![]()

Chapter One

ATLANTIC PURGATORY

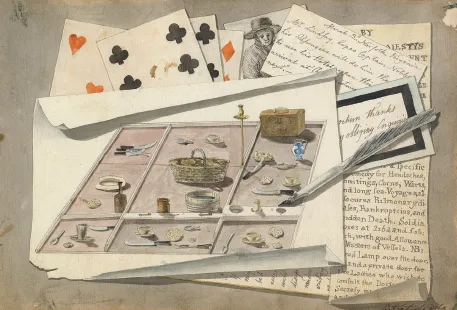

TWO WATERCOLORS capture Latrobe’s reflections on the eve of his arrival in Norfolk, Virginia, concluding a painful and protracted Atlantic crossing. On March 3, 1796, he completed First View of the Coast of Virginia, henceforth First View of Virginia [FIG. 1.1], and on the following day, Breakfast Equipage set out for the Passengers of the Eliza, the Captain and Mate in all 9 Persons, March 4th, 1796 being the compleat set, henceforth Breakfast Equipage [FIG. 1.2].

Sea and sky dominate First View of Virginia. Small, regular waves rhythmically lick the foreground. Two sailing vessels—a diminutive scouting dingy and a meticulously rendered transoceanic vessel—bookend the view. A thin ribbon of woodlands defines the horizon, but is almost lost between watercolor washes of sea and clouds.1 The view anticipates arrival, but conveys an air of stillness, rather than excitement, explained by Latrobe’s recollection that, “the wind died away and it became perfectly calm” as soon as land was spotted.2

The following day, while still idling, Latrobe completed Breakfast Equipage. In contrast to First View of Virginia, Breakfast Equipage is claustrophobic. A trompe l’oeil, it layers a stack of letters, notes, playing cards, and a freshly finished watercolor sketch. Rather than signaling journey’s end, it traps its viewer, ensnaring the eye within a confusing array that seems to chafe at unending travel. In their contrasting genres and perspectives, First View of Virginia and Breakfast Equipage set the stage for understanding the breadth and significance of Latrobe’s watercolor practice during and after his transatlantic voyage.

From departure to landing, Latrobe documented his voyage in a sketchbook and journal. He used images and notations to record events, as well as sites encountered, and flora, fauna, and scientific phenomena observed. From among this array, this chapter focuses on works in which Latrobe gives visual form to the experience of immigration. These images would be significant if analyzed merely as evidence of an immigrant’s journey, but they are even more so due to the meta-narratives Latrobe constructed across them, using ancient literature and history as resources to construct a reflective heroic and narrative assessment of his life. Here, Latrobe’s Atlantic sketchbook is considered as the first effort in carefully crafted self-fashioning through art and text, a process that Latrobe continued throughout his immigrant period. Across these images, a distraught man staged himself as epic hero, through a self-fashioned vision that brought perspective to the jarring experiences of immigration.

The epic landscapes of Latrobe’s Atlantic crossing offer an opportunity to establish the foundations of the artistic, textual, and philosophical practices that recur throughout this book. In this discrete body of images, Latrobe explored self, site, and form in ways that he reemployed effectively when traveling throughout Virginia. As a mature artist and thinker, he drew on the rich resources of his previous education and experiences to construct a perspective toward travel and personal transition. The diverse nature of Latrobe’s education in watercolor is the subject of Chapter 2, and the significant stakes of the analysis in that chapter can be better understood after studying Latrobe’s Atlantic watercolors. Although these watercolors look toward Virginia, they also offer us the most complete taste available of Latrobe as a European artist prior to his immersion in the Virginian landscape. In these works, Latrobe is an emigrant artist, looking forward to an uncertain new phase of life in the United States.

AN EPIC PERSPECTIVE

Latrobe built up epic associations to his travels from the first page of his Atlantic sketchbook. He boarded the Eliza, an American ship, on November 25, 1795, landing in Virginia some four months later.3 Latrobe recorded his departure on the title page and wrote, in Latin: “forsan et haec olim meminisse iuvabit” (“perhaps someday it will be pleasing to remember even these things”).4 As a personal notation, the phrase defines the sketchbook as a place of memory, commemorating current miseries and anticipating a brighter future. This well-known line from Vergil’s Aeneid also sets an intellectual and philosophical tone.

Latrobe’s citation makes sense. It resonates with the unhappiness of his life. Though only thirty-one years old, he sailed with a heavy heart, in extended mourning over his wife Lydia and his mother, who died in rapid succession.5 Later, Latrobe would assert that his immigration was driven by grief, writing: “The loss of my wife made business irksome to me, and I therefore resolved to leave a country where everything reminded me how happy I had been and how miserable I was.”6 After his departure, Latrobe’s sadness surely deepened as he worried over the two young children he left behind. His emotional distress was compounded by financial disaster, and his hasty departure was timed to escape bankruptcy proceedings.7 It is uncertain whether Latrobe intended a permanent relocation, but he doubtless anticipated a prolonged absence due to his finances. He set sail amid heartbreak, social ruin, and professional disappointment. Latrobe’s Aeneid reference proved apt for his Atlantic crossing. He endured a miserable voyage—suffering seasickness, life-threatening storms, and unlikeable companions—all of which he painstakingly documented. In such a context, Vergil’s words could have encouraged Latrobe and put his difficulties into perspective.

