eBook - ePub

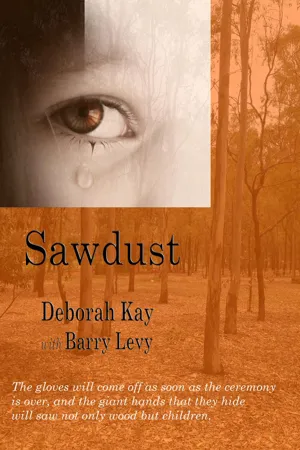

Sawdust

About this book

Winner, IP Rolling Picks 2013, Best Creative Non-Fiction.Deborah Kay teams up with award-winning social issues journalist Barry Levy to provide a courageous andcompassionate accountof what happened to her, and how she avoided being warped by her experiences, allowing, as she puts it, pockets of sunlight to shine through her.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1.

We were the ones in the dilapidated house everyone wondered about, the family on the Bruce Highway, just outside Gladstone. The ones who the passing world, adults and children, wondered what those people did for a livelihood, if they had money, how they could bear living there. While all these people raced by on their way to enjoy school holidays, to clinch deals on business trips, or whizzed by on their way back home from relatives and friends, they probably imagined a scruffy, scraggy family, Mum, Dad, kids, definitely too many kids, struggling to make ends meet. I often wondered, the dirt blowing into my windswept, tiny girl’s eyes, what it was they thought, those cars whooshing by our dusty property.

On the best of days, sometimes even the worst, as a child I thought Dad was a good bloke. At six foot and three inches he towered over everyone, and with his square-jawed Ricky Nelson looks and remnant Elvis Presley hairstyle, the larrikin in his sparkly hazel eyes would tell us stories about his youth, how he used to run amuck and get up to all kinds of mischief.

But also he would tell us how in the end he always did the right thing, how he helped out on his own mother and stepfather’s property that was in the Anondale district, near Lake Perenjora, not that far from where we lived.

Without boasting, he would tell us children how he was the young lad who carried the Olympic flame as it was heralded through the district for the 1956 Olympic Games in Melbourne. He is even mentioned in a book for it and had a large medal the size of my palm back then, in acknowledgement of the feat. I still have that book and my little brother Sam is the proud owner of Dad’s medal these days.

But the thing is, through his stories, through his gregarious and charming ways, he made us feel connected, and with him, or by ourselves, we would pick watermelons off the vine on hot summer days, especially at Christmas time, and the pink juice would pour from our mouths and drizzle through our fingers back to the thirsty soil from which the fruit sipped its nourishment.

On the surface of it, it could be easily gleaned from the highway, we may have been scruffy and scraggy, even scrawny and wanting, but we were children in love with life. On the best of days, sometimes even the worst, I loved Dad. I couldn’t help it. He had that sort of “connectedness” about him.

Always phenomenally dark-skinned from his work outside, a tan that continued even through the cold months, on crisp winter mornings he would look out from the back door and seeing the property covered in a layer of white flakiness that looked like someone’s sugar-frosted flakes had spilled over the earth, he would tell us Jack Frost had been around and left his tidings.

For us it was a huge mystery, and Jack Frost, although he never gave us anything but a scene of vast ice cold, was no less a figure in our imaginations than Father Christmas.

On those icy winter days, in the early morning cold, all of us kids would sit on the backstairs eating hot white toast covered in thick yellow honey. As the orange sun slowly rose on our expectant faces and over our bodies, the warm honey would slide down our hands and shine golden through our fingers. The image of frosty mornings with warm toast and melting honey shining through little fingers is one that will never leave me.

Inside the house, Mum, forever busy, would always be preparing something, usually meals, but also at times there was the sweet smell of things being baked in the oven. Usually it was biscuits made from no more than flour and sugar, but always hungry, we knew that smell meant there was a treat in store.

Her special treat for us on the odd occasion was a dessert called Roly Poly, which naturally we whooped and carried on about as though it was the best thing since Tim Tams, but in actual fact, personally, I didn’t really like Roly Polies. I think it was because of the mixed dried fruit she flavoured it with – it was hard on a kid lacking a sweet tooth. But then again I did look forward to the delicious warm custard that was inevitably served with it. Tim Tams we never had.

Mum had seductive curls of dark brown-red hair and I am told that’s where I received my own thick helmet of bushy, rust-brown hair that made my head look like a dramatically curly version of an echidna. In later years Mum would dye her hair black, giving her an Italian look that was apparently very appealing to men.

But she stood a mere five-foot tall and was, so to speak, half Dad’s size. She was also never “half” the match for him, either verbally or physically. She worked tirelessly in the kitchen and outside too. All day long, as Dad cut the timber, she would be the one snigging the cut logs with a tractor.

