- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

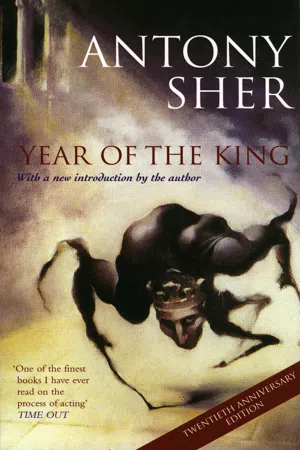

Year of the King

About this book

A classic of theatre writing, a unique insight into the creation of a landmark Shakespearian performance.

Antony Sher's stunning performance for the Royal Shakespeare Company as Richard III on crutches – the so-called 'bottled spider' – won him both the Laurence Olivier and Evening Standard Awards for Best Actor. This book records – in the actor's own words and drawings – the making of this historic theatrical event.

This edition of Year of the King is published on the twentieth anniversary of the RSC's 1984 production. It includes a new introduction in which Sher looks back at what has happened to him and to the world in the intervening years.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Year of the King by Antony Sher in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Acting & Auditioning. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1. Barbican 1983

August 1983

Summer.

To be more precise, my thirty-fourth summer in all, my fifteenth in England away from my native South Africa, my eleventh as a professional actor, and my second as a member of the Royal Shakespeare Company.

These last two years have been eventful, a time of change. Last year, a successful season in Stratford playing the Fool in King Lear and the title role in the Bulgakov play Molière. Then, in November, an accident. In the middle of a performance as the Fool one of my Achilles tendons snapped and I suddenly found myself off work for a period that was to last six months.

Unexpectedly, this proved to be a happy time. Apart from anything else, the enforced rest was a chance at last to do all those paintings and sketches I’d long been planning. With my leg encased in plaster I’d sit for hours at my easel, just managing now and then to hobble a few steps back to get a better view. If anything, time passed too quickly. After years in a profession where you’re on public display, it was a relief to be a recluse for a change. My temporary disability made any journey from my home in Islington difficult and vaguely humiliating, so few were worth it. There was one exception.

The Remedial Dance Clinic in Harley Street is so-called because it serves as repair shop to most of the dance companies. Each day I would have to make my way there for long sessions of physiotherapy. This was a new experience for me. Strange, invisible currents of electricity, ultra-sound and deep-heat were passed into my leg and somehow started it working again. The process was slow. When the plaster first came off, the white shrunken leg revealed underneath was virtually useless. But gradually, stage by stage, my crutches could be exchanged for a walking-stick, then that was abandoned for boots with stacked heels, and eventually I was walking again in ordinary shoes. Now the process accelerated in the other direction. Running, then jumping, even trying a cautious cartwheel . . . preparing to go back into King Lear for the London run at the Barbican Theatre.

Another treatment of a very different sort, which I decided to try while I had the free time, was psychotherapy. Here the currents are stranger, but just as impressive. A man called Monty Berman has been listening patiently to the story of my life, yawning only occasionally. He makes comments like ‘Let’s validate that’, when I relate certain chapters, and ‘Bullshit!’ to others. I sit there, peering at him through my large, tinted specs, nodding in agreement, and then hurry away afterwards to check words like ‘validate’ in the dictionary.

So the Achilles incident has been a kind of turning point. Invisible mending from head to heel. Now I also pay regular visits to the City Gym, the Body Control Studio, and various swimming pools. I have developed, along with new muscles and energy, that brand of smug boastfulness on the subject of physical fitness: the kind that makes other people – and I remember this well from being on the other side – want to slap you around the mouth.

Going back into King Lear after six months away was like climbing on to the horse after it has thrown you. But its short London run is already over and I escaped uninjured. I have since opened in a new production of Tartuffe, playing the title role. This has been directed by Bill Alexander (as a companion piece to his production about its author, Molière) and has been a great hit with audiences, although less so, I believe, with the critics. My uncertainty stems from the fact that, along with a whole string of unwanted habits ditched since going to Monty, I have stopped reading reviews. I never thought I could do it, never thought I could live without them. But now, apart from the occasional twinge, I hardly miss them at all. Rather like giving up cigarettes, I suppose. Unfortunately, I still smoke quite heavily. Which is just as well, as I’m required to do so in the new David Edgar play, Maydays, which is about to go into rehearsal . . .

In the meantime, at the Barbican, Tartuffe and Molière continue in the repertoire.

