eBook - ePub

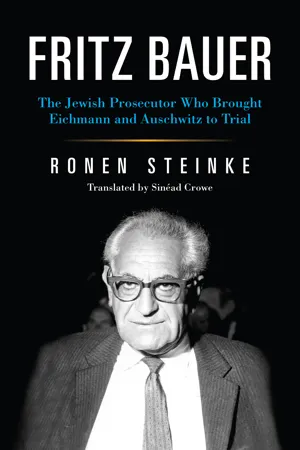

Fritz Bauer

The Jewish Prosecutor Who Brought Eichmann and Auschwitz to Trial

- 220 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Fritz Bauer

The Jewish Prosecutor Who Brought Eichmann and Auschwitz to Trial

About this book

A biography of the German Jewish judge and lawyer who survived the Holocaust, brought the Nazis to justice, and fought for the rights of homosexuals.

German Jewish judge and prosecutor Fritz Bauer (1903–1968) played a key role in the arrest of Adolf Eichmann and the initiation of the Frankfurt Auschwitz trials. Author Ronen Steinke tells this remarkable story while sensitively exploring the many contributions Bauer made to the postwar German justice system. As it sheds light on Bauer's Jewish identity and the role it played in these trials and his later career, Steinke's deft narrative contributes to the larger story of Jewishness in postwar Germany. Examining latent antisemitism during this period as well as Jewish responses to renewed German cultural identity and politics, Steinke also explores Bauer's personal and family life and private struggles, including his participation in debates against the criminalization of homosexuality—a fact that only came to light after his death in 1968. This new biography reveals how one individual's determination, religion, and dedication to the rule of law formed an important foundation for German post war society.

"What is clear—and what this book makes clear—is that without people like Fritz Bauer there would have been none of this prosecution of Nazi atrocities, no trials for Auschwitz camp guards or Adolf Eichmann, no rehabilitation of the German resistance against Hitler. Ronen Steinke deserves thanks for bringing this message of Fritz Bauer back to light in such an accessible form, balancing professional distance and sympathy." —Kai Ambos, Criminal Law Forum

"Illuminates the biography of a central actor in Germany's coming to terms with its Nazi past." —Jacob S. Eder, author of Holocaust Angst

German Jewish judge and prosecutor Fritz Bauer (1903–1968) played a key role in the arrest of Adolf Eichmann and the initiation of the Frankfurt Auschwitz trials. Author Ronen Steinke tells this remarkable story while sensitively exploring the many contributions Bauer made to the postwar German justice system. As it sheds light on Bauer's Jewish identity and the role it played in these trials and his later career, Steinke's deft narrative contributes to the larger story of Jewishness in postwar Germany. Examining latent antisemitism during this period as well as Jewish responses to renewed German cultural identity and politics, Steinke also explores Bauer's personal and family life and private struggles, including his participation in debates against the criminalization of homosexuality—a fact that only came to light after his death in 1968. This new biography reveals how one individual's determination, religion, and dedication to the rule of law formed an important foundation for German post war society.

"What is clear—and what this book makes clear—is that without people like Fritz Bauer there would have been none of this prosecution of Nazi atrocities, no trials for Auschwitz camp guards or Adolf Eichmann, no rehabilitation of the German resistance against Hitler. Ronen Steinke deserves thanks for bringing this message of Fritz Bauer back to light in such an accessible form, balancing professional distance and sympathy." —Kai Ambos, Criminal Law Forum

"Illuminates the biography of a central actor in Germany's coming to terms with its Nazi past." —Jacob S. Eder, author of Holocaust Angst

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Fritz Bauer by Ronen Steinke, Sinéad Crowe, Sinead Crowe,Sinéad Crowe in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Law & Law Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Publisher

Indiana University PressYear

2020Print ISBN

9780253046857, 9780253046857eBook ISBN

97802530468711

THE GERMAN WHO BROUGHT EICHMANN TO JUSTICE

His Secret

THE HEAVY OAK DOOR ON GERICHTSSTRASSE IN DOWNTOWN Frankfurt opened with barely a sound, and nobody noticed as twenty-seven-year-old Michael Maor slipped into the darkened building beyond. Maor knew exactly where to go, as they had meticulously mapped out his route for him beforehand. He made his way up the stone steps on the right until he reached the third floor, which stretched out ahead of him like a grand courtyard made of green linoleum. Moonlight streamed in through the windows. Maor’s attention was immediately drawn to a prominent white door flanked by marble columns, which, in the dark, looked pitch-black rather than their usual reddish-brown color. The door led to the office of Fritz Bauer, attorney general of the state of Hesse; you can’t miss it, they had told him.

