![]()

1. The Declining Everything

The world we wake up to every morning is so different from the one many of us grew up in. Take inflation – something that in my childhood was as certain as the sun rising every morning; however, you cannot take it for granted anymore. Come to think of it, there are many things you cannot take for granted anymore. I look at why that is or, at the very least, I begin to scratch the surface in my search for answers.

Why we are slowing down

Everything is slowing down. Economic growth is in a multi-decade decline. Productivity growth is losing momentum, and has even turned negative in some countries. The same goes for workforce growth. Inflation turned into disinflation at first but, more recently, the F-word of economics – deflation – has popped up in more and more countries.

What on earth is going on?

Ever since the Global Financial Crisis nearly took us all down, financial commentators and research analysts have spent a lot of time trying to explain to a puzzled financial community why economic growth remains pedestrian, why inflation is so low, and why interest rates are stuck in the quicksand.

An endless flow of research papers has addressed the subject, collectively blaming many causes. I shall not list every single reason I have come across over the years; suffice to say that the following six reasons – or some variety of those – probably cover most that I have seen:

1. A statistical mirage

Argument: There isn’t a problem. Smartphones replacing cameras, etc., underestimate actual economic growth.

2. A hangover from the Global Financial Crisis

Argument: Severe financial crises make recovery from a downturn even more difficult.

3. Secular stagnation

Argument: Reduced population and workforce growth, lower prices for capital goods, and the nature of recent innovations (e.g. online shopping replacing brick and mortar shops) all hold back economic growth.

4. Slower innovation

Argument: The pace of innovation has declined; almost everyone now benefits from the things that matter the most to productivity – e.g. electricity and transportation – and recent innovations are more marginal in nature in terms of economic benefits.

5. Policy missteps

Argument: An increase in government spending combined with tax hikes (which is a policy pursued by many governments in recent years) has had a strong negative impact on private investment spending.

6. Abusive behaviour

Argument: Abuse of market power, monopoly status, etc., have contributed to the slowdown in wages and output.

None of those six suggestions provide a satisfactory explanation for the stagnation conundrum, though. They have all played a role – some more than others – but not one deserves to be credited as the main reason.

