Chapter 1. How and When Sovereign Wealth Funds Came About

The history of sovereign wealth funds can be divided into four phases, beginning in 1953. In that year, the first authority that foreshadowed a SWF was founded: the Kuwait Investment Authority (KIA). From then on, SWFs, new entities in finance and the world economy, grew and spread throughout various countries. SWFs were to assume three basic features: they originated from foreign currency surpluses; they were owned and managed by sovereign states or their emanations; and they were financially earmarked mainly for extra-national purposes.

According to analysis by Griffith and Ocampo , the accumulation of foreign-exchange assets and the subsequent decision to establish a SWF is typically based on four types of motives:

- ‘wealth substitution’ or transforming natural resources into financial assets

- ‘resilient surplus’, in case of long-lasting current account surpluses that cannot be corrected in the short-run by exchange-rate appreciation

- ‘counter-cyclicality’, to absorb temporary current account surpluses and/or booming commodity prices

- ‘self-insurance’, associated with reducing the risks of pro-cyclical capital flows.

The last two strategies, even if rational from the point of view of the individual country, help fuel global imbalances and the consequent instability of the world economy. As we will see, in each of the phases in the development of SWFs, the above motives have had different relative importance. This has given rise to different types of SWFs in terms of origin, nature and purpose, and consequently in their investment strategies.

The initial phase that started in 1953 intensified in the 1970s, with the start-up of several SWFs in countries with surpluses from oil exports (which grew with the increase in the price of crude oil, and continued until the first half of the 1990s). In this period, the motives for creating most of the funds were wealth substitution and counter-cyclicality.

The second phase began in the late 1990s and ended in 2004. In addition to the oil SWFs, there were growing numbers of SWFs emerging from Asian countries, which benefited from enormous trade-balance surpluses from exports of manufactured goods. By accumulating and managing currency reserves, these SWFs pursued a strategy of covering the risks from the kinds of financial and currency crises which had characterised their recent past (self-insurance).

The third phase covered the recent years from 2005 to 2008, when the term ‘sovereign wealth funds’ was first coined and SWFs came to the attention of the broader public (and not just financial operators). In this phase we also saw a change in the attitude of countries receiving SWF investment: from caution if not hostility towards SWFs, to appreciation as lenders of last resort able to help them resist banking and financial turmoil.

The financial crisis beginning in 2007 opened a fourth phase that was still underway in 2010. In this phase, SWFs have had to come to terms with significant losses, and financial markets in difficulty everywhere. This has caused their investment activity to substantially contract. Only since the second half of 2009 have they really returned to the fray, with targets and strategies adjusted to the changed financial scene. They have proven, so far, to now be major players in international financial markets, willing to behave responsibly and cooperatively.

From 1953 to the Mid-1990s: Unknown Actors

This first phase has two milestones. The initial one came in 1953 with the establishment of the Kuwait Investment Board, which then became the Kuwait Investment Authority (KIA). This was actually not a real SWF, but an authority, according to the criteria listed in Chapter 2. Nevertheless, KIA was in substance a SWF, because its specific purpose was to invest surpluses derived from oil revenues so as to reduce Kuwait’s dependence on exhaustible fossil reserves, thus lessening the effects of price oscillation. Thus oil revenues were converted into financial investments; mostly fixed-interest, low-risk securities.

The second SWF, established with a specific legal status, was created by the British colonial administration of the Gilbert Islands in 1956, to capitalise on the revenues from phosphate by investing them in diversified shareholdings. The Revenue Equalization Reserve Fund was and is certainly not comparable in size to those generated by oil revenues or other revenues mentioned later. But compared to the size of the economy of its host (now the Republic of Kiribati), the stock of assets accumulated by this SWF is in the present-day three times greater than their GDP.

In the 1970s the rise in the price of oil from under US$5 a barrel to more than US$35 in 1980, the year after the Khomeini revolution, made it possible for exporting countries to rapidly accumulate enormous financial wealth. These revenues were partly spent domestically, with the resulting push of domestic inflation. Consequently oil revenues were increasingly allocated to foreign direct investment. We can see in this accumulation of foreign assets and the subsequent decision to establish SWFs with them, the prevalence of wealth substitution and counter-cyclical motives. The purpose indeed was to create diversified sources of income other than oil, in order to counterbalance the depletion of this raw material and its price fluctuation, but also to protect domestic wellbeing. An additional motive might have been political, too, as governments in emerging oil-exporting countries often need to maintain control of wealth in order to strengthen their internal political power as well as gain support from developed countries interested in receiving petro-dollar investment.

Various countries, in particular the members of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC), launched new SWFs: the United Arab Emirates (UAE) established the Abu Dhabi Investment Authority in 1976, and in the same year Kuwait founded another fund, the Future Generations Fund, which was managed by KIA.

Even in developed countries, the increase in oil prices and prices of raw materials in the early 1970s brought about the launch of two oil-based SWFs in 1976: the Alaska Permanent Fund Corporation in the United States, and Alberta’s Heritage Fund in Canada.

In this phase, another type of SWF was also established: the non-commodity SWF. In 1974 the Singapore government founded Temasek Holdings, while in 1981 the Government of Singapore Investment Corporation (GIC) was also set up. Both fitted into Singapore’s growth strategy, as a city-state with too small a domestic market to generate sufficient consumption and investment demand to use its currency and fiscal surpluses. Of a similar nature, Malaysia’s Khazanah Nasional Berhad was set up several years later in 1993.

