![]()

Great Expectations

by Tanika Gupta

after Charles Dickens

English Touring Theatre and

Watford Palace Theatre on tour

![]()

Nikolai Foster was born in Copenhagen and grew up in North Yorkshire. He trained at Drama Centre London and at the Crucible, Sheffield.

He has been director on attachment at the Crucible, the Royal Court Theatre and the National Theatre Studio, and is an associate director of the West Yorkshire Playhouse, Leeds.

Nikolai has directed Merrily We Roll Along (Clwyd Theatr Cymru), The Diary of Anne Frank (York Theatre Royal and the Touring Consortium), All the Fun of the Fair (on tour), Flashdance (West End), A Christmas Carol (Birmingham Rep), Kes (Liverpool Playhouse and on tour), Amadeus and Assassins (Crucible), Aspects of Love (UK tour and Nelson Mandela Theatre, Johannesburg), and Annie, Animal Farm, Salonika and Bollywood Jane (West Yorkshire Playhouse).

![]()

‘The director’s job is to serve a play with imagination, intelligence and integrity, and challenge a text, his actors and collaborators, to create original work that is relevant to the world we live in.’

Nikolai Foster

![]()

Great Expectations

by Tanika Gupta after Charles Dickens

Opened at Watford Palace Theatre on 17 February 2011.

Creative

Director Nikolai Foster

Designer Colin Richmond

Lighting Designer Lee Curran

Composer Nicki Wells

Musical Advisor Nitin Sawhney

Sound Designer Sebastian Frost

Casting Director Kay Magson

Movement and Choreography Zoobin Surty and Cressida Carré

Fight Director Kate Waters

Associate Director Nicola Samer

Cast

Magwitch Jude Akuwudike

Compeyson Rob Compton

Herbert Pocket Giles Cooper

Jaggers Russell Dixon

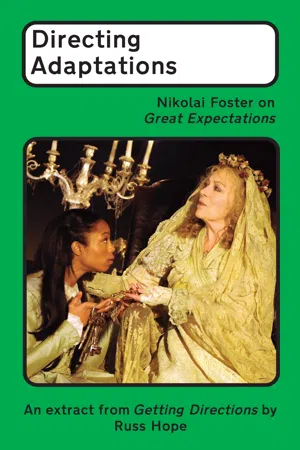

Miss Havisham Lynn Farleigh

Mrs Gargery/Molly Pooja Ghai

Estella Simone James

Joe Gargery Tony Jayawardena

Pip Tariq Jordan

Pumblechook Shiv Grewal

Wemick Darren Kuppan

Biddy Kiran Landa

![]()

A Director in Commercial Theatre When I meet Nikolai Foster in a tea shop in Soho, he is two hours off the train from the opening of his production of A Christmas Carol at the West Yorkshire Playhouse. He has an hour before he is due at the nearby Shaftesbury Theatre where his production of Flashdance opened a few months before, and before he goes home he will cram in a quick meeting for the production of Macbeth, which he is to direct in Singapore immediately after Great Expectations.

When Nikolai joins the production, the wheels are already in motion, and turning fast. The creative process is new, but the machine moves fast and has to be fed. Ideally, a director would have time to read and re-read a play and immerse himself in its world, but often the reality is that the director in touring theatre must acclimatise material fast to the familiar schedule: four weeks of rehearsal, three days of tech and the imperative that the set must fit in a lorry and be able to be constructed in three hours. Fortunately, with his experience in commercial theatre, where hiring the director can be the last piece of a puzzle that begins with producers, Nikolai is familiar with that often brutal framework, and with the process of creating space for an artistic process within it.

This play is Great Expectations, adapted from Charles Dickens’ novel by Tanika Gupta.

The production’s ‘big idea’ is to relocate the action from Victorian England to colonial India. Nikolai reflects that the scale of that decision affects his role on the project:

I don’t need to manufacture a ‘take’ on the material. The adaption is bold; so different from the Dickens we know. The location is so evocative. As a theatregoer, I would like to be transported to 1800s Calcutta. The idea of Miss Havisham as a colonial ex-pat meeting a young Indian boy is theatrically exciting... If I’m the student writing the school essay, I’ve got enough to consider – I don’t need the director making another statement on top of it. I would hate for that to sound lazy, but there is only so much concept a play can take. The play is the thing, and part of the director’s job is knowing how much or little of his hand a play can cope with. My job on this production is to keep the story moving and ensure that the scenes are truthful, detailed and exciting.

