Chapter 1. Luke: The Big Picture

The scarcest resource for successful investors is not money but attention: how to manage the trade-off between time and rationality to best effect. There is not time in life to find out everything about every potential investment. Investment skill consists not in knowing everything, but in judicious neglect: making wise choices about what to overlook.

Top-down investors (geographers) start from the big picture and work down: they think first about macroeconomic themes such as interest rates and commodity prices, and only then look for individual companies aligned with those themes. Bottom-up investors (surveyors) start from lots of small pictures and work up: they think first about the attributes of individual companies, and only then note any macroeconomic themes which affect those companies. Luke is an archetypal investment geographer, and as it happens a former real geographer, the inspiration for my use of the term in this book.

Apart from time and rationality, another trade-off is between dealing frequency and dealing costs: the more an investor deals, the higher the costs – both commission and bid-offer spreads, and the indirect costs of more avoidable errors through dealing on weaker information. Luke spends several hours every day observing and thinking about markets, and yet he deals only a very few times a year. He focuses on quality of decisions, not quantity of decisions, believing that “one of the big mistakes in investing is to think that you’ve always got to be doing something”.

Geography

Luke is in his mid-50s and lives in a Suffolk coastal town, in a yellow detached house on a very wide and open street a few minutes from the sea. His childhood in South London was secure but not affluent: “there wasn’t much money, but nor was there any particular hardship”. He went to the local grammar school and then on to Exeter University in 1972 to study geography. After an MSc in transport planning, he spent the first six years of his career in this field in the South West, directly using both his academic degrees. He enjoyed his job, but in the early 1980s he gradually became aware of two structural problems which limited his long-term career prospects: his lack of a chartered engineering qualification, and the impact of Thatcherite cuts on local government.

In 1982, when he was 28, he resigned to spend two years doing an MSc in management, the forerunner of the MBA degree at the London Business School (LBS). “I gave up a reasonably secure job for two years of full-time education, with no guarantee of something better at the end of it. Many of my colleagues thought I was mad.”

He enjoyed the MSc course, despite the fact that it was “quite tough from a personal life perspective, and I was very uncertain what I would do at the end of it.” There was strong camaraderie amongst the students, with around a quarter who shared his motivation of escaping from poor pay and prospects in the engineering sector. He graduated in 1984, at the beginning of the boom leading up to the Big Bang reforms of the City in 1986, a period of strong demand for LBS graduates. After interviewing for fund management and analyst jobs he joined the small London office of an American bank, at a starting salary double what he had earned as a transport planner.

Into banking: a lucky break

Luke started his investment banking career in debt origination – identifying corporate clients who needed to raise money by issuing bonds to investors, and designing and marketing those bonds. After about 18 months, the American bank’s bond syndicate manager resigned, taking his number two with him, so Luke stepped up into the job – a lucky break which turbo-charged his early career.

Three years later he moved on to a large British bank. The new job shifted his market focus from debt origination in the eurobond market to the same function in the embryonic medium-term note market. A medium-term note is a flexible debt security with a term usually between five and ten years, and often with features such as put options or warrants which give embedded optionality. Initially this was a small market in London, but it grew rapidly in the 1990s, creating strong career opportunities. Medium-term notes will be unfamiliar to many readers, but the details are not important. The significant point is that operating in this market required a particularly broad worldview, which has also shaped Luke’s approach to personal investing.

“The medium-term note market is a global market, so you need a model of the whole world in your head. Over the years I did deals in 15 to 20 currencies – different financial environments, different legal and tax regimes, different cultures. And because the embedded optionality in the notes often related to the commodity or equity markets, I needed to keep abreast of those markets as well.”

This broad worldview helped with spotting opportunities for new issues which would appeal to both investors and issuers: “if say the Indonesian rupiah or Korean won were devalued, that might create an opportunity to do something based on Indonesian or Korean interest rates.” Luke’s long-standing habit of top-down thinking contrasts with the bottom-up surveyor investors in this book, who spent their formative investing years learning to analyse the accounts of individual companies, often giving little thought to the broader financial world.

The medium-term note market grew rapidly in the 1990s, creating strong career opportunities. Reflecting on this a decade after leaving banking, Luke noted the value of “picking the right train” in career decisions, a concept which has also informed his top-down investing. “By switching from local government into bond syndication, and from there into medium-term notes, I changed from a train going nowhere to a very fast train. In careers or in investment, it helps enormously to pick the right train – choose a field with long-term secular growth.”

The job was often intense: he routinely left home before dawn for most of the year to be at his desk between 7 and 8 in the morning, and stayed until 7 or 8 in the evening. In these years he did little personal investing, apart from unit trusts and other collective vehicles. “The compliance requirements as an investment bank employee made dealing in individual shares difficult, and anyway I never had the time.”

But he did make one big financial bet: in 1989, he sold his house west of London and moved to Suffolk, halving the size of his mortgage just before the property slump of the early 1990s. With 20 years’ hindsight, this may seem an obvious market call, but few people found it obvious enough to act decisively at the time. For Luke the decision was based partly on his macroeconomic perspective, and partly on his geographer’s sensibility: he foresaw trouble in the property market, and that the financial centre of London would probably drift eastwards towards Docklands. He repeated this type of call in 2006, downsizing to his present house as soon as his youngest child left home, partly because of his bearish macro view of the property market.