The 1980s and 1990s featured two large-scale international dynamics which affected SWFs: a fall in the price of oil in the 1980s and the wave of growing globalisation in the 1990s.

The oil price fell below US$20 a barrel in the mid-1980s, staying below this level until the end of the 1990s except for a price upsurge during the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait. These downward price fluctuations reinforced the belief of governments running SWFs that their income should not depend solely on oil and natural gas. This meant reinforcing the counter-cyclical component at the base of the decision to establish SWFs. Thus other SWFs were launched, including the State General Reserve Fund of Oman in 1980, and, in 1981, the Libyan Arab Foreign Investment Company, fuelled by proceeds from natural gas fields discovered in the 1970s and 1980s. In 1983, the Brunei Investment Agency was established, and in 1984 so too was the Abu Dhabi International Petroleum Investment Company.

The advent of globalisation contributed significantly to the growth of SWFs, facilitating the international movement of capital and direct investment abroad. The year 1990 was the second great milestone in the initial phase of SWF history, with the establishment of the Norwegian Government Pension Fund, currently the second-largest SWF in the world. This initiative must be seen as an answer to the needs of wealth substitution and counter-cyclicality, as well as an attempt to avoid ‘Dutch disease’. (Dutch disease being the fate which befell a Holland briefly rich with North Sea natural gas in the 1960s. The currency of the commodity-rich nation rose too far, distorting the economy.) Indeed, in the case of an advanced country like Norway, it makes economic sense to prefer long-term savings to domestic spending on internal investment.

During this first period, spanning more than 40 years, 16 SWFs (refer to the classification provided in Chapter 2) were established. Their investment strategies remained conservative and prudent with portfolios largely composed of low-yield, mainly US government securities. In this period they sought and maintained a very low profile. As a consequence they were almost unknown even to the financial community.

From the Late ’90s to 2004: Emerging From Anonymity

Emerging countries’ impressive accumulation of foreign exchange reserves was a characteristic phenomenon of the first decade of the 2000s. Following the currency crisis that hit emerging economies in the 1990s (particularly in the latter half of the decade), many countries, and especially those hardest hit, proceeded to systematically accumulate reserves well in excess of short-term external liabilities (the level suggested by the so-called Guidotti-Greenspan rule).

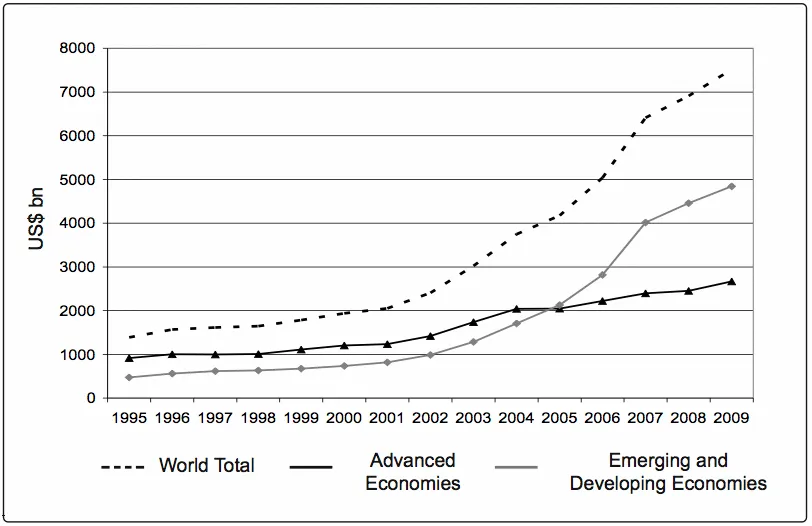

Figure 1 – Total foreign exchange holdings in US$ billion (1995 to third quarter 2009)

Source: Our elaboration on IMF, Currency Composition of Official Foreign Exchange Reserves (COFER) Database, accessed February 2010.

Self-insurance is one of the most commonly accepted explanations of why developing countries decide to hold an excessive level of foreign reserves with all the costs this choice implies . Another possible explanation is mercantilism (fostering export competitiveness). For some countries the rationale of hoarding reserves stems from an aggregation of several motives: in the aftermath of the East Asian crisis self-insurance dominated, while after 2000 other motives must also be taken into account .

Just after the various financial crises of the late ’90s, emerging countries, facing growing financial instability in a more interconnected world, rationally decided to self-insure themselves to avoid having to resort to the IMF with its principle of conditionality, thus minimising the risks and associated costs of future crises. Excess reserves may therefore be correlated with the volatility of capital flows and eventually to the level of a country’s financial openness. Obstfeld et al have conducted an empirical study that clearly shows a statistical and economically significant correlation of reserve levels with financial openness and financial development, especially in the years after the Asian crises. Indeed, countries that gradually liberalised capital markets have been less exposed to financial crises. If hoarding reserves is a rational answer from an individual country’s point of view, however, from the collective point of view this strategy appears dangerous, since it contributes to feeding global imbalances, with some countries accumulating large debts and others accumulating excessive currency-exchange surpluses.

Since this huge level of reserves generates two types of costs both in terms of lower yields and the sterilisation necessary to avoid inflation, the debate in economic literature is open as to why countries choose to self-insure themselve...