The former Israeli paratrooper’s mission: to photograph the file he would find on the left-hand side of Bauer’s desk. The smell of cigars hung in the air, the long drapes were drawn, the walls were decorated with modern art, and, sure enough, on the left-hand side of the desk, Maor found a neat stack of papers. “The documents were emblazoned with SS insignia,” Maor later recalled, “and a photo of a man in uniform was stuck to the first page.”1

The file was that of Adolf Eichmann, the fiercely ambitious chief organizer of the Holocaust, the man who had planned the murder of millions of Jews down to the tiniest bureaucratic detail. On the evening of May 11, 1960—just a few weeks after Maor’s nocturnal operation—the Israeli secret service, Mossad, kidnapped Eichmann from his hideout in Buenos Aires. Mossad then sedated him, dressed him in an El Al airline uniform, and flew him first class on a passenger plane to Israel. The capture resulted in one of the most important trials of the twentieth century, a trial that would shape the development of the still nascent Israeli society. But the vital clue that triggered the chain of events leading to Eichmann’s capture had first appeared in a letter delivered in Frankfurt in 1957.2

The letter was from a German-born Jew named Lothar Hermann, who had been living in Argentina since fleeing the Nazis. Hermann wrote that Eichmann was living under an assumed name in a suburb of Buenos Aires. Hermann had discovered this by chance when it emerged that his own daughter had fallen in love with the mass murderer’s son. At the time, there was hardly anyone to whom the horrified father could turn. The Israeli government was tied up with its own urgent national security issues, the Americans had long since handed responsibility for prosecuting Nazi crimes over to the Germans, and the German judiciary was riddled with judges and prosecutors who had themselves been involved with the Nazi regime. The attorney general of Hesse was the only figure who appeared willing to take action—unilaterally, if necessary—in the hunt for Eichmann.

One reason why Bauer’s renown had spread as far as Argentina and Israel was that he was markedly different from most other high-profile German jurists. A Social Democrat of Jewish descent, he had managed to flee Germany in 1936, returning after the war to work in the judiciary, the branch of the German civil service where the old Nazi networks of power were most pervasive. Bauer’s work focused on bringing Nazi criminals to justice, and so it was to Bauer’s office that Lothar Hermann sent his revelation about Eichmann’s whereabouts.

The Israeli agent had just finished setting up his camera in Bauer’s office when he jolted to attention: “Suddenly I heard footsteps, and light came shining in under the door.” Hearing someone slowly shuffling across the green linoleum toward the office, Maor dived for cover behind Bauer’s desk. It sounded as if whoever was outside was dragging something across the floor.

Maor remained frozen in position until he realized it must be the cleaner. “She was obviously a bit lazy,” he said later, pointing out that she didn’t bother to clean the attorney general’s smoky sixty-square-meter office. The woman shuffled on past the office—“luckily for her,” Maor said ominously; failure was simply not an option for him that night. The light went out again.

It was no accident that the Eichmann file—the contents of which were passed straight on to Mossad—had been left open. Bauer himself had invited the nocturnal visitor, and so the operation was more of a clandestine handover of information than a break-in. Indeed, the operation was so covert that nobody—not even Bauer’s most trusted legal colleagues—knew anything about it.

Over the preceding years, Bauer had repeatedly seen his work thwarted by civil servants leaking sensitive information and warning Nazi suspects about their impending arrests. The police force had proven to be full of such leaks. Bauer’s small team of investigators avoided using police telex lines, as this would give several employees access to their messages. According to Joachim Kügler, a member of Bauer’s team, “Whenever I needed to send a telegram while I was working on the Auschwitz trial, I would go down to the market and ask a vegetable seller to send it.”3

Discretion was of paramount importance, as, in the 1950s and 1960s, warnings were being systematically leaked to Nazi criminals who had gone to ground. There was even a newsletter called Warndienst West (Western Warning Service) specifically devoted to issuing such alerts. Warndienst West was distributed by the Hamburg branch of the German Red Cross—itself run by a former SS Obersturmbannführer—to Wehrmacht and SS veterans’ associations in various countries. The source of the warnings was to be found right in the center of Bonn’s government district. Established in 1950 and led by a former prosecutor at a Nazi “special court” in Breslau, the Central Office for the Legal Protection of Nazi Suspects was based in the ministry of justice until 1953, after which it relocated to the foreign ministry.4 Once, when pursuing Reinhold Vorberg, the most active contributor to the Nazi regime’s policy of euthanizing people with disabilities, Bauer’s team filed a request with a court in Bonn for permission to launch secret investigations. The judge personally passed this confidential information on to a local lawyer, and Vorberg promptly fled to Spain.5

Former Nazi officials had regrouped to form more than just a few disparate networks; by the 1950s, they comprised a broad front running across state institutions. Thanks to the amnesty laws of 1949 and 1954, most Nazi criminals sentenced by German courts had already been pardoned. Moreover, both their sentences and the verdicts of the denazification courts had been stricken from their records. In the early days of the West German republic, the Allies and German democrats had hoped for a clean break, or at the very least a cleanup of state institutions. Since then, however, civil servant unions had successfully fought for the rights of almost all former Nazi officials to be reemployed. As a result, former Nazis were working in government ministries, holding positions up to the level of undersecretary. During the 1950s, virtually all former Nazi Party members were able to reassume positions within the West German judicial and administrative systems.

