eBook - ePub

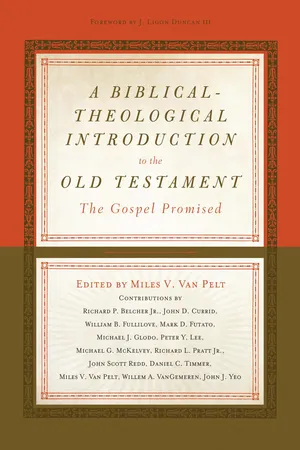

A Biblical-Theological Introduction to the Old Testament

The Gospel Promised

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The Old Testament is not just a collection of disparate stories, each with its own meaning and moral lessons. Rather, it's one cohesive story, tied together by the good news about Israel's coming Messiah, promised from the beginning. Covering each book in the Old Testament, this volume invites readers to teach the Bible from a Reformed, covenantal, and redemptive-historical perspective. Featuring contributions from twelve respected evangelical scholars, this gospel-centered introduction to the Old Testament will help anyone who teaches or studies Scripture to better see the initial outworking of God's plan to redeem the world through Jesus Christ.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access A Biblical-Theological Introduction to the Old Testament by Miles V. Van Pelt in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & Biblical Commentary. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Genesis

John D. Currid

INTRODUCTION

The name of the first book of the Hebrew Bible derives from the opening word of the Hebrew text, בְּרֵאשִׁית. This word means “in the beginning,” and it is an appropriate designation because the book is about beginnings: the beginning of the universe; the beginning of time, matter, and space; the beginning of humanity; the beginning of sin; the beginning of redemption; and the beginning of Israel. By deliberating over Genesis, then, we are essentially engaging in protology, the study of first things. That the cosmos has a beginning implies that it also has an end and that everything is moving toward a consummation (the study of these last things is called eschatology). The Scriptures, therefore, present a linear history, a movement from inception to completion.

Scholars have commonly tried to distinguish between this Hebraic view of history and that of other ancient Near Eastern cultures. Many have argued that the pagan cultures of the time believed in a cyclical history, teaching that nature is locked in an unending sequence of birth, life, death, and rebirth. And therefore, the world is heading nowhere; it is merely in a ceaseless, natural cycle. In reality, that contrast is too simplistic. The ancients were actually quite aware of history, which the great volume of historical records these peoples kept confirms. The ancient Egyptians, Assyrians, and Babylonians were skilled and proficient in preserving historical documents, annals, and chronologies.1 The contrast between the two conceptions of the universe really boils down to the question of what is the foundation of history. The Hebrews had a worldview that centered on God as the Lord and overseer of history. Everything that happens in the cosmos unfolds according to God’s plan; he is the One who moves history from a beginning toward a final climax (Isa. 41:4; 43:1–15; 44:6; 48:12). He is sovereign and sits on the throne of history. The other cultures of the ancient Near East had no such theological conception.

BACKGROUND ISSUES

Authorship

For the past 150 years, the question of the formation and development of the book of Genesis, and the rest of the Pentateuch for that matter, has dominated Old Testament studies. Inquiries into authorship, date of writing, and place of writing have stood at the very forefront of Old Testament scholarship. Although people have asked such questions throughout the history of Judaism and Christianity, perhaps the first to struggle seriously with the issues was Jean Astruc (AD 1684–1766), a professor of medicine at the University of Paris. Astruc determined that someone brought together four original documents to make up the Pentateuch. He noticed that certain names for God dominated different parts of the literature, and this became one factor in determining what belonged to which source. He also believed that doublets—that is, a second telling of the same incident—demonstrated different sources. Although Astruc likely believed that Moses was the author of each of the four sources, his studies laid the foundation for the biblical criticism that would soon follow.

So what started the belief that Genesis was the writing of not one person but rather various authors whose sources redactors (i.e., editors) stitched together over time? Perhaps the most important impetus for this notion was the thinking not of a biblical scholar but of a philosopher. Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (1770–1831) formed an influential worldview that argued that all things in reality are changing or in process. Everything is developing from lower to higher degrees of perfection. This process occurs by means of the dialectic that moves things from one state (thesis) to its opposite (antithesis) and finally achieves a higher synthesis between the two. It repeats itself so that higher states of existence come into being. This is a natural process that affects all areas of life: culture, social systems, political systems, biology, economics, and religion. It is an evolutionary view of existence.

One of Hegel’s colleagues, a biblical scholar named Wilhelm Vatke (1806–1882), took and applied Hegel’s philosophy to the study of the Old Testament and, in particular, to the formation of the Pentateuch.2 This marked a major turning point because “the application of Hegelian philosophy to the study of the Old Testament led to [Julius] Wellhausen’s [1844–1918] establishment of the modern Documentary Hypothesis of the Pentateuch and eventually to the death of Old Testament theology.”3 Building upon these foundational presuppositions of Astruc, Hegel, and others, subsequent biblical scholars theorized that the Pentateuch was indeed a collation of numerous sources brought together by later editors. However, they did not agree on the sources and how they were collated. For example, those who adhere to the Supplementary Hypothesis argue that there was one core document of the Pentateuch to which redactors added numerous fragments over the centuries. On the other hand, others argue that the Pentateuch lacks a core document altogether and consists merely of a mass of fragments from numerous sources that have been collated and edited (this is called the Fragmentary Hypothesis).

