![]()

1

Productivity: “it is almost everything”

Paul Krugman is one of the world’s best-known economists. He has a Nobel Prize in economics and a regular economics column. He once said, “productivity isn’t everything, but, in the long run, it is almost everything”. Few economists have not heard this quote. The reason productivity is so important, Krugman continued, is that “a country’s ability to improve its standard of living over time depends almost entirely on its ability to raise its output per worker” (Krugman 1994a: 11). This makes the idea of productivity look pretty important, and it is. But it has also been suggested that today the word most associated with productivity is puzzle. Productivity is a puzzle because it is a problem to understand conceptually; it is a problem to measure; it is a problem to explain and it is a problem to know how to improve it. Much of this book is about this productivity puzzle, but first we need to ask why productivity matters so much.

Imagine that we double the inputs we put into the economy. We might hope to double the output. But getting the same amount out as you put in is not very impressive. It is an example of what is called extensive growth. What we really want is more from the extra bits we put in. We want more output per hectare of land we use, more output per worker and more output per unit of capital. This is called intensive growth. Until the late nineteenth century, economists tended to talk of productiveness as a catch-all term. They were not very careful to distinguish between extensive growth and increasing what you get out per unit that is put in. But in the late nineteenth century they began to use the term productivity for this second effect. Productivity here is efficiency, it is a ratio of inputs to outputs and it is the driving force of intensive growth.

| Output | = | Productivity level | Changes in outputs | = | Productivity growth |

| Input | Changes in inputs |

We can get more out separately from each of the factors of production. There is the land input, and this might lead us to think of land productivity. There is labour: the physical and nervous energy we expend. This would lead us to think about labour productivity. And there is capital: the buildings, roads, machinery and computers that make our lives easier. This leads to the idea capital productivity. Productivity can also refer to getting more out from these factors of production when we combine them: this is what economists mean when they talk of total factor productivity.

After 1945 a focus on productivity became central to much of the debate about economic policy and economics. The Cold War seemed to involve a competition of two systems in which victory would go to the one with the superior productivity growth. “History is on our side. We will bury you”, said Nikita Khrushchev, the leader of the USSR, in 1956. He was wrong. Just over three and a half decades later the USSR collapsed. But geopolitical tensions have not gone away. China, with its own story of surging productivity growth, has emerged as a new challenger. In the poorer parts of the world, after decolonization, the hope too was to break free of the low-productivity–low-income traps that seemed to characterize the lives of the larger part of the world’s population. And in the most advanced regions, governments focused on productivity as one of the most important tests of longer-term economic success as well as one of the keys to shorter-run economic stability. Productivity came to be seen as important to political and social development and cohesion. If productivity growth could increase the size of the cake, there would be more for everyone. The edge would be taken off distributional conflicts.

Before the Second World War, economists had spent a lot of time thinking about distribution. Who gets what and why? The answers raised painful and significant theoretical problems. Economists are usually obsessed with the idea of diminishing returns: the first bit of chocolate you eat is a treat, but if you keep eating it then the pleasure diminishes and you may even become sick. This simple idea leads to an interesting position. An additional pound of income would seem to be more useful to a poor person than a rich one. Taking away a pound from a rich person to redistribute to a poor one looks like a sensible route to improving human welfare. For another Nobel Prize-winning economist, Robert Lucas, these ideas are steps too far. “Of the tendencies that are harmful to sound economics, the most seductive, and in my opinion the most poisonous, is to focus on questions of distribution”, he said in 2004. “The potential for improving the lives of poor people”, continued Lucas, “by finding different ways of distributing current production is nothing compared to the apparently limitless potential of increasing production” (Lucas 2004). If in the wider world a “politics of productivity” displaced a “politics of redistribution”, so in economics productivity analysis came to loom much larger than the analysis of distribution.