JOE ALLEN’S Dining with a friend one evening, I notice Trevor Nunn [RSC Joint Artistic Director] at another table. He’s been on sabbatical ever since I joined the RSC last year, so I haven’t met him properly. Yet he is the RSC, so a social gesture might be required. Is it just a little nod? Or a little wave? Or a little of each with a mouthed, ‘Hi, Trev’? Or as much as popping over to his table and using the more formal, ‘Trevor, hello’? Luckily, his back is to me at the moment, so none of these decisions will have to be taken till my exit. For the moment I can concentrate on my Caesar Salad.

Hours later, my companion goes to the loo and almost instantly, as if by magic, Trevor Nunn is leaning forward on to my table.

‘Tony.’

‘Trevor!’

‘I did enjoy Tartuffe the other evening.’

‘Ah. Good. Thank you.’

‘I thought Bill Alexander got a perfect balance in the production between the domestic naturalism and the black farce.’

‘Yes, hasn’t he? It’s a –’

‘You really ought to play Richard the Third soon.’

‘Oh. Well. That would be nice.’

I look up at him hopefully. He smiles politely, a touch of enigma, and retreats, disappearing into the smoky, gossipy crowd . . .

Back at home, Jim [Jim Hooper, RSC actor] says, ‘Beware. It’s only Joe Allen’s chat.’ He’s quite right, of course, so I try not to think any further about it. Which is like trying not to breathe.

There was something unfinished in what he said. ‘You really ought to play Richard the Third soon –’ what might he have said next? ‘And I shall direct it’? Or, ‘– but not for us’? In the next few days these nine words, this innocent piece of Joe Allen’s chat is subjected to the closest possible scrutiny. It is viewed from every possible angle, upside down and inside out, thoroughly dissected, at last laid to rest, exhumed, another autopsy, finally mummified.

I try not to tell people about it, but it does have a peculiar life of its own, this ghost, and will keep slipping out.

I make the fatal mistake of mentioning it to Mum on one of my Sunday calls to South Africa. She instantly starts packing.

Another mistake is to mention it to Nigel Hawthorne (playing Orgon) at the next performance of Tartuffe. He twinkles. From then on the shows are accompanied by comments like, ‘Thought I noticed Tartuffe developing a slight limp this evening’, or, overhearing me complaining about putting on weight, he says, ‘Can’t you just edge it up for the hump?’

This successfully helps to shut me up, so apart from Mum’s weekly question, ‘And Richard the Third?’, as if we were about to open, there is no further mention made of it.

Time passes. Now it is winter.

Thursday 3 November

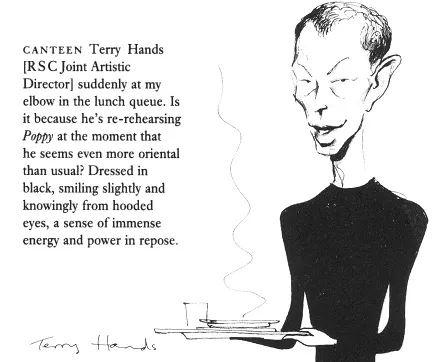

BARBICAN Paranoia is rampant these days, down in our warm and busy warren, miles below a chilly City of London. The end of the season, and for many their two-year cycle, is in sight. Rumours are rife about world tours of Cyrano and Much Ado, videos of Molière and Peer Gynt. Many are keen to return to Stratford where, rumour boasts, Adrian Noble will direct Ian McKellen as Coriolanus and either David Suchet or Alan Howard will be giving an Othello. But will people be asked back and, if they are, will good enough parts be on offer? It is widely believed that planning meetings are already in session in those distant offices above street level. As the directors pass among us for their lunches, suppers and teas, actors perform daredevil feats of balance in order to eavesdrop on conversations half a room away.

I am not above these feelings of unease myself. These years with the company have been the happiest of my career and I too don’t want them to end.

He says, ‘We really ought to have one of our meals soon.’

‘Absolutely. When?’

‘Well, I’m busy with Poppy technicals till the week after next. Has Bill spoken to you?’

‘No.’

‘Bill hasn’t spoken to you?’

‘No. What about?’

‘Oh, you know . . .’ He smiles. ‘Life and Art.’

‘Ah. No. Definitely not.’

‘We’ll let Bill speak to you first.’ He starts to go. Actors leaning towards us at forty-five degree angles quickly straighten, ear erections drooping. Terry turns back to me and smiles.

‘Oh, and don’t sign up for anything else next year. Yet.’