This is no small task. The script is heavy enough that it produces a thud when it lands on a table. It is a ‘beast’: a thirty-three-scene epic following twelve years of a life lived against the backdrop of a country moving towards the end of colonial rule. It is also a love story, a coming-of-age story, a story of political struggle and a treatise on class.

The production begins proper with a storyboard. This document, conceived alone by Nikolai, is a kind of scale model that posits the tone of the production and imagines the transition between scenes. On a prosaic level, that means how the production will get from scene to scene. More artistically, it means finding the tone of the production. If there are any moments in the script that don’t feel theatrical, Nikolai wants to find them first on the page.

Extract from the storyboard

Act 1, Scene 1

Setting: India, 1861

Entering the theatre, the audience is confronted with what appears to be a traditional front cloth. On closer inspection, this is a large series of individual pieces of material, stitched together by hand, to make a huge collage of colour and zigzag landscapes, which could be a map of the World.

A delicate shaft of light zips across the cloth, gently warming it and pulling out the hotchpotch of stitching. We can see nothing beyond. Nor can we hear anything.

Gently, the house lights start to fall away. Music is heard in the distance – perhaps a lone guitar? A fusion of electronic sounds? Whatever it is, it should be solitary, distant and thoughtful. Music fills the room and a lone female voice is heard singing on top of the music. It drifts through the warm air.

A single light/spot comes up behind the front cloth. A young boy, Pip, sits on his haunches. He stares into the distance, alone with his thoughts. He is almost frozen in time and space. We hold this image of the child and the warm light soaring above him as the music continues.

In the distance, a figure approaches. His hands and feet are shackled. There is a huge light-source directly behind the figure, which causes a terrific shadow to hit the back of the front cloth.

Two images: The boy on the ground with the light towering above him and the more abstract silhouette of a giant on the front cloth.

The music continues as the images hold our focus, only the voice fades away.

As the actors speak, the music becomes underscore and is much more menacing and fragmented.

Magwitch speaks and on his second line we start to open out the space to a much more naturalistic state.

As the lights illuminate the graveyard, we see skulls scattered about the floor. A pyre smokes gentle, upstage-left. (NB. The pyre needs to be practical so an actor can sit/stand on it.) It is difficult to make out what these objects are in the dim, hazy, silvery moonlight. There should be no sense of where the boundaries of this space are.

The scene should feel dreamlike and surreal. We are experiencing the scene through a child’s imaginative and distorted eyes. The underscore/sounds should continue throughout.

As Magwitch exits, the underscore starts to build and suddenly leaps into something dynamic and fast-moving (percussive?). It carries us through the fearful night, Pip’s nightmares, and into the calm of the next day.

Pip runs offstage.

Simultaneously, the scene shifts. Pip crosses the stage, pulling the front cloth with him as he goes, revealing the new scene and with this, the lights come up. (NB. This change must last no more than forty-five seconds.)

For Nikolai, a production is clearest when its tone and aesthetic comes from one mind. ‘The few times I’ve worked with someone who didn’t share the concept, it’s been the elephant in the room,’ he says, and so he builds a team that might ‘better’ his vision within the boundaries he has set. As soon as rehearsals begin, the storyboard is put away in search of something better.

The design, by Colin Richmond, is a poetic rendering of an Indian village (‘simple and uncluttered’) that will use light and music to bind its sparse environment together and drive the transitions between scenes. Seven doors, in colonial style, are suspended upstage and can be lowered to become functional. Three silk curtains on rails can be brought in to work with the lighting to define smaller spaces and imply, for example, the corridors of Miss Havisham’s crumbling mansion. The result is a production that will move at filmic speed, revealing locations as the curtain wipes across the stage.

The rehearsal room at English Touring Theatre’s building in South London is full with representatives from each of the tour venues: one more person and the atmosphere would tip into uncomfortable. Brigid Larmour, the artistic director of Watford Palace Theatre, invites the audience to enjoy ‘the particular magic’ of hearing a ne...