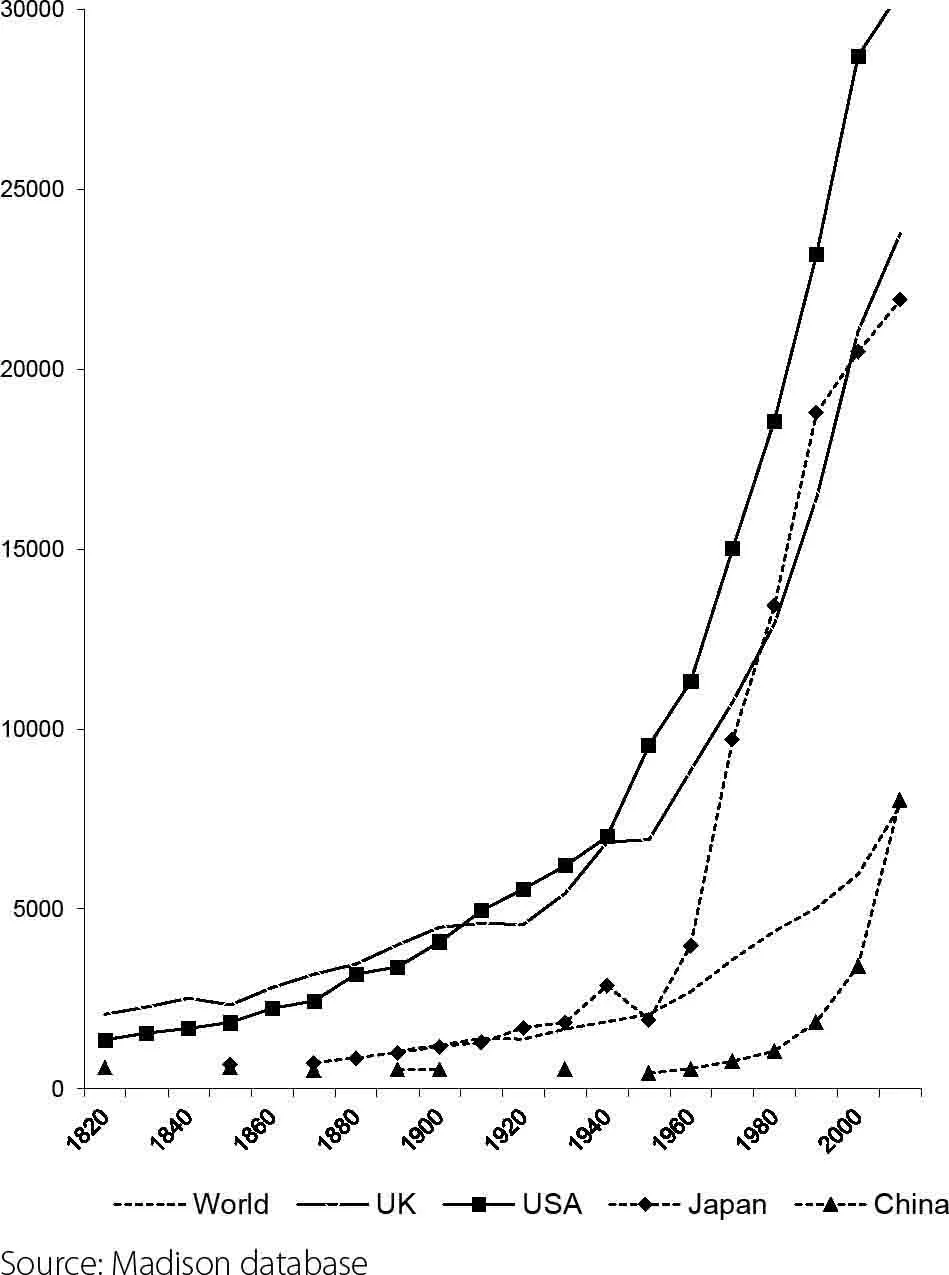

Let us accept this for the moment and look at the idea of “the apparently limitless potential of increasing production”. Figure 1.1 shows how output per head has changed globally, and for a number of countries, over nearly 200 years.

Figure 1.1 Per capita GDP for world and selected countries 1820–2010 in constant $1990

Output per head is not as close to a proper productivity measure as we would like. The input is total population – not labour or land and capital. But we do not have to go back too far for our estimates of the size of these inputs to become quite hazy. This figure of output per head will have to serve to illustrate the power of productivity growth. The phrase that is often used to explain how growth works is the “magic of compound interest”. Just as money in a bank account earns interest that can then be left there so the next year you get interest on both the original sum and the previous interest, so the same can apply in an economy. Productivity growth builds over time. The higher the rate of growth, the faster the increase in output per head. There is a simple trick that allows us to see this. If the rate of growth is 1 per cent then output per head will double every 70 years. If it is 2 per cent it will take 35 years and 3 per cent only 23.33 years, and so on. The doubling ratio is 70 divided by the rate of growth.

This is what has happened in the advanced world since the late eighteenth century, albeit unevenly. We can see this in the data in Figure 1.1 for the United Kingdom. For a long time, growth seemed restricted to Europe and especially the United States. But more recently some other economies have experienced even faster rates of sustained growth. You can see this in Figure 1.1 in terms of Japan and China. The first surge in output per head in Britain was linked to productivity growth bound up in the industrial revolution. But is the industrial revolution the whole cause of the change? Not quite. For the industrial revolution to work, for it to even be possible, there had to be what Rostow once called “preconditions” (Rostow 1960). These preconditions took a couple of centuries to emerge in western Europe. More radical accounts see the rise of capitalism as central to the development of these preconditions. They also argue that their development often involved major challenges to the old order: revolutions, civil wars and wars. Many mainstream accounts have tried to shut the door firmly against the idea of capitalism. But they then let it in again by the window when they say that to understand the variations in productivity levels and growth, “institutions matter”.

