![]()

CHAPTER ONE: In the Beginning Was the Word: Christ in the Early Centuries

For in [Christ] the whole fullness of deity dwells bodily.

COLOSSIANS 2:9

AUGUSTINE , ON CHRISTIAN DOCTRINE

For many deceivers have gone out into the world, those who do

not confess the coming of Jesus Christ in the flesh. Such a one is

the deceiver and the antichrist

2 JOHN 7

In what way did he come but this, "The Word was made flesh

and dwelt among us,"

AUGUSTINE, ON CHRITIAN DO CTRINE

E ven before we get out of the pages of the New Testament, Christ comes under fire. During his earthly life and public ministry, the crowds, the religious leaders, even at times his own chosen disciples got him wrong. His life of working miracles and his teaching of who he was and what he came to do were in plain view for everyone to see and hear. Despite this, he was misinterpreted, denied, and rejected. In the face of his healing, he was called the son of Satan (Matt. 12:22-32). In the face of his teaching, he was called the mere son of a carpenter (John 6:4151). In the face of his death on the cross, he was mocked as the king of the Jews (John 19:19-22). And in the face of his resurrection, he was mistaken as a gardener (John 20:15). Fifty days after his death and after he had ascended back to heaven, Peter had to tell the crowd that Jesus, the very one whom they had seen and who had walked among them, was indeed the Christ, the Messiah, and that he was indeed the Lord (Acts 2:36). Those great crowds missed it, and, at least for a time, so had his closest followers. They had gotten him altogether wrong.

After his ascension and in the first decades of the church, the situation grew worse. The apostles and the early church contended with those teaching falsely about Christ. According to John, these false teachings centered around two poles. The first concerned the denial of Christ as the Messiah (1 John 2:22).The second concerned the denial of the incarnation, the teaching that Jesus was fully human and had truly come in the flesh (1 John 4:2; 2 John 7). These two poles of thought dominated not only the first century but the immediate following centuries.This chapter explores these false teachings and the response to them in the early church.

CHRISTOS AND COBBLERS

Mr. Christ. At least that’s the answer from the child in the Sunday school class to the teacher’s question concerning the one born in a stable in Bethlehem. In the child’s scheme of things, Jesus was the first name, Christ was the last. And, as his parents had taught him, he added the Mr. out of respect.

Of course, in the case of Jesus, Christ is not the last name, it’s a title. However, many, even those who should have known better, missed this. To them he was Jesus of Nazareth, or Jesus, the son of Joseph, the ancient versions of last names.1Acknowledging Jesus as the Christ, however, requires a great deal. The Greek word Christos means “anointed one” and is the counterpart to the Hebrew term meaning “Messiah.” Designating Jesus as the Christ requires that one see him as the long-awaited Messiah, the anointed one of God, who would be the redeemer and deliverer of the covenant people. That Jesus assumed the title Christ in both word and deed is undeniable. That those in his day and in the centuries following his birth denied him as the Christ is undeniable too.

The denial of Jesus as the Christ began among the leaders of the Jewish community. Jesus of Nazareth disappointed them as a candidate for the Messiah. He lacked charisma and gravitas, not to mention an army. The Israelite nation was faced with occupation by the Roman Empire, and Jesus failed to fulfill their dreams of a conquering Messiah. The Jewish leaders’ rejection of his claim to be their Messiah may be clearly seen in the exchange with Pontius Pilate. When that official ordered an inscription on the cross that would signify Christ’s crime as claiming to be “Jesus of Nazareth, the King of the Jews,” the Jewish leaders demanded that it be changed to read that he claimed to be the king of the Jews. Jesus claimed it, but they certainly did not want him. Pilate refused to change it (John 19:19-22).

One group in particular that was influenced by Jewish teachings denying the deity of Christ was the Ebionites. We don’t know much about this group. Epiphanius, the fourthcentury bishop of Salamis and later Cyprus, claims that Ebion founded this group. This may be a creative fiction. Other church fathers offered their own explanation of the name. The term likely comes from the Hebrew word for “poor.” They were the “poor” disciples. Later opponents of them would use the name sarcastically to refer to their less than stellar mental capabilities, calling them “poor” thinkers. We also speculate that this group probably arose in the first century, likely coming into prominence after the destruction of Jerusalem in A.D. 70. The Ebionites were scattered from Jerusalem and Israel and congregated initially in Kochaba but soon spread throughout the empire. Scholars further tend to see this group as an extension of the Judaizers, the faction that Paul contended with in his Epistle to the Galatians. They were in effect trying to be Jewish Christians, not quite ready to accept the teachings of Paul or the book of Hebrews or John. All of which is to say that they were falling short of what constitutes true Christianity. It appears that the Ebionites were unable to sustain themselves in walking this tightrope between Judaism and Christianity. By the middle of the 400s they had virtually become extinct, some migrating to Judaism, others affirming orthodox Christianity.2