Friday 4 November

Bill Alexander rings. We arrange lunch for Monday.

MAYDAYS After the show, Otto Plaschkes comes round to my dressing-room. He’s a film producer, the latest in a long line to try to finance Snoo Wilson’s screenplay, Shadey. I was first approached about playing the eponymous hero (a gentle character who possesses paranormal powers and wants to change sex) over a year ago. I tell him I’m about to be talked to by the RSC, presumably about returning to Stratford. If he could be more definite about dates I could ask the RSC to work round them. He can’t, but it’s an encouraging meeting.

Sunday 6 November

Wake in the early hours. Meeting Bill tomorrow. It’s got to be Richard III. Got to be. Alan Howard’s was about three, four years ago, so it’s due again. And it’s the obvious one if they’re going to give me a Shakespeare biggy. Sudden flash of how to play the part – ideas are so clear in the middle of the night – Laughton in The Hunchback of Notre Dame. Very misshapen, clumsy but powerful, collapsed pudding features. Richard woos Lady Anne (his most unlikely conquest in the play; I’ve never seen it work) by being pathetic, vulnerable. She feels sorry for him, is convinced he couldn’t hurt a fly.

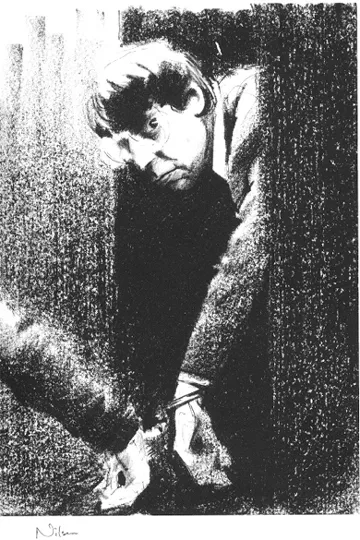

The Nilsen murder case – the Sunday papers are full of the trial of this timid little mass-murderer. The sick, black humour seems to have a flavour of Richard III: Nilsen running out of neckties as the strangulations increased; a head boiling on his stove while he walked his dog Bleep; his preference for Sainsbury’s air fresheners; his suggestion to the police that the flesh found in his drains was Kentucky Fried Chicken; even his remark that having corpses was better than going back to an empty house. The headlines squeal ‘Mad or Bad, Monster or Maniac, Sick or Evil?’

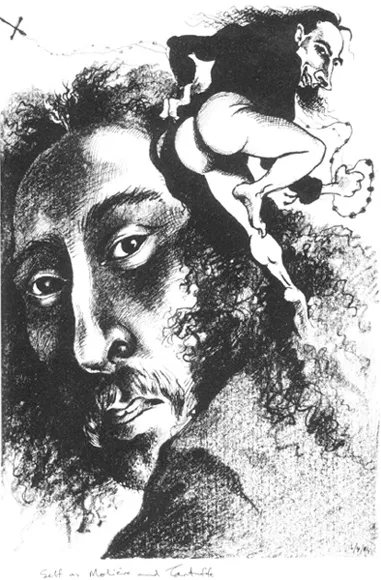

Spend hours sketching him, looking for some signs in that ordinary, ordinary face. The newspaper editors compensate for its ordinariness by choosing photos that are shot through police-van grills, or where the flashlights have flared on his spectacles to make him look other-worldly. But his ordinariness always seeps through. Isn’t it that which makes him really frightening?

I ask Jim whether he believes we all have a Nilsen within us. He says, ‘Well, certainly not you. You can’t boil an egg, never mind someone’s head.’

Monday 7 November

TRATTORIA AQUILINO Over lunch, Bill offers me Richard III. Although I’ve been expecting it, my heart misses a beat.

I don’t know whether Bill is any younger than the other directors, but he is somehow always regarded as such. After seven years with the company he is the only one titled Resident – rather than Associate – Director, his missing qualification being a Shakespeare production in the main auditorium at Stratford. In fact the only Shakespeares he’s ever done for the company were the Henry IV’s for the small-scale tour a couple of years ago. But after his successes this year with two classics (Volpone and Tartuffe) in The Other Place and The Pit this next step is inevitable.

We complement one another curiously, pulling in opposite directions – him towards the naturali...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Contents

- Introduction: April 2004

- 1. Barbican: August–December 1983

- 2. South Africa: December 1983

- 3. Acton Hilton, Canary Wharf and Grayshott Hall: January–April 1984

- 4. Stratford-upon-Avon: April–August 1984

- About the Author

- Copyright