![]()

PART I

THE DESCENT

OR ORIGIN OF MAN

![]()

CHAPTER I

THE EVIDENCE OF THE DESCENT

OF MAN FROM SOME LOWER FORM

Nature of the evidence bearing on the origin of man — Homologous structures in man and the lower animals — Miscellaneous points of correspondence — Development — Rudimentary structures, muscles, sense-organs, hair, bones, reproductive organs, &c. — The bearing of these three great classes of facts on the origin of man.

HE who wishes to decide whether man is the modified descendant of some pre-existing form, would probably first enquire whether man varies, however slightly, in bodily structure and in mental faculties; and if so, whether the variations are transmitted to his offspring in accordance with the laws which prevail with the lower animals; such as that of the transmission of characters to the same age or sex. Again, are the variations the result, as far as our ignorance permits us to judge, of the same general causes, and are they governed by the same general laws, as in the case of other organisms; for instance by correlation, the inherited effects of use and disuse, &c.? Is man subject to similar malconformations, the result of arrested development, of reduplication of parts, &c., and does he display in any of his anomalies reversion to some former and ancient type of structure? It might also naturally be enquired whether man, like so many other animals, has given rise to varieties and sub-races, differing but slightly from each other, or to races differing so much that they must be classed as doubtful species? How are such races distributed over the world; and how, when crossed, do they react on each other, both in the first and succeeding generations? And so with many other points.

The enquirer would next come to the important point, whether man tends to increase at so rapid a rate, as to lead to occasional severe struggles for existence, and consequently to beneficial variations, whether in body or mind, being preserved, and injurious ones eliminated. Do the races or species of men, whichever term may be applied, encroach on and replace each other, so that some finally become extinct? We shall see that all these questions, as indeed is obvious in respect to most of them, must be answered in the affirmative, in the same manner as with the lower animals. But the several considerations just referred to may be conveniently deferred for a time; and we will first see how far the bodily structure of man shows traces, more or less plain, of his descent from some lower form. In the two succeeding chapters the mental powers of man, in comparison with those of the lower animals, will be considered.

The Bodily Structure of Man.—It is notorious that man is constructed on the same general type or model with other mammals. All the bones in his skeleton can be compared with corresponding bones in a monkey, bat, or seal. So it is with his muscles, nerves, blood-vessels and internal viscera. The brain, the most important of all the organs, follows the same law, as shewn by Huxley and other anatomists. Bischoff,[1] who is a hostile witness, admits that every chief fissure and fold in the brain of man has its analogy in that of the orang; but he adds that at no period of development do their brains perfectly agree; nor could this be expected, for otherwise their mental powers would have been the same. Vulpian[2] remarks: "Les différences réelles qui existent entre I'encéphale de l'homme et celui des singes supé rieurs, sont bien minimes. Il ne faut pas se faire d'illusions à cet égard. L'homme est bien plus prés des singes anthropomorphes par les caractéres anatomiques de son cerveau que ceux-ci ne le sont non-seulement des autres mammiféres, mais mêmes de certains quadrumanes, des guenons et des macaques."

But it would be superfluous here to give further details on the correspondence between man and the higher mammals in the structure of the brain and all other parts of the body.

It may, however, be worth while to specify a few points, not directly or obviously connected with structure, by which this correspondence or relationship is well shewn.

Man is liable to receive from the lower animals, and to communicate to them, certain diseases as hydrophobia, variola, the glanders, &c.; and this fact proves the close similarity of their tissues and blood, both in minute structure and composition, far more plainly than does their comparison under the best microscope, or by the aid of the best chemical analysis. Monkeys are liable to many of the same non-contagious diseases as we are; thus Rengger,[3] who carefully observed for a long time the Cebus Azaræ in its native land, found it liable to catarrh, with the usual symptoms, and which when often recurrent led to consumption. These monkeys suffered also from apoplexy, inflammation of the bowels, and cataract in the eye. The younger ones when shedding their milk-teeth often died from fever. Medicines produced the same effect on them as on us. Many kinds of monkeys have a strong taste for tea, coffee, and spirituous liquors: they will also, as I have myself seen, smoke tobacco with pleasure. Brehm asserts that the natives of north-eastern Africa catch the wild baboons by exposing vessels with strong beer, by which they are made drunk. He has seen some of these animals, which he kept in confinement, in this state; and he gives a laughable account of their behaviour and strange grimaces. On the following morning they were very cross and dismal; they held their aching heads with both hands and wore a most pitiable expression: when beer or wine was offered them, they turned away with disgust, but relished the juice of lemons.[4] An American monkey, an Ateles, after getting drunk on brandy, would never touch it again, and thus was wiser than many men. These trifling facts prove how similar the nerves of taste must be in monkeys and man, and how similarly their whole nervous system is affected.