Leaving banking

By 1999, after nearly 15 years in investment banking, Luke had become weary of an intense job with a long daily commute from Suffolk and frequent international travel. Like many people in banking, he was wistful for a more relaxed lifestyle, but trapped by inertia and high financial rewards. The gilded cage was opened by dealing room ageism: “the bank had one of those periodic culls which indiscriminately target almost anyone over 45.”

Soon afterwards he joined a small treasury consultancy, which offered advice to non-financial companies on dealing with banks. He aimed to develop a new service, advising companies on raising money in the securities markets rather than bank loans: “I was a poacher turning gamekeeper, or vice versa, depending on how you look at it.” He persevered with this for about three years, but developing the business proved difficult. “The egos of the people to whom I was pitching often made it difficult for them to admit they needed help. And even if they knew it, their bosses didn’t expect to pay for help.”

In March 2000, Luke spent the whole month advising Marconi on its debt restructuring. After the month-end he realised that the movement in his personal share portfolio in March had been many times larger than his salary for that month, and indeed larger than the fee his firm had billed. “It made me reflect that perhaps I should be spending more time on investing, rather than earning.” His employer’s business suffered in the downturn after the September 2001 terrorist attacks, leading him to leave employment in early 2002. He was 47 years old. Apart from some sporadic ad hoc consultancy, he has been a full-time private investor since then.

The big picture: the neglected oil sector

When he began to spend more time on investment in the late 1990s, the habits of thought Luke had developed in his career made it natural to take a top-down perspective, scanning the whole investment landscape for value. In March 1999 this led him to focus on oil exploration and production companies. He had no particular expertise in the oil industry, and had never invested in the sector before, but thought that it offered clearly the best value in 1999. Although this may have seemed clear to Luke, it was a minority view at the time. On 4 March 1999 The Economist newspaper published its notorious “Drowning in oil” headline predicting a price of $5 per barrel of oil, almost to the day when Luke resolved to focus on the sector.

Luke made initial investments in a handful of what he thought were the best-value UK-listed oil explorers and producers. Over the next few years he increased these shareholdings, partly by investing consultancy earnings and partly by selling unit trusts and other collective vehicles in the technology sector in which he had invested during the 1990s. One of these oil stocks, Soco International, came to dominate his portfolio over the next decade.

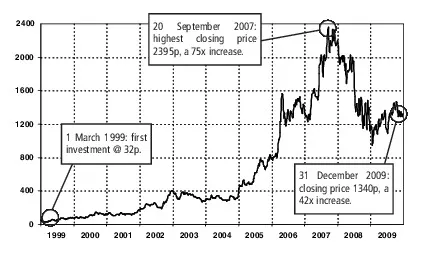

Soco International plc: a 42-bagger from March 1999 to December 2009

Source: data from ADVFN

From his earliest purchases in March 1999 at 32p the price rose 75 times at its peak in September 2007, and was still up 42 times at the end of 2009. Although he made only a small part of his total investment in Soco at 32p, this spectacular rise illustrates the potential of focusing on “quality of decisions, not quantity of decisions.” In almost every era of stock market history, there are a few shares like this, and if you can find them, buy them and sit tight, your life can be transformed. You only need to find one or two really good investment ideas to change your life.

Whilst Luke’s investment process always starts with top-down analysis, this is a beginning, not an end: he also learns a great deal about each of the handful of companies he holds. Oil exploration has a substantial learning curve: terms such as proven reserves, proven and probable (2P) reserves, possible reserves and so on all have precise technical meanings, and their nuances can be of critical importance in interpreting news announcements from oil companies.

He has always invested in a very few stocks, usually no more than six. “My view is that most of the benefit from diversification comes from the first few stocks.” Once he holds a stock, his ongoing research is focused on confirming that it retains “low downside and substantial upside.” Provided that it does, he is indifferent to short-term price movements: “I try to watch the business, not the share price.” Nor does he lose sleep over the possibility that some other stock might offer even higher returns over the next few weeks or months. “I think you are better off with a few good long-term choices, rather than flitting from one speculation to another, always chasing the latest hot stock in the market. Better to have a few good long-term friends, rather than change your friends every week for short-term advantage.”

I remarked that the volatility of oil exploration companies meant that their investment clientele overlaps with the technology sector – both attract uninformed small investors with excessive enthusiasm for particular companies. Did Luke agree? “Yes, dumb money is common in both sectors. But because of new discoveries of oil, exploration is one of the few sectors where it is possible – and not even all that rare – to have a large change in the fundamentals of a company overnight. In that respect I think it is different from most of the tech sector.” His bullish long-term view of the oil sector is predicated partly on the view that “oil and natural gas resources are limited, and ultimately we will see a buyer’s scramble by resource-short nations like China. I do not know when, but I am convinced it will happen.” His companies are picked partly for their plausibility as long-term targets of these strategic bidders.

Although his big picture approach has led to a portfolio weighted heavily in oils over much of the past decade, Luke also thinks deeply about other sectors; his many detailed bulletin board posts about the banking sector attest to this. But because he does no short selling, the banking part of his big pictu...