![]()

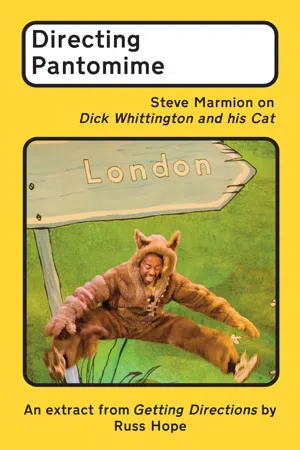

Dick Whittington and his Cat

by Joel Horwood,

Morgan Lloyd Malcolm

and Steve Marmion

Lyric Hammersmith

![]()

Steve Marmion is artistic director of Soho Theatre. His productions include Utopia, Fit and Proper People, Realism and Mongrel Island (Soho Theatre), Macbeth (Regent’s Park Open Air Theatre), Edward Gant’s Amazing Feats of Loneliness (Headlong), and the Broadway transfer of Rupert Goold’s Macbeth.

Steve was an associate director at the RSC from 2006 to 2007, and has worked with the National Theatre, Royal Court, Theatre Royal Plymouth, Theatre Royal Bath, Watford Palace Theatre, Sherman Theatre Cardiff and at the Edinburgh Festival.

![]()

‘As directors, our job is communication and our currency is the actor and the script. We have the smoke and mirrors of spectacle, yes, but what is more important is learning the skill to get an actor or a writer around that problem or over that hurdle.’

Steve Marmion

![]()

Dick Whittington and his Cat

by Joel Horwood, Morgan Lloyd Malcolm and Steve Marmion

Opened at the Lyric Hammersmith, London, on 27 November 2010.

Creative

Conceived and Directed by Steve Marmion

Designer Tom Scutt

Lighting Designer David Holmes

Music Tom Mills

Sound Designer Nick Manning

Choreographer Lainie Baird

Musical Director Corin Buckeridge

Associate Director Daniel Herd

Cast

Scaramouche Nathan Byron

Mr Fitzwarren/The Prince Kulvinder Ghir

Alice Fitzwarren Rosalind James

King Rat Simon Kunz

The Cat Paul J. Medford

Sarah the Cook Shaun Prendergast

Dick Whittington Steven Webb

Bow The Voice of Stephen Fry

Bells The Voice of Alan Davies

Ensemble Elizabeth Alabi, Joanna Bateson Hill, Zofzjar Belsham, Alice Brazil-Burns, Hugo Joss Catton, Eysis Clacken, Christian Geddes, Tara-Jessica Hollingsworth, Freddie Jacobs, Ellis McNorthey-Gibbs, Glenn Matthews, Karl Queensborough, Deanna Rodger, Tatiana Romanova, Sam Thompson and Bertie Watkins

![]()

There is an old joke. A veteran actor takes a job in pantomime. One night, as he straps on the back-end of a panto horse, he wonders aloud what happened to his career. A wag replies: ‘It’s behind you!’

Towards the end of the 1970s, the subsidised theatre all but stopped making pantomimes. For over a hundred years, pantomimes, with their bawdy dames, slop scenes and raucous singalongs, were as much a part of Christmas as turkey dinners and family arguments. But today, they are more likely to be seen in village halls and in thousand-seat commercial playhouses, and little in between.

A love of pantomime is a matter of taste or, depending on who you talk to, lack of taste. Disregard for the form runs so high in some circles that the word ‘panto’ itself has changed its meaning, from a description of a particluar form of theatre, knowable by strict, if baggy, collections of narrative rules and aesthetic principles, to a verb to describe all that might be lazy in a production. An audience might say of an actor who pulled one too many faces that he ‘pantoed’ his way through a scene.

But for the director Sean Holmes, the word ‘panto’ speaks of fantastic stories, performed with full hearts for an audience drawn from every corner of the community – old and young, artist and artisan. When Sean took over as artistic director of the Lyric Hammersmith in 2009, he instituted an artistic policy, two of whose commandments are to ‘lurch wildly between high art and populism (hopefully achieving both at the same time)’ and the call to action: ‘Hammersmith and proud.’ At the intersection of these commandments, he would place panto. Every Christmas, the Lyric would become a village hall, welcoming the entire community and asking it to be unreservedly joyful and silly in its appreciation.