HERESY

The English word heresy is a transliteration of both the Greek and Latin word. The Wycliffe Bible may contain the first occurrence of the English word, merely transliterating it from the Latin Vulgate at Acts 24:14. It occurs several times in the New Testament, initially meaning “sect” or “school of thought.” The Sadducees and Pharisees are termed a sect in Acts 5:17 and 15:5. The term is also used to speak of the Christians themselves in Acts 24:14 and 28:22. In the epistles the term is used to refer to groups that are causing division in the church, such as the ESV translation of the word as “factions” in 1 Corinthians 11:19. By the later epistles, especially 2 Peter, the term comes to mean divisive groups within the church that are promoting false teaching.In 2 Peter 2:1 the ESV translates the term as “heresies,” which are destructive and are brought into the church by false teachers. This particular heresy in 2 Peter centers on Christ. In the early church, teachings that went against Scripture were considered heresy, usually at synods. Once Christianity became legalized in the Roman Empire, a charge of heresy not only meant excommunication from the church but could also bring legal ramifications. As the church formulated and finalized the creeds, especially the Nicene and Chalcedonian Creeds, there became rather fixed and firm boundaries between heresy and orthodoxy. Augustine once said, in a rather lengthy letter dealing with heresy, that heretics “prefer their own contentions to the testimonies of Holy writ” and that they consequently separate themselves from the true, universal church.

Most of what we know about the Ebionites comes from the writings of the church fathers against them. Irenaeus mounted the first sustained refutation of them. He, in fact, was the first to use the name “Ebionites” in print, around 190. Hippolytus and Origen would later contribute their own refutations. The Ebionites viewed Christ as a prophet, and some of them even accepted the virgin birth. But they all denied his preexistence and consequently denied his deity. Eusebius, the first church historian, writing in 325, put the Ebionite heresy succinctly: “The adherents of what is known as the Ebionite heresy assert that Christ was the son of Joseph and Mary, and regard him as no more than a man.” While viewing Jesus as a mere man, the Ebionites nevertheless exalted Jesus as one who kept the law perfectly, and as a group they stressed the keeping of the law in order to attain salvation. Like the Judaizers of Paul’s day, they insisted on circumcision. Their faulty view of Christ led to a faulty view of Christ’s work on the cross. Their misunderstanding of the incarnation led to a misunderstanding of the atonement. They did not grasp the fact that Christ is the God-man who is for us. This fact makes all the difference for our salvation.3

Another and more sophisticated view that denied Christ’s deity circulated in the early church. This view, called adoptionism, held that God adopted the human Jesus as his son after he was born, either at Jesus’ baptism or at his resurrection. When the one God descended on the human Jesus, Jesus became the son of God and became the Christ, filled with divine power. Eusebius refers to this as “Artemon’s heresy.” We, however, know nothing of Artemon beyond this brief reference. Later proponents of this teaching include Paul of Samasota (third century) and Theodotus (c. 190). Theodotus the Cobbler—to distinguish him from the other Theodotuses in church history—arrived in Rome around 190 and began spreading adoptionist teachings. The church excommunicated Theodotus, and his followers floundered. Paul of Samasota was able to gain a little more traction due to his being bishop at Antioch. Around 260 he was declared a heretic for his adoptionist view in a synod at Antioch. Eusebius gives us the report: “The other pastors of the churches from all directions, made haste to assemble at Antioch, as against a despoiler of the flock of Christ.” It was in the course of dealing with his teaching in three different synods that the term homoousios came into play (much more on this term, which means that Christ is of the same essence as the Father, in Chapter 3).4

The views of these adoptionists are a subset of a larger group of heresies under the umbrella term of monarchianism, which refers to “one” ruler or one God. The monarchians put all the emphasis on the oneness of God. They were unable to see the other side, the three persons of the Godhead. They believed that the Bible teaches about Christ and even about the Holy Spirit. They understood these teachings, however, to refer to modes of being of the one God; Christ and the Holy Spirit were manifestations of this one God. They would speak of patripassionism, which literally means that God the Father (the Latin word is pater) was the one who was suffering on the cross (pathos or passion means “suffering”). Jesus Christ and God the Father are not separate persons, they said. Rather, Jesus Christ is a mere manifestation of God. One teacher of this heresy was Praxeas, known to us only through the writings of his opponent, Tertullian. Some think “Praxeas” to be a nickname.We know that he was a figure who arrived at Rome some time around 200. Another advocate of patripassionism was Sabellius, who also taught this view in Rome in the first two decades of the 200s. Sabellius was excommunicated in 217, but the movement he founded, known as Sabellianism, appeared in various places in the ensuing centuries.5

