft services.4 The wide range of occupations and industries available in rural areas by the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries was evident in the tax returns for England, such as the forty different crafts listed in the Wiltshire subsidy of 1332.5 Some regions had a concentration of particular industries, whether the tin mines of Cornwall and Devon, the lead mines of Derbyshire, Durham, and Northumberland, the metal working of south Germany, or the cloth industries of Flanders and Arras. The development and expansion of such industries stimulated new income streams for workers, as well as boosting local agricultural production and services. Similarly, the growth of towns and market networks across Europe, particularly in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, provided new opportunities. In response to heightened consumer demand, there were more areas of specialized agriculture that concentrated on cash crops and, in turn, attracted groups of workers. “Fields of crocuses in parts of Tuscany yielded precious saffron. Picardy in northeast France became prosperous from vast fields of woad, planted for blue dyestuff. Plantations of mulberry trees in parts of Greece and Italy supplied the only leaves that silkworms would eat.”6

Within all these communities, a socioeconomic hierarchy determined who worked for whom. The main employers of a concentration of workers were the big ecclesiastical institutions and wealthy secular lords. Lords controlled much of the land of Europe; while some was leased out to tenants on a range of terms, many would maintain and directly manage a piece of land (demesne) at the core of their rural manors as long as it benefited their coffers. This required workers, whether full-time servants, wage labor, servile labor, or slaves. However, throughout this period, the majority of employment was most likely provided by small-scale holdings and enterprises. Some rural families (free or unfree) may have had thirty acres of land or more, perhaps even akin to the lesser gentry, and were able to produce a significant marketable surplus. Such substantial holdings could not usually be worked by the family alone and thus they would hire a modest amount of wage labor and servants. Next down the scale were smallholders who were only able to produce a very small surplus and relied heavily on family labor. They had only a few acres of land and needed a supplementary trade or wage labor to make a living. Similarly, the landless had to survive primarily through wage labor, but very few enjoyed regular employment. They faced choices of mostly casual and seasonal work, often for their neighbors as much as for a lord.

SEASONAL WORK

Most agricultural work was seasonal and the agrarian rhythm moved from plowing to weeding, mowing, reaping, and threshing. Calendar illustrations reflected these seasonal activities, such as in the early Carolingian Chronicle of the Months from the abbey of St. Peter in Salzburg (c. 818). They are also exemplified in the following late medieval lyrics:

Januar | By thys fyre I warme my handys; |

Februar | And with my spade I delfe my landys. |

Marche | Here I sette my thynge to sprynge; |

Aprile | And here I here the fowlis synge. |

Maij | I am light as byrde in bowe; |

Junij | And I wede my corne wel I-now |

Julij | With my sythe my mede I mawe; |

Auguste | And here I shere my corne full lowe. |

September | With my flayll I erne my brede; |

October | And here I saw my whete so rede. |

November | At Martynesmasse I kylle my swyne; |

December | And at Cristemasse I drynke redde wyne.7 |

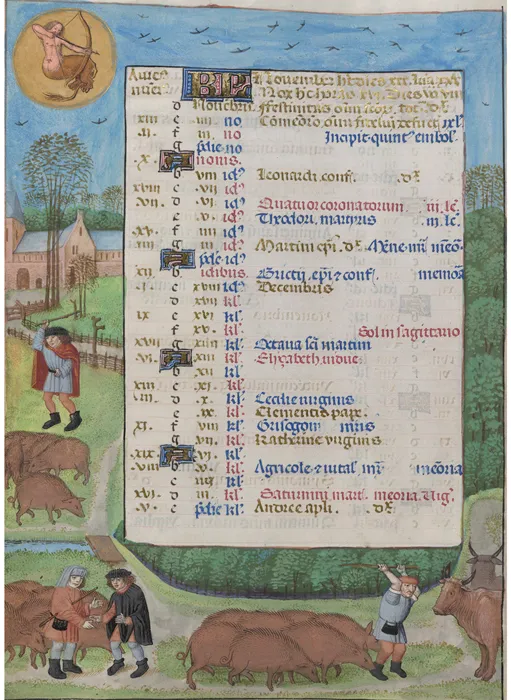

January was the month to keep warm, before the hard work from February to May for plowing, planting, and tending to crops. Plowing was tough and it is likely that all the family would be drawn into guiding the plow and directing the oxen. The fields then had to be turned and prepared with manure, while weeding was ongoing. In June and July, the hay was cut and stored, to be followed by the harvest of various grains. In October, pigs were fattened and fields prepared for winter wheat (Figure 1.1). November was for butchering and salting or smoking meat. Other tasks, such as collecting wood, digging drainage, taking care of animals, and general maintenance, continued throughout the year.8

FIGURE 1.1 Calendar for October, Breviary of Queen Isabella of Castile, c. 1497. British Library, Add. MS 18851, folio 6v.