The major source theory developed in the nineteenth century was the Graf-Wellhausen Theory, otherwise known as the Documentary Hypothesis. This theory proposed four basic sources for the Pentateuch, referred to as J, E, D, and P:

- J is the Jahwist (or Yahwist) source. This is a source that primarily uses the name Jehovah (that is, Yahweh) to refer to God. The J source is considered the oldest source, and it can be viewed in Genesis 2:4–4:26, and in portions of Exodus and Numbers. The originators of the hypothesis thought that it had been derived from the period of the united monarchy during the reigns of David and Solomon.

- E is the Elohist source. It employs the name Elohim for God, and it comes from a later period than the J source. A later redactor, referred to as RJE, put the two sources together.

- D refers to the Deuteronomist. This material was written even later than the first two, and it was commonly seen as coming from the time of King Josiah in the second half of the seventh century BC. Another redactor, called RD, brought together this material with J and E to create one document.

- P is the Priestly and final source. It includes much of the cultic, sacred, and sacrificial material and matters related to the priesthood. Scholars who adopt the Documentary Hypothesis believe the P source was written late and should be placed during the exilic and postexilic periods.

While these are the four main sources for the Pentateuch, this position also argues that numerous smaller fragments, such as Genesis 14, were inserted into these primary documents.

Very few scholars today accept the Documentary Hypothesis as originally formulated; the issue of authorship has become much more complex. There is, in reality, little consensus among scholars regarding who wrote what and when, even though they continue to use the acronym JEDP. Additionally, many scholars argue that each of those four major sources resulted from various editors and redactors bringing together many other sources. What is clear is that much Old Testament scholarship denies the historicity of the material of the Pentateuch and claims that the material we do have is a result of centuries of literary evolution.4

Literary Analysis

In the last three decades, scholars from a variety of perspectives have called for a focus on the final form of the text as a literary whole. Standing at the forefront of this attention, Brevard Childs argued that exegesis should be based upon the final, canonical form of the biblical text.5 This perspective has led many scholars to shift their focus away from merely working in source criticism to discovering the various levels of how the Pentateuch reached its final form. Leading this charge is Robert Alter, who wrote a truly groundbreaking work titled The Art of Biblical Narrative.6 In this work, Alter defines a field of biblical study called literary analysis.

Literary analysis deals with what Alter calls “the artful use of language” in a particular literary genre.7 This includes such conventions in Hebrew writing as structure, wordplay, imagery, sound, syntax, and many other devices that appear in the final form of the text. In Alter’s own words, he defines it as follows:

By literary analysis I mean the manifold varieties of minutely discriminating attention to the artful use of language, to the shifting play of ideas, conventions, tone, sound, imagery, syntax, narrative viewpoint, compositional units, and much else; the kind of disciplined attention, in other words, which through a whole spectrum of critical approaches has illuminated, for example, the poetry of Dante, the plays of Shakespeare, the novels of Tolstoy.8

This literary approach has yielded much fruit in biblical studies, and it has allowed scholars once again to see the literary qualities of the final form of a text.

For example, when source critics engage a text like Genesis 38, the account of Judah and Tamar, they understand it as a mixture of source documents dominated especially by J and E, and many see no connection between this story and the surrounding account of Joseph’s life. For example, von Rad argues in his Genesis commentary that “every attentive reader can see the story of Judah and Tamar has no connection at all with the strictly organized Joseph story at whose beginning it is now inserted.”9 Speiser agrees when he says, “The narrative is a completely independent unit. It has no connection with the drama of Joseph, which it interrupts.”10 Genesis 38 is, therefore, a mere interpolation, probably inserted by the J or Yahwist author.

Literary analysis, however, demonstrates something different. It asks, why has the story been placed here? And it concludes, in this case, that the text of Genesis 38 has been masterfully and artistically woven into the context of the Joseph story. For example, Sprinkle, summarizing Alter, observes that the same motifs occur in chapter 38 as in chapter 37:

As Joseph is separated from his brothers by “going down” to Egypt, so Judah separates from his brothers by “going down” to marry a Canaanite woman. Jacob is forced to mourn for a supposed death of his son, Judah is forced to mourn for the actual death of two of his sons. . . . Judah tricked Jacob, so Tamar (in poetic justice) tricks Judah. . . . Judah used a goat (its blood) in his deception of Jacob, so the prom...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Foreword

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Abbreviations

- Introduction

- 1. Genesis

- 2. Exodus

- 3. Leviticus

- 4. Numbers

- 5. Deuteronomy

- 6. Joshua

- 7. Judges

- 8. 1–2 Samuel

- 9. 1–2 Kings

- 10. Isaiah

- 11. Jeremiah

- 12. Ezekiel

- 13. The Twelve

- 14. Psalms

- 15. Job

- 16. Proverbs

- 17. Ruth

- 18. Song of Songs

- 19. Ecclesiastes

- 20. Lamentations

- 21. Esther

- 22. Daniel

- 23. Ezra–Nehemiah

- 24. 1–2 Chronicles

- Appendix A: The Seventy Weeks of Daniel 9

- Appendix B: The Role of Heavenly Beings in Daniel

- Contributors

- General Index

- Scripture Index