The views of the Ebionites and adoptionists were only the first ripples of the heresies that would deny Christ’s deity and would come to dominate the 300s. These views, however, seemed eclipsed by the damage done by controversies over Christ’s humanity. Pilate, in addition to identifying Christ as the King of the Jews, also rather insightfully said of Christ, “Behold the man!” (John 19:5; Ecce homo in Latin). Many, however, were not ready or willing to see him as truly in the flesh. “It is his flesh,” Tertullian would say, “that is the problem.” Thus, in the first and second centuries Christ’s humanity dominated the discussion. This makes sense given the philosophical climate of those first two centuries. Plato’s ideas dominated the intellectual world of both scholars and the populace alike. A fundamental doctrine of Platonic philosophy conflicts with the doctrine of the incarnation. For Plato, matter is bad, while the ideal is good. The body is bad, while the soul is good and pure. In Greek a catchy little jingle catches this well: Soma toma. Translated, it means: “Body, tomb.” If they’d had bumper stickers, this saying would have been on the chariots of the Platonist philosophers. For a Platonist, being in the flesh was not worth celebrating. Instead Platonists viewed the flesh as an inconvenient impediment that someday, when the body lies in the grave, will be overcome. Jesus coming in the flesh, the incarnation, embarrasses those who like their Platonism. His incarnation becomes quite the stumbling block.6

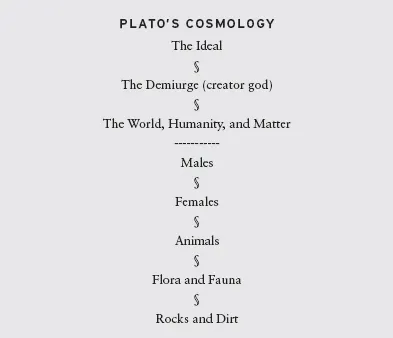

One of Plato’s more popular dialogues causes even more problems for the doctrine of the incarnation. In Timeaus, Plato takes a stab at explaining the big questions of life: Where did everything come from? Where did I come from? He answers by first running through mythological explanations such as the phoenix myth or the Atlantis myth, with most scholars understanding the Atlantis myth as Plato’s creative invention. Then Plato posits what appears to be his own explanation for the world and all things in it. Plato’s cosmology, or understanding of the world, starts with the abstract form, or what he prefers to call The Ideal. This Ideal, or God—but Plato would prefer to keep this figure impersonal and not personal—then created a buffer god, whom Plato calls the Demiurge, which means a creator god. The Demiurge in turn created all things. But even here there’s a flow chart. Plato thought males to be superior to females, females to be superior to animals, animals to be superior to flora and fauna, flora and fauna to be superior to stones and dirt. Matter is at the bottom of the chain, idea and the immaterial at the top. The farther down the chain, the lesser the value, the lesser the meaning.7

The biblical cosmology differs from Plato’s on another count. For Plato, this world of matter matters very little. As the physical body cages the human soul, the physical world cages the forms. Things represent instantiations of the forms, which represent The Form or The Ideal. Now this needs some unpacking. Again, at the top of the chain is The Ideal, the ultimate reality. The Ideal then is represented in various ideas or forms, like the forms of justice, beauty, or truth, or even the forms of personhood or of different animals. These forms then are represented in the world in individual, material things, like the things of laws, art, and science, or like the things of different human beings or dogs or cats.8

You might still be lost, so consider dogs as an example.There are many, many different dogs. Some are little, while some are large, like a Chihuahua versus a mastiff. Some are trained for certain functions, like herding animals or protection, while others seem destined to spend their days chasing their tails. Yet, all of these different creatures are all called dog. Plato explains this by arguing that all of these creatures are physical manifestations of the form of dog—they are all individual, material occurrences of the immaterial form or idea (although I don’t think he called it dogginess). When dogs cease to exist materially, the essence of the dog returns to the world of the forms. So it is with human beings. Of different colors, sizes, and shapes, all humans are material occurrences of the form of humanity. When we cease to exist in our physical lives, our souls reunite with the world of the forms.

Among the many implications of this understanding of the world stands the idea that this world matters little. This world functions as a vehicle back to the world of the forms. It is to be escaped from; it is to be overcome. Nothing of value comes from material things. Soma toma—the body is a tomb. The Bible poses a different worldview, a worldview that sees this world as having meaning, that sees the physical as a gift from God. When God surveyed the world he made, he pronounced it good, very good, in fact. The biblical creation account finds God grabbing a handful of dust and breathing into it, creating a being of matter and spirit with whom he desired to fellowship. And, due to humanity’s sin, Jesus, the divine son, humbled himself, took on flesh, and became human. Plato has no room for the incarnation. It belittles The Ideal to even consider having it take on flesh.

Now we see why the doctrine o...