- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Many believers worry that science undermines the Christian faith. Instead of fearing scientific discovery, Jack Collins believes that Christians should delight in the natural world and study it. God's truth will stand against any challenge and will enrich the very scientific studies that we fear.

Collins first defines faith and science, shows their relation, and explains what claims each has concerning truth. Then he applies the biblical teaching on creation to the topics of "conflict" between faith and science, including the age of the earth, evolution, and miracles. He considers what it means to live in a created world. This book is for anyone looking for a Christian engagement with science without technical jargon.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Science and Faith? by C. John Collins in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & Christian Theology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

SECTION II

THEOLOGICAL ISSUES

4

THIS IS MY FATHER’S WORLD

The Biblical Doctrine of Creation

THE FIRST BIG QUESTION of life is, Who or what made you? How we answer this basic question will decide for us what makes life meaningful or worthwhile.

The purpose of this chapter is to discuss the biblical teaching about the world as God’s creation. Since this leads us into a discussion about how God continues his involvement in the world, we will also touch on the biblical teaching about providence—but the fuller discussion of that topic will come in a later chapter.

Most people, when they hear that a discussion is about “creation,” assume you’re talking about the days in Genesis 1 and the age of the earth. I don’t believe that such issues are at the heart of the biblical teaching, but I will of course address them since they are controversial and divisive. However, I will do so in the three chapters that follow this one, and I will focus here on the conclusions from Genesis 1 and 2 that should unite all Christians. I will focus on Genesis 1:1–2:3, and leave most of the details of 2:4-25 until my chapter on human nature.

HOW MANY CREATION ACCOUNTS DOES ONE RELIGION NEED?

LITERARY RELATIONSHIPS OF GENESIS 1 AND 2

LITERARY RELATIONSHIPS OF GENESIS 1 AND 2

We often find people referring to Genesis 1 and 2 as the “creation accounts,” implying that they think these are two stories about the beginning, each having a separate origin, a different purpose, and conflicting details. I want to show you why I think that it’s better biblical interpretation to see them as two accounts that support each other: Genesis 1 gives you the big picture, while Genesis 2 fills out the details of the sixth day of Genesis 1.

I don’t think anyone disputes the idea that there are two narratives; what they dispute is where one ends and the other begins, and how the events of the one relate to those of the other. So let’s begin our study by seeing what the boundaries are of the different stories.

To follow along, you will be best off if you use the ESV for your Bible. If you have a NASB or RV, you will be able to see most of what I’m saying, and I’ll comment on the differences without getting technical.

We don’t have any problem with where the first story begins: “In the beginning. . .” Nor do we have a problem seeing that it covers six days of God’s work, with a seventh day being his day of rest, his Sabbath. The real difficulty is whether the first story ends with 2:3 (God resting on his Sabbath), or with 2:4a (“These are the generations of the heavens and the earth when they were created,” which would round off the narrative by summing it up and pointing back to 1:1).

The second approach to division—taking the first story as 1:1–2:4a—is pretty common, among both commentaries and Bible translations such as NAB, NRSV, and CEV. The NIV and REB divide 2:4, but put both halves in the second narrative. The NKJV does not divide the verse, but makes the whole verse an introduction to the sentence that continues through verse 6.

The reasons why we should not divide the verse at all, but should treat it as a separate sentence, as ESV and NASB do, are apparent once we set it out in poetic lines:

These are the generations of the heavens and the earth when they were created, in the day that the LORD God made earth and the heavens.

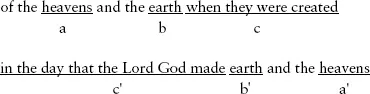

The phrase “these are the generations” appears ten other times in Genesis (5:1; 6:9; 10:1; 11:10, 27; 25:12, 19; 36:1, 9; 37:2), and each time it marks the beginning of a new section. It is reasonable to expect it to do the same here—or at least we need a good reason not to find it doing so. Further, the lines “of the heavens and the earth when they were created” and “in the day that the LORD God made earth and the heavens” actually form an elaborate mirror pattern (called a chiasmus):

In this pattern the elements have the order a-b-c || c'-b'-a', that is, the second line mirrors the first in its order of elements. Scholars of the ancient Near East often feel good when they can show a chiasmus with two elements in a passage (a-b || b'-a'), though it may be chance rather than art that produced it. But when there are three elements, that’s taken as clear evidence of art—which means the author wanted you to notice it. And what was the author telling you to do once you noticed it? He wanted you to read it as a whole thought, without breaking it apart.