The facts

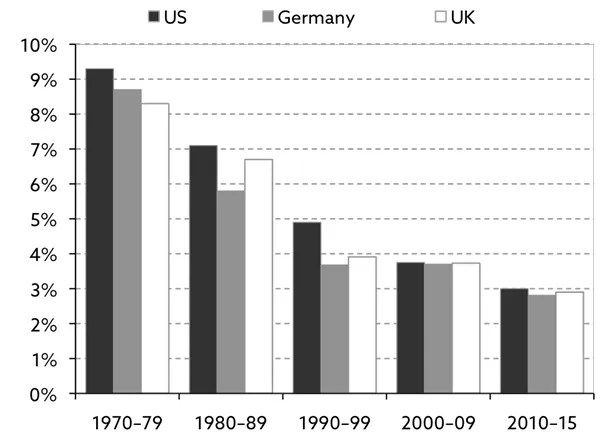

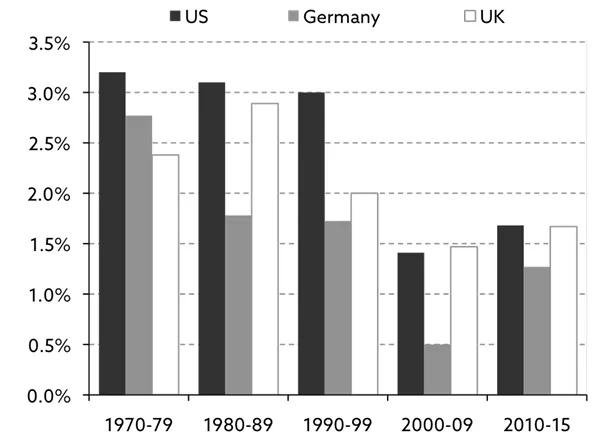

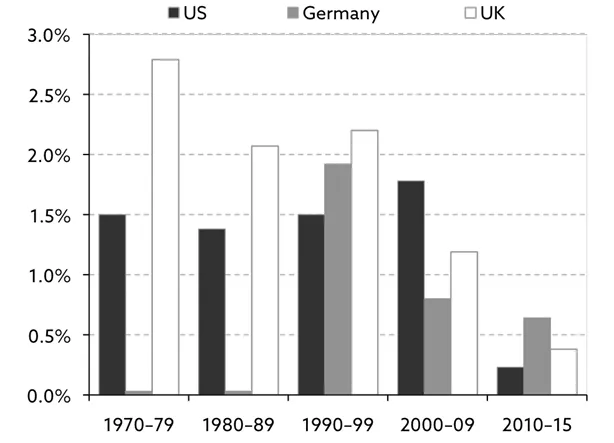

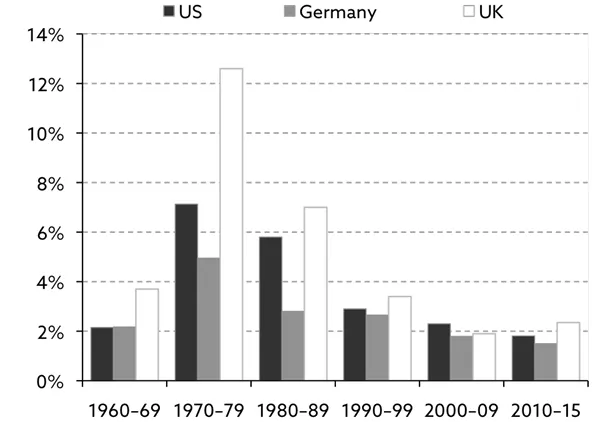

To fully understand what is going on, I suggest you take a good look at the following four exhibits (1.1.1–1.1.4). As you can see, GDP growth, in both nominal and real terms, productivity growth and inflation have all trended down for a very long time – by most accounts since the 1970s – so something very fundamental must be astray.

Exhibit 1.1.1: Nominal GDP growth by decade (compound annual growth rate, CAGR)

Exhibit 1.1.2: Real GDP growth by decade (CAGR)

Exhibit 1.1.3: GDP growth per hour worked by decade (CAGR)

Exhibit 1.1.4: Average annual inflation by decade (CPI)

Source: Strategic Economic Decisions (2016).

A very simple way to measure GDP growth

Let’s begin our journey with something very basic.

What is it that drives economic growth?

At the most fundamental level, economic growth is driven by only two factors – the total number of hours worked on an aggregate basis and the output per hour, the latter of which is effectively a measure of how productive the workforce is.

There are no reliable statistics for the total number of hours worked, but thankfully the workforce put in roughly the same number of hours from one year to the next, so the size of the workforce is a good proxy for the number of hours worked. The relationship can be expressed as follows:

∆GDP = ∆Workforce + ∆Productivity

JP Morgan Asset Management has tracked how much the two components have contributed to GDP growth in the US over the last 60 years (exhibit 1.2) and, as one can see, US workforce growth has been in decline since the mid-1980s.

Meanwhile, productivity growth, as measured in exhibit 1.2, confirms the picture from exhibit 1.1.3, i.e. that the decline in productivity growth is of more recent date. Both of those charts are based on labour productivity, which is the measure of productivity that most focus on; however, there is a problem. Labour productivity will rise sharply if sufficient money is spent on new machines, but that doesn’t necessarily improve overall economic efficiency.

Consequently, the concept of total factor productivity (TFP) was conceived. It is calculated as the percentage increase in output that is not accounted for by the changes in the volume of inputs of capital and labour. In other words, TFP is a measure of what share of increased productivity can be explained by factors other than growth in labour or capital.

Over the past half century, almost two-thirds of the growth in TFP can be explained by technology improvements. It is a better proxy for an economy’s return on capital, but it wouldn’t be fair to simply replace labour productivity with TFP. They are two very different measures of productivity. Furthermore, and as you will see over the coming chapters, declining TFP g...