How hard could life have been for them? It’s hard to imagine even from my modest home in suburban Ipswich. Everything seemed dry and stoic in those days, everything a tough physical chore. Everything taking a mental toll. While the Beatles may have been starting out on rock and roll’s most lucrative career, and most people were beginning to really relish the post-war comforts that flooded into Australia’s cities through the fifties and sixties, we may as well have been struggling to survive on Mars.

The first two houses I remember were never our own, the one rented on the right side of the highway as we faced Gladstone, our biggest nearby city, and the other, which we moved into before I was three, on the left-hand side of the highway. Yes, between 1962 and 1965 we moved from one side of the highway to the other, and either way, the terrain was always hot and flat and dusty and people looked into our lives and made aspersions about us from their safe glass windows as they whipped by on the highway.

Dad always told us kids in those days life would have been different if his own father had not been killed in Singapore. In the War. It happened before Dad even had a chance to recognise the word Dad. With gargantuan courage and tears streaming in his eyes, he one day gathered us kids around his knees and told us his story: how his father was shot and killed defending the Commonwealth.

He even showed us a picture in an old magazine of Australian World War Two soldiers boarding a boat for Singapore. He pointed with a badly rasped working man’s finger at a tiny blurred head with a slouch hat and duffle bag whose face we could not see, and told us that was his dad.

He was very proud to have in his possession his dad’s War medals and carefully unfolded and then refolded the frail, yellowed telegram that his mother had received telling her that her husband, Bennett Gallagher, had died a hero, killed in action.

Also with tears in his eyes, he would tell us kids of his pet kangaroo and its cruel, eventual end, with its guts spilling out. He would sometimes drive us out to his first house, which was a shed with a corrugated tin roof that had no more than hessian bags for walls. It had a dirt floor. If we thought we had it bad, he had it worse.

Dad’s stepfather, Uncle Harvey, just happened to be their mother, Grandma Glad’s first cousin. There was a whiff of scandal associated with the union, especially in that there never seemed any proof of an official marriage certificate. But to us kids it didn’t really make much difference and we were happy to call Grandma’s “husband”, Grandad Harvey.

In Dad’s time, because his sister Dulcie did not get on with her stepdad – actually hated him – and because the small old farmhouse was now overflowing with two younger stepbrothers and four stepsisters, he and Dulcie managed to make a break from the cramped home, and moved in with Dad’s grandmother, our Great Grandma Cecily Flanagan and her son who was always known to us merely as Uncle Col. A bit complicated? That’s how it was in those days.

Dad, the hardworking timber-cutter, would talk to me more than to any of the other kids, or so it seemed to me. He would talk with me openly and matter-of-factly especially while he constantly sharpened his knives and saws in the old work shed.

When he was out working in the field, no one but no one, not even me, was allowed to come near him. We were only allowed to approach him when he got back to the shed of an evening. I always felt at those times like I was being loved. There was a part of me that trusted him, not just in any ordinary way, but deeply, in the skin.

A true working man and protector, he always warned us about people and how others may harm us, and there was always a profound sense with Dad around that we were safe. He was also very strict, as was Mum, and they almost never allowed us to visit other children or to have other children over.

The only children allowed over, and only at times, belonged to our nearest neighbours, the Groves, who had a couple of kids around me and my older brother Jim’s age. Because of the size of the open, dustbowl properties, near wasn’t exactly over the fence but was near enough to sometimes even hear the neighbours.

On the negative side, there was a feeling of isolation on the property, on all the properties we lived on, the one on the right side of the Bruce Highway as well as the one on the left – not to forget the property at the centre of my life, the large acreage Dad would eventually buy from the Crannies.

The Crannies were an older couple who thought the world of Dad. He would assist them in every way he could, always helping to cut things as well as hammer and move and fix things, and they treated him like a son. Eventually, at a rock-bottom price, they sold Dad 300 acres of their property on Perenjora Dam Road.

It was this property that we kids really grew up on. It had a border right on the rail line and the noise of tooting and shunting trains became the noise of my childhood. Not only did we have passing trains now, but we were still within a hop of the Bruce Highway. Wherever you looked, there were eyes that could see into our place. Not just from the cars now but from the trains as well.

Just like Dad was to the Crannies, he stood up for everyone who needed help. Always willing to lend a hand, he especially stood up for children.

Nevertheless, there was at times something in...

Table of contents

- CoverImage

- AuthorBio

- Acknowledgements

- Prelude

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

- 32

- 33

- 34

- 35

- 36

- 37

- 38

- 39

- 40

- 41

- 42

- 43

- 44

- 45

- 46

- 47

- 48

- 49

- 50

- Postscript

- Resources

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Sawdust by Deborah Kaye,Barry Levy in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & Developmental Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.