Man is infested with internal parasites, sometimes causing fatal effects, and is plagued by external parasites, all of which belong to the same genera or families with those infesting other mammals. Man is subject like other mammals, birds, and even insects, to that mysterious law, which causes certain normal processes, such as gestation, as well as the maturation and duration of various diseases, to follow lunar periods.[5] His wounds are repaired by the same process of healing; and the stumps left after the amputation of his limbs occasionally possess, especially during an early embryonic period, some power of regeneration, as in the lowest animals.[6] The whole process of that most important function, the reproduction of the species, is strikingly the same in all mammals, from the first act of courtship by the male[7] to the birth and nurturing of the young. Monkeys are born in almost as helpless a condition as our own infants; and in certain genera the young differ fully as much in appearance from the adults, as do our children from their full-grown parents.[8] It has been urged by some writers as an important distinction, that with man the young arrive at maturity at a much later age than with any other animal: but if we look to the races of mankind which inhabit tropical countries the difference is not great, for the orang is believed not to be adult till the age of from ten to fifteen years.[9] Man differs from woman in size, bodily strength, hairyness, &c., as well as in mind, in the same manner as do the two sexes of many mammals. It is, in short, scarcely possible to exaggerate the close correspondence in general structure, in the minute structure of the tissues, in chemical composition and in constitution, between man and the higher animals, especially the anthropomorphous apes.

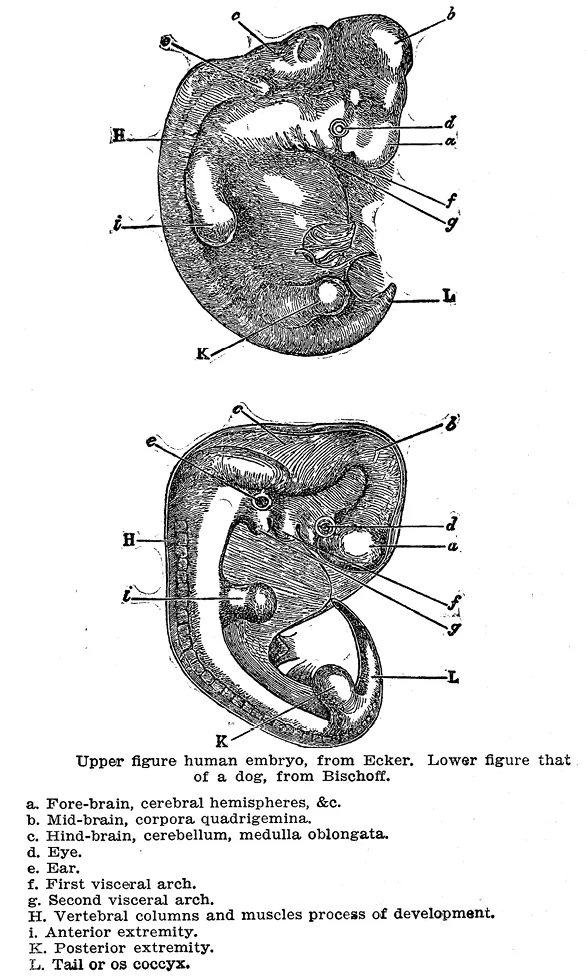

Embryonic Development.—Man is developed from an ovule, about the 125th of an inch in diameter, which differs in no respect from the ovules of other animals. The embryo itself at a very early period can hardly be distinguished from that of other members of the vertebrate kingdom. At this period the arteries run in arch-like branches, as if to carry the blood to branchiæ which are not present in the higher vertebrata, though the slits on the sides of the neck still remain (f, g, fig. 1), marking their former position. At a somewhat later period, when the extremities are developed, "the feet of lizards and mammals," as the illustrious Von Baer remarks, "the wings and feet of birds, no less than the hands and feet of man, all arise from the same fundamental form." It is, says Prof. Huxley,[10] "quite in the later stages of development that the young human being presents marked differences from the young ape, while the latter departs as much from the dog in its developments, as the man does. Startling as this last assertion may appear to be, it is demonstrably true."

As some of my readers may never have seen a drawing of an embryo, I have given one of man and another of a dog, at about the same early stage of development, carefully copied from two works of undoubted accuracy.[11]

After the foregoing statements made by such high authorities, it would be superfluous on my part to give a number of borrowed details, shewing that the embryo of man closely resembles that of other mammals. It may, however, be added that the human embryo like-wise resembles in various points of structure certain low forms when adult. For instance, the heart at first exists as a simple pulsating vessel; the excreta are voided through a cloacal passage; and the os coccyx projects like a true tail, "extending considerably beyond the rudimentary legs."[12] In the embryos of all air-breathing vertebrates, certain glands called the corpora Wolffiana, correspond with and act like the kidneys of mature fishes.[13]

Fig. 1.

Even at a later embryonic period, some striking resemblances between man and the lower animals may be observed. Bischoff says that the convolutions of the brain in a human fœtus at the end of the seventh month reach about the same stage of development as in a baboon when adult.[14] The great toe, as Prof. Owen remarks,[15] "which forms the fulcrum when standing or walking, is perhaps the most characteristic "peculiarity in the human structure;" but in an embryo, about an inch in length, Prof. Wyman[16] found "that the great toe was shorter than the others, and, instead of being parallel to them, projected at an angle from the side of the foot, thus corresponding with the permanent condition of this part in the quadrumana." I will conclude with a quotation from Huxley,[17] who after asking, does man originate in a different way from a dog, bird, frog or fish? says, "the reply is not doubtful for a moment; without question, the mode of origin and the early stages of the development of man are identical with those of the animals immediately below him in the scale: without a doubt in these respects, he is far nearer to apes, than the apes are to the dog."

Rudiments.—This subject, though not intrinsically more important than the two last, will for several reasons be here treated with more fullness.[18] Not one of the higher animals can be named which does not bear some part in a rudimentary condition; and man forms no exception to the rule. Rudimentary organs must be distinguished from t...