Another feature shows that the author was also telling you to harmonize the two stories: the name of God in 1:1–2:3 is just “God,” while in 2:5–3:24 he is “the LORD God.” The name “God” is the title of the deity in his role as Creator and Ruler of the world; and the name LORD (Hebrew Yahweh or Jehovah) is his personal name, the one that he uses in entering into a relationship with humans (see Ex. 3:13-15, where God himself explains it). Now if we read this verse in cooperation with our author, we will see that he wanted us to see that “God” of 1:1–2:3 is the same being as “the LORD God” in 2:5–3:24—in other words, the covenant God of Israel (“the LORD”) is the Maker of heaven and earth (“God”).

There is plenty more to say about Genesis 2:5-7, and I will touch on more details in the next chapter. For now I will quote these verses from the ESV and make a few comments:

5 When no bush of the field was yet in the land and no small plant of the field had yet sprung up—for the LORD God had not caused it to rain on the land, and there was no man to work the ground, 6 and a mist was going up from the land and was watering the whole face of the ground— 7 then the LORD God formed the man of dust from the ground and breathed into his nostrils the breath of life, and the man became a living creature.

You can see from this version that verses 5 and 6 give you the setting for what happened in verse 7. That is, at some particular time before the rain fell on the ground to make the plants grow, while a mist (or rain cloud) was coming up and watering the land, God formed the man. As we will see when we compare these verses with Genesis 1:1–2:3, the event of 2:7, 21-22—the making of the first man and woman—is the same as that of 1:27, but told more fully. This helps us to see that the way to harmonize the two stories is to see 1:1–2:3 as the overall narrative, while 2:4-25 fills in lots of particulars of the sixth day. This will come in handy when, in the next chapter of this book, we decide what to do with the days of Genesis 1.

OUTLINE OF GENESIS 1:1–2:3

The outline of Genesis 1:1–2:3 will help us find its purpose. Without too much trouble we can see that it is as follows:

1:1-2 Preface (background actions and information)

1:3-5 Day 1 (light and darkness)

1:6-8 Day 2 (sea and sky)

1:9-13 Day 3 (land, sea, vegetation)

1:14-19 Day 4 (light-bearers)

1:20-23 Day 5 (sea animals and flying creatures)

1:24-31 Day 6 (land animals and humans)—the longest day

2:1-3 Day 7 (rest and enjoyment)—no refrain

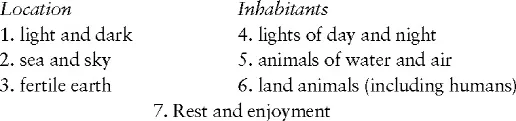

Another way to look at the account is to see it as giving us three days of setting up locations, and then three days of making the inhabitants for those locations, followed by the day of rest:

Each of the six workdays begins with “and God said,” and ends with the refrain, “and there was evening and there was morning, the nth day.” (I know that the King James Version has “and the evening and the morning were the nth day” for the refrain; but this is a mistranslation, apparently inherited from the Latin version of the fourth century A. D. The Greek version of the third century B. C. had it right, and most modern translations give the correct rendering. )

The seventh day is different, because God doesn’t “say” anything and he doesn’t “do” anything—he’s “resting”—and because there is no refrain about the evening and the morning.

WHAT IS GENESIS 1:1–2:3 ABOUT?

If we are to know how to make use of this passage, we need to know what it is about. As C. S. Lewis said so well,

The first qualification for judging any piece of workmanship from a corkscrew to a cathedral is to know what it is—what it was intended to do and how it is meant to be used.

The first thing to say about Genesis 1:1–2:3 is that it is part of Genesis 1–3, which in turn is part of Genesis 1–11, which in turn is part of Genesis—which is the first of the five books of Moses. The books of Moses are about how God called Abram to be his friend, and promised that he would make of Abram a mighty nation—a nation that would be God’s treasured possession. But the promise was never for the nation alone; it always had in mind “all the families of the earth” (Gen. 12:3). So the books of Moses are about how God fashioned a people for himself, through whom he would bring blessing to the rest of the peoples (which is what the apostles carried out).