The seasons thus determined the work of the household but also the fluctuating demand for waged labor. The above description highlights a northern European arable cycle, but such calendars had their origins in the Mediterranean regions with their greater emphasis on the cycles of the grape harvest between February and April. Similar regional differences in the seasonality of work were seen in areas dominated by pasture. Transhumance was a characteristic of these areas as both people and animals moved with the seasons in search of food. The fishing industry was also exemplified by seasonal migration of stocks, requiring an intensive expedition over a few weeks to bring in the catch and share the profits.

The daily work pattern was also shaped by the seasons. The changing hours of daylight naturally varied the length of the working day, with most working from sunrise to sunset. Consequently, it was customary in some regions for a winter day’s work to be paid less than for a summer day. Some artisans may have worked by candlelight, but this was frowned upon as both contributing to poor quality and an intention to escape prying oversight. The working day in towns had long been governed by the ringing of the bell that announced the daily rhythm of canonical hours (prime, terce, sext, and none), which determined when the town gates opened and when goods could be sold in the market. But this meant irregular hours depending on the season. French ordinances from the fourteenth century sought to define more clearly when the work day began and ended, as well as when meals could be taken, with the day’s divisions marked by bells. An ordinance of the provost of Paris from May 12, 1395 stated: “the working day is fixed from the hour of sunrise until the hour of sunset, with meals to be taken at reasonable times.”9

Laborers therefore worked long hours, but how efficiently and speedily they worked is difficult to determine. Did the imprecise measurement of time mean that workers were “task-oriented” rather than “time-oriented”?10 Most did not work on Sundays and by the late twelfth century the church was adamant that the Sabbath was a day for church and not for work—a sentiment that they sought to reinforce in church courts. Only victuallers appear to have been allowed to supply foodstuffs on every day of the week. Poor weather might also drive people home, particularly on frozen days in northern Europe, as well as the main feast days (and vigils) and fairs, which were not timed to accord with agricultural needs. This appears to have been the case for most workers and perhaps 115 days a year were potential nonwork days, though essential agricultural tasks would have continued.11

There is some evidence that village communities sought to regulate holidays and the activities of harvest workers, even before the labor legislation of the mid-fourteenth century. Similarly, in towns, craft guilds had long governed matters of working hours and rates of pay in the interests of employers not workers; journeymen were not generally allowed to bargain for their conditions of work. Clocks appear all over Europe from the mid-fourteenth century and become prominent in towns by the middle of the next century. This further regularized the divisions of the working day, particularly for those employed by others.12

THE WORKING HOUSEHOLD

The medieval household was the basic economic unit for consumption and production in both town and countryside. Consequently, all members of a household needed to ensure that the household ran effectively and prospered, or else they might be placing their very survival at risk during times of economic uncertainty and vulnerability to harvest failures. Most households were primarily concerned with their consumption needs, produced on a small scale and were heavily reliant on family labor; they had to work within their initial resource base and also the limits of their socioeconomic status. A family in the middle of their life cycle were likely to be at the peak of their production capability compared to those newly married or those reaching old age. The home itself and the surrounding land were often where work was undertaken, surplus produced, income generated, and resources maintained and consumed. It is clear that family labor was predominant in agricultural work, with those working their own holdings effectively self-employed, and thus every able family member had to contribute. This was particularly important for smallholders (perhaps five to ten acres), whose holdings were not sufficient to feed the family and provide a surplus. Finding a balance between resources, labor, and need could be problematic—ultimately the family had to be fed and sheltered—and aspirations to improve their economic and social status or provide for their children were secondary for the majority of those families who simply needed to make a daily living.

It would have been rare for a household to be completely self-sufficient, even where land was the core of their family economy. People frequently supplemented their earnings through irregular agricultural tasks or craftwork. It was often the case that the seasonal nature of agricul...