Latrobe had a thorough Classical education and his understanding of the Aeneid citation would surely have considered its specific literary context. Book I finds Aeneas, the great Trojan hero, wandering the Mediterranean with his loyal troops, seeking a safe harbor. Their ill-fated journey, chronicled throughout the Aeneid, had been set into motion by the destruction of Troy and the preceding decade of war. Aeneas suffers the loss not just of his city, but also of his dear wife Creusa, who died fleeing Troy. The Aeneid begins in medias res, introducing a hero and his companions worn down by disasters. Devastated by losses and never-ending troubles, they begin to abandon hope. As their leader, Aeneas needs to raise their spirits, a task performed in the speech from which Latrobe drew, here captured in the verse translation of John Dryden’s that was popular in Latrobe’s lifetime:

Endure and conquer! Jove will soon dispose

To future good our past and present woes.

With me, the rocks of Scylla you have tried;

Th’ inhuman Cyclops and his den defied.

What greater ills hereafter can you bear?

Resume your courage and dismiss your care,

An hour will come, with pleasure to relate

Your sorrows past, as benefits of Fate.

Thro’ Various hazards and events, we move

To Latium and the realms foredoom’d by Jove.

Call’d to the seat (the promise of the skyes)

Where Trojan kingdoms once again may rise,

Endure the hardships of your present state;

Live, and reserve yourselves for better fate8

The full speech promises a better future as a reward for great suffering. Aeneas characterizes the harsh turns of fate as driving toward a new life in “Latium,” prefiguring the dawn of a new Trojan civilization on the Italian Peninsula, where he was fated to become the founder of Rome. Elsewhere, Latrobe complains, “My destiny is not blind. She has a keen active eye to discover thorny paths for me to walk in.”9 Reflecting on Aeneas’s words could allow Latrobe to toy with his own life fantasies. Traveling from Britain to the United States, he looked toward a New World Promised Land, where his troubles could remain in his past and a brighter future could unfold.

However, Vergil also shares the secret of Aeneas’s words with the reader: the speech is an elaborate ruse designed to cheer his followers, but one in which Aeneas has no faith. It is a performed deception; the rhetorical cognate of a trompe l’oeil. Aeneas has received omens promising the rosy future he invokes, but he does not believe them. His public face shows hope, but privately his heart and spirit are broken. Anecdotes from Latrobe’s Atlantic voyage testify that he would have understood Aeneas’s conflicted experience, since Latrobe too experienced disjuncture between the public persona he maintained and his inner personal struggles. When interacting with his shipmates, Latrobe behaved like a high-class intellectual (doing such things as awarding his pianoforte his paid berth in the first-class cabin and flaunting his British status vis-a-vis his uncouth American shipmates), but these public performances of status masked inner anxieties.10

General affinities in emotion and ill-starred fate may have drawn Latrobe to Aeneas’s words, but the larger cultural milieu of the Age of Revolutions could also have made their contexts seem similar. Vergil lived at the end of the Roman Republic and witnessed the ascent of Octavian as the first Roman emperor Augustus.11 Vergil’s era, with its accompanying political, social, and personal anxieties can be understood as having some similarities to the restive Age of Revolutions. Richard F. Thomas has observed, “Virgil’s poetry is constantly and unrelievedly grappling with the problems of existence in a troubled and violent world.”12 The currents of Vergil’s tumultuous historical context run palpably throughout the Aeneid, making it exceptionally relevant to an individual caught up in the throes of international political anxiety. Both Vergil and Aeneas lived in worlds wherein “the ocean is moved to the very depth,” circumstances that may have invited Latrobe to closely associate himself with the epic.

Latrobe’s citation of Vergil would also have functioned within the broader neoclassical climate of Britain in which he was immersed. He espoused a neoclassical approach that integrated thoughtful use of ancient inspiration combined with sensitive consideration of modern purposes. This approach developed with an awareness that classicism could be employed in society for political purposes. Elite men often honed their public personae by employing civic concepts, such as liberty and republicanism, which were rooted in, and interpreted via, the ancient world. These cultural building blocks transcended individual assessments of ancient personae or historical events and formed the driving cultural force of the sociopolitical sphere. As Philip Ayres asserts: “for purposes of political self-justification the classical political heritage served too conveniently to be ignored . . . very few would have denied the continuing validity of the classical ideal of libertas or the social virtue obligatory in citizenship of civitas.”13When a figure of Latrobe’s stature employed Classical references, even within private texts or images, he did so both for the precise ways that they related to the life stories of a particular ancient figure and also for their political resonance.

Within this cultural backdrop, Latrobe’s citation from the Aeneid has a more grandiose allusion. In his speech, Aeneas refers to the future founding of Rome, a land of peaceful prosperity. The connection of peace and prosperity with Rome was a well-known aspect of the political platform of Augustus.14 Much debate existed in the late eighteenth century about where Britain stood within the cycle of its own imperial history. The American Revolution damaged British claims to a culture of libertas, as colonists accused their motherland of various oppressions.15 These anxieties were furthered by the French Revolution, jostling the stable imprimatur of Europe’s reigning kings. While aboard the Eliza, Latrobe read Edward Gibbon’s History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire and likely meditated on the current circumstances of Britain and the United States via this historical account.16 In such a context, the United States could, indeed, be seen to offer the prospect of a new Golden Age. If in the Aeneid the hero travels toward his forecast role as founder of a new, prosperous civilization, then Latrobe could extend this frame to think of his own future. Was he, as an artist whose craft could be compared to that of Vergil, headed toward a prosperous New World Latium? If so, what would his role be there? Many of Latrobe’s watercolors and writings of his immigrant years skirt around these issues, pondering possibilities both for his own future and for the young nation.

One final point is worth consideration in assessing Latrobe’s meditations on the Aeneid alongside dreams of h...