![]()

As You Like It divides critics. ‘A work of great literary value,’ say some. ‘Lacking artistry, a mere crowd-pleaser,’ say others. Nonetheless, it remains very popular. On the surface the play is a simple pastoral romantic comedy with little of the darkness of Shakespeare’s other mature comedies, and a happy ending is never in doubt. But at a deeper level it touches on a host of subjects such as love, nature, ageing and death. The comedy’s genius lies not in its paper-thin plot but in its characters. Jaques prides himself on his abilty to ‘suck melancholy out of a song as a weasel sucks eggs’ [2.5]. His sardonic commentary and Touchstone’s restless bawdy innuendo are balanced against Rosalind, whose generosity of spirit, complexity of emotion and subtlety of thought make her one of Shakespeare’s most fully realised and beguiling characters. Rosalind blends front-foot energy with vulnerability; she dominates all around her, then proceeds to faint at the sight of Orlando’s blood.

Gender reversal is central to the play. Rosalind disguises herself as the boy ‘Ganymede’, whose name, taken from one of Jove’s lovers, carries homoerotic overtones. Orlando enjoys acting out his romance with Ganymede, almost as if the beautiful boy who looks strangely like the woman he loves is even more appealing than the woman herself. As You Like It lampoons the conventions of courtly love. Characters lament their sufferings in love, but their anguish is skin deep. ‘I to live and die her slave,’ writes Orlando, but his verses are mocked by Rosalind as a ‘tedious homily of love’ [3.2]. She asserts that ‘men have died from time to time, and worms have eaten them, but not for love’. But whereas Touchstone and Jaques merely focus on romantic folly, Rosalind champions love so long as it is grounded in the real world. She knows that ‘Men are April when they woo, December when they wed’ [4.1].

My own experience of acting in As You Like It is limited to a cough-and-a-spit at Stratford in 1968, when a weird thing happened. (Old Actor’s Anecdote coming up…) One midweek matinee I’m one of a bunch of lads making up the numbers onstage, listening to the First Forest Lord describe the death of a stag. It’s late in the season and advanced boredom has set in; we’ve heard this stuff many times before. ‘Must be about 2.45,’ I think to myself. ‘If I was to nip across the road to The Duck I could get in a quick pint before closing time… Hmmm, tempting… Yes, to hell with it, that’s what I’ll do right now!’ I’m about to sneak off the stage and over to the pub, when I realise that I am the actor I’m listening to. I am playing the First Forest Lord. I’ve become disembodied, and am listening to myself delivering the stag’s death speech on autopilot.

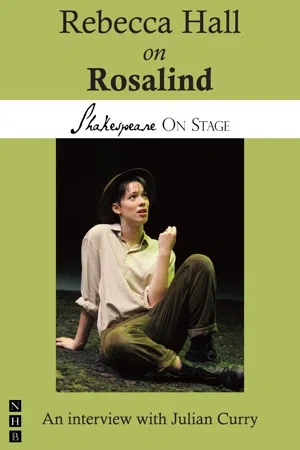

Rebecca Hall was twenty-seven when we met, by some years the youngest contributor to this book. She was already well on the way to a highly successful career, having started six years earlier with an award-winning debut in Shaw’s Mrs Warren’s Profession. She had arrived with a bang. Her Rosalind followed immediately afterwards, and created waves on both sides of the Atlantic. It was easy to understand why she had dropped out of Cambridge in mid-degree, from sheer impatience to get cracking as an actress. I interviewed her in the summer of 2009 at the matchbox flat in central London where she was staying, during her run at the Old Vic Theatre playing Hermione in The Winter’s Tale and Varya in The Cherry Orchard for Sam Mendes’ Bridge Project.

![]()

Julian Curry: You played Rosalind in Bath in 2003. And soon afterwards in New York and California. And you’d have been – what?

Rebecca Hall: Twenty-one, just. I turned twenty-one the day before we started rehearsals.

An excellent age to play Rosalind.

Yeah, it felt like a good age.

It was your professional debut in Shakespeare?

Yes, it was. Before that I’d just done Shaw’s Mrs Warren’s Profession and The Fight for Barbara, which is a very rarely performed D.H. Lawrence play. So it was my third professional production.

The director was not a debutant though, was he?

No, not at all. Long-standing.

He was your dad, Sir Peter Hall.

Yeah.

How was it, being directed by him?

Well, we’d figured out how to work together by that point, in Mrs Warren’s Profession, which he also directed. That was much more about how we’d collaborate, would it be okay, or would it ruin my career chances? By the time we got to As You Like It those things had stopped being a concern because we’d already established a strong working relationship, with a sort of ease. He started talking about As You Like It towards the end of Mrs Warren’s Profession, saying I should do it. He was quite passionate about it, because he’d never done the play before. Ever since he knew I wanted to be an actor, and thought I was talented, he was always making noises about it, saying ‘You’d be a really good Rosalind, you must do it one day.’

Can you remember why he thought you’d be a good Rosalind?

Probably because I’m ‘more than common tall’ [1.3]!

There were lots of wonderful things written about your performance, but it doesn’t sound like the sunniest Rosalind. ‘Downcast’ was a word used.

I don’t know whether she was downcast…

Somebody else said ‘… brings out a profound sadness in the character as if her inability to declare her love was a source of spiritual frustration.’

Yes, I think that’s probably accurate. It was clear to me from the first reading that this is not someone who is easy with love. I don’t think anyone really is, and that’s ultimately what Shakespeare’s doing. He’s writing a play about many different aspects of love. Falling in love is a dangerous business, with all sorts of possibilities of rejection. The backdrop to Rosalind’s story is that she’s brought up in a horrible court with her evil uncle, her father’s been banished, she’s alienated, she’s got no parental guidance. I think she’s very fragile and vulnerable, and desperately wants to love, is open to it. For people with those defence mechanisms and problems, I think when they do fall in love it can be all the more beautiful and joyful because of the hardship that comes with it.

Did you know the play well beforehand?

No. I’d never seen it, and I didn’t know it. I didn’t study it at Cambridge for some reason, and I didn’t study it at school, therefore I was completely fresh to it.

So you had no preconceptions.

No...