![]()

Coriolanus is a Roman history play and Shakespeare’s last tragedy. It is a natural choice in times of political turbulence. The play focuses on the political divide between democracy, as favoured by the tribunes, and the autocracy represented by Coriolanus. He can be seen either as a hero deserted by a fickle populace, or as a villain whose arrogance threatens dictatorship. In 1930s Paris it was suppressed as the cause of pro- and anti-Fascist street demonstrations. The Nazis identified Coriolanus with Hitler as a model of leadership. Conversely, Brecht’s adaptation of the play presented it as a tragedy for the proletariat. And a production in Communist Moscow stressed Coriolanus’s treachery and aristocratic pride. It was hailed as a lesson in the betrayal of the people by an individualistic leader in the Western mode.

Shakespeare introduced a human dimension, in Coriolanus’s dependence upon his mother Volumnia. She prides herself on having moulded her son, and his identity relies to a pathological degree on her esteem. The tone of the play is serious throughout, without any of the comic characters, low-life scenes, or other devices that Shakespeare often used to leaven his tragedies. What little comedy there is resides in Coriolanus’s unbending attitude, the tribunes’ wily manipulations, and the cowardice, hypocrisy and fickleness of the plebeians.

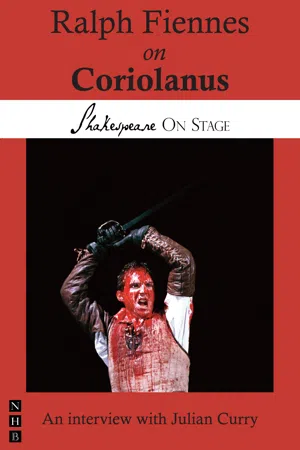

When I asked Ralph Fiennes if he was willing to be interviewed for this book, he was adamant that this was the role he wanted to talk about. Despite his brilliance on the battlefield, Coriolanus is amongst the least sympathetic of Shakespeare’s tragic figures. He is haughty and anti-democratic, sneers at hungry plebeians and is completely devoid of political tact. This is part of the character’s fascination. I’d worked with Ralph years earlier when he was playing the saintly, unworldly Henry VI at the RSC. But he is not an actor who needs to be taken to the audience’s heart. He put down a strong marker to that effect as the sadistically amoral Amon Goeth in Schindler’s List, and has since notched up several other very nasty pieces of work. When I went to meet him, one morning in July 2007, I thought there must have been a mistake about the address. The East London street was narrow and dingy, a knock at the door produced no response. Not a predictable film star’s residence. However, I phoned up and Ralph answered, having just got out of the bath. He let me into a pleasant, relaxed dwelling – open plan with bare brick walls – and made tea and toast. He proceeded to speak about the character with tremendous enthusiasm and urgency. I had to suggest a break in recording or I thought he would never get round to eating the toast.

![]()

Julian Curry: You’ve played plenty of the great Shakespearean parts. What’s special about Coriolanus?

Ralph Fiennes: It’s an odd role for me. I did it paired with Richard II, always a part I’d had my eye on. Jonathan Kent suggested a double bill with Coriolanus. There’s no particular connection between the plays, except they’re both about people who aspire to power and abuse it. They can’t handle it, and fuck it up. And I just became obsessed with this man. He’s one of the hardest characters to like, I think. The play is like a horrendous, uncompromising cliff face. It doesn’t have any of the warm, human, lyrical moments that you associate with Shakespeare. It seems to be a relentlessly uncompromising, jagged piece. Likewise, he is this peculiar, twisted, repressed machine. He’s pulped and conditioned, malformed by his mother. But I love the anger in it. And he has this aspiration to unbending purity. It can be repellent and fascist, but it’s also… he’s trying to be something distilled. I think it is a real tragedy. And interestingly, most people I spoke to seemed to dislike him initially, and then feel he is the victim of political manipulation and Machiavellian intrigue. Which he is – he’s manipulated by the tribunes, by the people.

And by Aufidius later on.

Yes. Well, he’s betrayed by Aufidius.

You’ve worked with Jonathan Kent a lot, so presumably that gives you a useful kind of shorthand. Can you describe his processes?

He comes with a strong design concept, look – whatever you want to call it – that’s well thought out. But I don’t think the cast ever felt pushed into anything. Maybe with Richard II (which Jonathan had been in before, as an actor) there was more sense of that. I remember thinking sometimes, ‘Why should I do that?’ But with Coriolanus I felt free. It evolved between us. He’s very open to see what happens. The best thing for me, the way I love, is when you both have ideas. The director and the actor each has an idea, a sketch in their heads.

Two-way traffic.

Yeah. You can put things on the table. You’re not sure about this, but that was good, and what happens if you do such-and-such. The setting was very strong, because the two plays were designed to be in the Gainsborough Studios, the old Hitchcock film studios in Shoreditch which have since then, tragically, been turned into modern-style apartments. But because the developer was about to knock them down, we could mess with the structure relatively cheaply. We had in essence what was originally built, a Victorian or Edwardian power station. There had been a thick, heavy, concrete floor across the middle that ...