Before the advent of capitalism, and especially capitalism in its industrial form, change was painfully slow. People were born, lived and died in societies that seemed to move almost glacially. If the rate of growth was, say, 0.1 per cent, it would take 700 years to double output per head. This makes the creation of new conditions in western Europe from the sixteenth century onwards all the more special. This has also given rise to other major debates. One asks why Europe against, say, China? This is a debate both about when the so-called “great divergence” occurred and why. Relative levels of productivity play a key role in it. A second debate is then about where, when and why in Europe? Here too, arguments about productivity figure prominently. Since our discussion focuses on the modern era we can largely, but not completely, set aside these debates because some elements return when we look at how growth and productivity change has begun to come about in parts of the world that once seemed marginalized in the great divergence.

Figure 1.1 shows that surging growth has continued in some parts of the world. Look at the curves for Japan and then China. The growth in China also helps to explain an important part of the recent growth in global output per head. The bad news is that the gaps in productivity levels across the world are still huge (De Jong 2015). Table 1.1 gives some indicative examples of the gaps today using labour productivity. In this instance it is output – gross domestic product (GDP) – divided by workers rather than population. The measure is still crude but a better indicator than output per head. Because we have these data for a large number of countries, it is perhaps the most used comparative indicator.

Table 1.1 GDP per person employed in 2018 as percentage of US level

| USA | 100 | Japan | 63 | China | 27 |

| France | 74 | South Korea | 61 | India | 15 |

| Germany | 73 | Russian Fed. | 45 | Nigeria | 13 |

| UK | 70 | South Africa | 36 | Niger | 2 |

Source: US Conference Board.

Where productivity has grown the most, real wages have risen and the prices of goods fallen in relative terms, so that even those on average incomes enjoy standards of living once only available to monarchs and their richest supporters. The great economist Joseph Schumpeter, who we will encounter at a number of points, put this well, even if in the slightly misogynistic terms of his day,

Queen Elizabeth [the First] owned silk stockings. The capitalist achievement does not typically consist in providing more silk stockings for queens but in bringing them within the reach of factory girls in return for steadily decreasing amounts of effort.

(Schumpeter 1976 [1943]: 67)

To see the effect of this we only have to look at the amount of goods that we, in the advanced world, have and take for granted.

One type of productivity growth, more than any other, has made this possible. This is agricultural productivity. Agriculture once dominated human life because its productivity was so low. Peasants had to put almost all their effort into growing food. They got barely enough out to feed themselves, their lords and the small urban population. Yet in the last two centuries agricultural productivity has risen to such an extent that the word’s population has grown from 1 billion in 1800 to some 8 billion today. More impressive, we also eat better. If we do not it is not because there is not enough food but because some of the world’s population (ironically mostly in the countryside) lack the means to access it – the distribution issue again. Giovanni Federico has estimated that in the years 1800–70 the global food supply more or less expanded at the same rate as the population. This refuted the pessimism of Thomas Malthus who thought that population would always grow faster than the food supply. Then, in the decades 1870–1938, the global food supply may have increased at 0.15 per cent per head and, after 1945, at 0.56 per cent per head. Since 1945 it seems that agricultural productivity has grown everywhere, albeit to different degrees. What this has meant is that although the global population rose six to seven times between 1800 and 2000, the food supply increased around ten times (Federico 2005: 20).

We can see agricultural revolutions happening along with industrialization from the late eighteenth century in the advanced world. But Federico’s figures reflect the ways in which the really big global revolution has come about since 1945 in the poor world, and not least with new hybrid crops. Rising agricultural productivity means that fewer workers have been needed to produce the same or more. In 1800 some 80 per cent of the global labour force worked the land in one way or another. As late as 1950 it was still around two-thirds, but today it is down to some 30 per cent. The share has not only fallen relatively, but in the 2000s it even began to fall absolutely as productivity rose. The share, of course, varies enormously. In Africa, a farmer may today produce enough to feed several others. In Germany and the US, a farmer is said to supply 160 others (Handelsbatt Research Institute 2017: 10). Other forms of productivity growth will loom large in this book and perhaps seem more spectacular than the changes in agricultural productivity, but they are only possible because, when it comes to the food supply, we can now get so much more out from what we put in.

As agricultural productivity has grown, we have been able to move from working on the farm to working in urban factories and offices. In 1800 around 2 per cent of the world’s population lived in towns and cities. The figure was 8 per cent in 1900, 46 per cent in 2000 and over 50 per cent in 2019. Urban life has a host of problems – the world has been described as “a planet of slums” – but even for the poorest, the push of problems in the countryside is probably second to the pull of their “cities of dreams” (Davis 2006).

Life expectancy, too, has risen as productivity has grown. People have become healthier, grown...