In July 1957, Paul Dickopf, a former SS Untersturmführer who now headed up the international division of the Bundeskriminalamt (the Federal Criminal Police Office), informed Bauer that the German police force would not be able to assist in the search for Eichmann. Dickopf claimed that as Eichmann’s offences had been political in nature, the Interpol charter prohibited the police from launching a manhunt.6 In 1958, thirty-three of the Bundeskriminalamt’s forty-seven senior officials were former members of the SS. When Bauer invited them to a meeting in 1960 to discuss investigations into suspected Auschwitz criminals, they sent a head of division who, as a former SS Sturmbannführer in Russia, had overseen the deportation of civilians to concentration camps.7 Erwin Schüle, the head of the newly established Central Office for the Investigation of National Socialist Crimes, commented in 1960 that West German police officials—many of whom were back in top positions—had been complicit “to an alarming degree” in Nazi crimes.8 The irony was not lost on anyone when it later emerged that Schüle had himself been a member of both the Nazi Party and the SA (Hitler’s storm troopers).

Even those Nazis hiding in far-off places like Buenos Aires were protected by vigilant, well-connected friends. This made the hunt for Eichmann exceptionally difficult. The German ambassador to Argentina, Werner Junker—who had once served as a diplomat under the Nazi regime—kept in close contact with right-wing exiles and personal acquaintances of Eichmann’s.9 Bauer was unaware that the Bundesnachrichtendienst, West Germany’s intelligence agency, had known about Eichmann’s address and assumed name in Argentina since 1952 but had chosen to keep this information to itself. “Carefully gather everything you can on Eichmann,” the agents had noted in a file that was only opened decades later.10 But while Bauer didn’t know that the Bundesnachrichtendienst had been suppressing information about Eichmann’s whereabouts, he nonetheless knew not to expect help from the intelligence service. The appointment of Reinhard Gehlen as its head made Bauer even more aware of the need to play his cards close to his chest. Gehlen had been responsible for Eastern espionage during the German war of extermination against the Soviet Union, and in his new position in postwar Germany, he continued to surround himself with his old cronies.

The story of how Bauer contributed to the arrest and prosecution of the world’s most famous living Nazi is thus the story of how he managed to beat all these odds. It is also the story of a series of lonely decisions Bauer was forced to make. In early November 1957, he met for the first time with the State of Israel’s representative in Germany, Felix Schinnar, to pass on his Eichmann tip-off. At the meeting, which took place at a secret location, Bauer told Schinnar that the only other person who knew about the clue pointing to Buenos Aires was the state premier of Hesse, Georg August Zinn, who was a friend of Bauer’s and a fellow member of the Social Democratic Party. Bauer stressed that no one else could be allowed to find out. Too much was at stake. Bauer intended to quietly circumvent the German institutions that had repeatedly perverted the course of justice.11

Shortly afterward, in January 1958, a Mossad agent working on Bauer’s information made an initial attempt to track down Eichmann in Buenos Aires. However, Eichmann’s alleged house at Calle Chacabuco 4261 turned out to be small and dilapidated. It didn’t remotely resemble the hideout of a powerful Nazi, and so the disappointed agent returned to Israel without investigating any further.12

Bauer wasn’t prepared to give up so easily, however. On January 21, 1958, he met for a second time with an Israeli contact, this time in Frankfurt, where he secured a promise that Mossad would track down Bauer’s informant, Lothar Hermann. Bauer even issued a fake ID document to enable the Israeli agent to pose as one of the attorney general’s officials.

But the second Mossad mission also ended in disappointment when it emerged that Hermann was almost blind and lived several hours away from Buenos Aires in the city of Coronel Suarez. It turned out that Hermann hadn’t lived in Buenos Aires for years. No longer willing to take Hermann at his word, Mossad was reluctant to make a third expedition to South America. The trail to Buenos Aires was about to go cold when Bauer noticed that some of his political adversaries seemed more agitated than usual.

On June 24, 1958, the German ambassador in Buenos Aires informed Bauer that all the embassy’s efforts to determine Eichmann’s whereabouts had reached a dead end. Paradoxically, however, he also insisted that Eichmann was unlikely to be hiding in Argentina and that in all probability he was in the Middle East. Shortly afterward, this odd message was echoed by another former Nazi, Paul Dickopf, the head of the Bundeskriminalamt’s international division. For the first time in his career, Bauer received a visit from Dickopf, who advised against searching for Eichmann in Argentina. There was no way that Eichmann was there, Dickopf insisted.13 This intervention only streng...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Foreword by Andreas Vosskuhle

- Acknowledgments

- 1. The German Who Brought Eichmann to Justice: His Secret

- 2. The Secret Jewish Life of Postwar Germany’s Most Controversial Jurist

- 3. The University Years (1921–1925): A Gifted Student

- 4. A Judge in the Weimar Republic: Bauer’s Attempts to Avert Catastrophe

- 5. Concentration Camp and Exile (1933–1949)

- 6. Rehabilitating the Plotters of July 20, 1944

- 7. “Murderers Among Us”: The Psychology of a Prosecutor

- 8. Bauer’s Greatest Achievement: The Auschwitz Trial (1963–1965)

- 9. The Fight for Gay Rights: Bauer’s Dilemma

- 10. Bauer’s Path to Isolation

- 11. 1968: The Body in the Bathtub

- Bibliography

- Index of Names

- About the Authors