Some of the gadgets in the toolbox are age-old, some of them thoroughly modern. It’s certainly not true to say, for example, that options are new-fangled. They date back at least to the Middle Ages, and possibly to before that. What is newer is our understanding of how they work and the development of systems by which they can be freely traded.

In fact, trading in futures and options over commodities probably dates back a long way in history – perhaps as far back as the start of systematic agriculture. Certainly it goes back long before the establishment of joint stock companies and the notion of trading shares in them on exchanges.

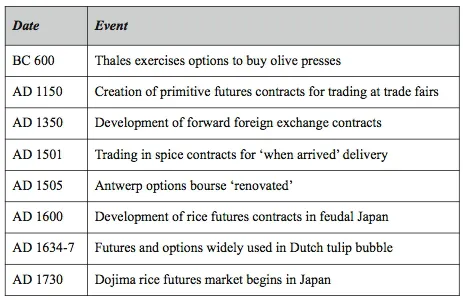

Let’s take just a few episodes in the history of derivatives to illustrate this point.

Early days

Wags in the derivatives market reckon that the first recorded futures transaction was in the Bible – when Esau sold his birthright for a mess of pottage. An alternative biblical analogy was Jacob entering into a contract to exchange his labour for the hand of Rachel.

Opinions differ about whether this was a future or an option. Jacob laboured for the right to marry Rachel, but maybe did not have the obligation to – a crucial distinction. Some view it as a swap – his labour in exchange for marrying his girlfriend.

In Ancient Greece, Thales – a shrewd merchant – forecast a bumper olive crop. Rather than speculate on a fall in the price of olives or olive oil, he came to the conclusion that olive presses would be in short supply. Since he had only limited capital, he decided to arrange to pay a deposit for the right to buy some presses.

When the harvest came in he could, if things worked out, pay the balance and buy the presses. Or if things didn’t happen as planned, he would be able to walk away, losing only his deposit. History suggests he was right. He cleaned up when a bumper harvest occurred and the owners of olive groves clamoured to use the presses he controlled. This seems to be the first recorded instance of the use of what we now term a call option.

The next step in the story dates from the 12th century. In Southern Europe at that time, trade fairs had developed. They allowed the cities of Florence and Venice, as well as other northern Italian towns, to participate in trade with cities in France, Belgium and the Netherlands.

Whether it was for convenience, or more likely because they didn’t trust each other, the trade fairs began to revolve around codes of conduct that developed into elementary contracts. The contracts were agreements to exchange goods in the future based around samples available to be inspected on the spot. These forward delivery agreements – known as lettres de faire – were originally just between one merchant and another, but eventually came to be traded more widely among the merchants. Eventually some merchants began trading just the contracts rather than the underlying commodities.

Table 1.1 – Ancient derivatives history timeline

Forward foreign exchange transactions were first recorded in the 14th century. London branches of Italian banking houses had contracts with the Papal Nuncio in England to remit papal taxes gathered in England. The rates for these exchange transactions, though not the precise amounts involved, were set a year in advance.

Some types of futures or forward contracts developed in their earliest serious form in the early 16th century. In 1501 the King of Portugal used Antwerp as the port in which to sell spices which his ships were bringing from the Indies. Merchants competed for the contracts. They paid in advance for spices to be delivered when the fleet arrived. The delay between setting the price and the delivery date meant the contracts were, like present-day futures, speculative and very volatile in price.

In 17th century Japan, serfs who leased their land from the local noblemen were allowed to pay rent in the form of a portion of the following year’s harvest. Contracts were issued to the nobleman and secured against the collateral of the rice harvest. Eventually, a century or more later, the contracts themselves came to be standardised and traded through a rudimentary exchange – the Dojima market. The noblemen sold these rights to the crop in case bad weather or warfare reduced its value.

As an aside, one of the more arcane forms of technical analysis, known as candlestick charting, developed around the same time. Traders used it to attempt to predict prices from past history. It is still used today, as the chart below shows:

Figure 1.1 – Candlestick charting of Vodafone’s share price

© Winstock Software

In the 16th and 17th century, options – at that time called premium transactions – were also being developed more systematically. One origin of the use of options was by sea captains venturing to the East Indies. They sold options on part of their expected cargo to merchants in Amsterdam and Antwerp in order to finance the voyages. The risk that the boats would not return fully laden, or might sink, was thus transferred in part to the buyers of the options.

Shakespeare seems to have had much the same in mind in the Merchant of Venice, whose plot turns on the fortune of Antonio’s ships (argosies, or ‘bottoms’ in the jargon of the time). As a good venture capitalist, Antonio diversified his risk, sending several ships to different destinations As he said –

‘My ventures are not in one bottom trusted, nor to one place; nor is my whole estate upon the fortune of this present year. Therefore my merchandise makes me not sad.’

Rather than pay interest to Shylock when his ships were overdue, Antonio contracted to borrow three thousand ducats for three months. Instead of interest Shylock agreed to take an option over a pound of Antonio’s flesh –

‘If you repay me not on such a day and in such a place, such sum or sums as are expressed in the condition, let the forfeit be nominated for an equal pound of your fair flesh, to be cut and taken in what part of your body pleaseth me.’

We can argue whether or not this is a bond with a particularly unpleasant conversion right, or some form of option. Either way it shows that forms of derivative were used to finance trade in Shakespeare’s day. In the end Shylock went to court to enforce the contract, but Antonio’s ships came home in the nick of time.

The most authoritative documentation of the use of options comes in the Dutch tulip bubble in the early 16th century. What began as a normal trade among growers, gardeners and collectors snowballed into a boom of epic proportions. As Peter Bernstein records in his book Against the Gods –

‘Much of the famous Dutch tulip bubble involved trading in options on tulips rather than in the tulips themselves; trading that was in many ways as sophisticated as anything that goes on in our own times.’

Bernstein says that new research shows that tales that options fuelled the boom are wide of the mark. They simply allowed more people to participate in a market that had hitherto been beyond their reach.

Figure 1.2 – The subject of ‘tulipomania’

‘The opprobrium that attached to options during the so-called bubble was in fact cultivated by vested interests who resented the intrusion of interlopers onto their turf.’

However, Charles Mackay’s classic book, Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds, suggests otherwise. As prices began to fall, he describes how the derivatives used by everyone by that time exacerbated the situation.

‘A had agreed to purchase ten Semper Augustines from B at 4000 florins each, at six weeks after the signing of the contract. B was ready with the flowers at the appointed time; but the price had fallen to three or four hundred florins, and A refused either to pay the difference or receive the tulips.’

Speculation of different forms was also rife. Dutch currency dealers entered into bets on exchange rates, based on percentage movements up or down, and settled their debts by transferring the margin between the loser’s speculation and the actual rate. This looks like an early form of contract for difference (CFD).