Genesis 1–11 sets the stage for this special call to Abram. In it we learn of the one God who made everything there is (Gen. 1:1–2:3), and who had a special plan for mankind (Gen. 2:4-25). Mankind fell into sin (Genesis 3), and then began to disperse over the earth (Genesis 4–5). The stories of the flood (Genesis 6–9) and of the Tower of Babel (Genesis 11) are similar: all mankind are accountable to the same God, the very one who made the world and mankind; and with such power no one can stop him from bringing about his righteous judgment. But all mankind are his—so the plan for Abram looks forward to restoring all mankind to a right standing with God.

You will find that many writers call Genesis 1:1–2:3 a cosmogony, meaning a story about how the universe came to be (cosmo- for the cosmos, -gony for the origin). I would say that this description is only partly true, and really misses the point. The cosmogony part gets taken care of in verse 1 (“in the beginning God created the heavens and the earth”), and then the narrative moves on to its main point, the making and preparing of the earth as a place for humans to live. We can see this if we make the following observations.

First, let’s consider the relationship of verses 1-2 to the rest of the account. I take verse 1 as describing the initial creation event. Some think it is actually a summary of the whole account, but I don’t think that can work: as we’ll see shortly, other Bible writers took this verse as describing creation from nothing; and if the verse is a summary of the account, then it’s noncommittal on whether creation took place from nothing. I prefer to go with the other Bible writers. Besides, the first day begins in verse 3 (with “and God said”), and verses 1-2 are background—they describe the setting of day one. The most usual function of the kind of background statement you have in verse 1 is to give an action that took place some unspecified time before the narrative actually gets under way (as in Gen. 16:1; 21:1; 24:1).

All this means that the origin of the whole show gets taken care of in one verse, and the author moves on to focus on something else.

Second, the words “heavens” and “earth” in verse 1 refer to “everything”; but after verse 2 they get narrower in their meaning: “heavens” narrows to “Sky” (see v. 8, ESV margin), and “earth” narrows to “Land” (see v. 10, ESV margin). This tells us that the author has narrowed his focus from the whole universe down to planet earth.

Third, the high point of the narrative is the sixth day (which gets the longest description), and especially verse 27, the making of mankind. You can see this by the repetitive structure of the verse: “So God created man in his own image,” repeated as “in the image of God he created him,” and followed by “male and female he created them”: three statements of the same event. The effect of this repetition is to slow you down and make you mull over what the verse says, and what the event means. This is because mankind is the crown of God’s creation week.

So the focus on the making of the earth’s different environments and inhabitants reaches its peak at the making of the humans who are to rule over the whole earth. The earth is a good place for these people to live, love, work, and worship God.

IS GENESIS 1:1–2:3 SUPPOSED TO BE A HISTORICAL RECORD?

To answer this question, we have to be able to say what we mean by the word “historical.” (We’re back to the meanings of our terms again!) In ordinary language, “history” means “the things that happened in the past”; and therefore to say that a story is “historical” is to say that the author wants you to believe that he is telling you about events that actually took place.

We have to clarify this, because for some scholars, “history” means a narrative that does not involve God as doing anything. This is a ridiculous specialized use of a word that has a perfectly reasonable ordinary meaning, and could lead to such odd assertions as, “this account is not ‘historical,’ but I’m not saying it didn’t happen.” I think more often, though, people hear the word “historical” as meaning that the account tells you its events in just the order in which they happened, or that it’s a complete record, or that there are no figurative elements in it. When we use the word “historical,” though, we are not committing ourselves to anything of the sort. Otherwise, how could we call Psalm 105 a “historical” psalm—does the fact that in verses 28-36 it tells the events of the exodus in a different order than the book of Exodus does, and leaves out some of the plagues, mean that it’s not “historical”? This doesn’t make any sense to me, so I’ll stick with the ordinary meaning of the word (the author wants you to believe that he is telling you about events that actually took place) and not read into it what isn’t there.

Now then: did the author mean us to take Genesis 1:1–2:3 as history? The answer is certainly yes, for two reasons. The first is its place in the book of Genesis, a book that is concerned with historical matters: it starts the whole thing off and explains why things are the way they are. Obvious evidence for this is the genealogies that run through the book: they connect later people with those ea...

Table of contents

- COVER PAGE

- TITLE PAGE

- COPYRIGHT

- CONTENTS

- ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

- SECTION I

- SECTION II

- SECTION III

- SECTION IV

- APPENDICES

- APPENDIX A

- APPENDIX B

- APPENDIX C