The Lyric pantomime would also be done with ‘a bit of class,’ Sean says. The script would be written by young but experienced playwrights, performed by working actors (rather than TV celebrities), and given a ‘proper’ rehearsal period, rather than the handful of days often afforded to commercial pantomimes.

Sean entrusted the Lyric pantomime, its first in thirty years, to Steve Marmion, a thirty-two-year-old director who assisted him at the RSC years before, and whose professional mottos are: ‘Thou shalt not bore’ (inspired by the theatre polymath Anthony Neilson) and ‘Thou shalt not leave thy audience feeling stupid.’

Pantomime is to Steve an ‘intellectual fascination’ that started with a love of football. ‘Theatre and football are essentially the same event,’ he explains when we first meet. On any given Saturday, thousands of people attend the theatre. They laugh or weep quietly, gripping the arm of the person next to them. Meanwhile, football stadiums are filled by hundreds of thousands of grown men, shouting, crying and singing with abandon as the spontaneous narratives of injury-time goals, or players scoring against their old clubs move them to higher levels of joy or grief. Our rational side knows that this response is absurd, Steve reasons. The football crowd knows that to cry and shout as two teams kick a ball around a rectangle of grass makes no sense. No more than allowing one’s self to believe that an actor is the character he pretends to be. In each case, it is the structure of the event that allows us to care, and incites us to join in. The difference between theatre and football, Steve explains, is that often the further you move from sports towards intellectually challenging theatre, the more ‘the emotional connection is allowed to diminish, or at least to display itself with reserve’. Steve hasn’t the nerve for karaoke, he says, but he’ll stand with the ‘hairy-arsed Scousers’ at Anfield and belt his team’s anthem, which happens to be a song from a Rodgers and Hammerstein musical, ‘You’ll Never Walk Alone’.

What makes otherwise ‘level-headed’ crowds express their emotions with such abandon at a football match and not at the theatre? ‘The simple answer is that the social rules are different,’ Steve says. ‘The rules of football encourage us to sing and shout. The rules of theatre suggest we don’t. Unless it’s a panto.’

Dick Whittington is the story of a wide-eyed country lad who pursues his fame and fortune to London, a magical city, he has heard, where the streets are paved with gold. Instead, Dick finds the city infested with rats. He finds work at a local bakery run by Mr Fitzwarren, a local curmudgeon. There he meets the bakery’s cook, Sarah, and Mr Fitzwarren’s daughter, Alice, with whom he falls in love. From there, the plot depends on the teller, although the story has essential ingredients: the bells of St Mary-le-Bow – the famous Bow Bells within whose earshot the true Cockney is born – must call Dick to his destiny as Lord Mayor of London; there must be a voyage by ship that strands the characters in a far-off kingdom where Dick becomes a hero after his cat clears an infestation of rats from the palace of the island’s king. The story must end with Dick returning to London with untold riches, whereupon he marries Alice and, as the Bow Bells peal, is appointed Lord Mayor of London.

The story, like all enduring pantomime stories, is an eternal tale of love, power and control. ‘Shakespeare in glitter,’ Steve says.

I think we can challenge people on why they want the things they want. In these days of reality TV, more people say that what they want is fame, but fame and riches are not, in themselves, worthy ambitions. To have enough money that you can provide for the people you care about, on the other hand, and to be recognised for having added value to the world, is a wonderful ambition.

If a production can combine that ‘politically valuable moral core’ with an escapist roller-coaster, then the audience might even listen.

Ask ‘What is theatre?’ and we’ll be here all day. Even then, we may not agree on a definition. But ask ‘What is pantomime?’ and the answer is a little easier. We know a pantomime by certain structural and tonal rules, cobbled together over a hundred years, and without which we may have a piece of theatre – we may even have the story of Dick Whittington and his cat – but it won’t be the pantomime version of the story. To be the panto version of the story, our production must:

• Be set in a romanticised vision of the local community, celebrated in song by a chorus of townspeople.

• See love triumph and villains redeemed.

• Have its villain enter from stage-left, and its hero from stage-right.

• Feature original songs and parodies of the popular songs of the day, and a singalong with lyrics printed on an enormous song sheet.

• Contain slapstick.

• Revel in double entendre.

• Challenge the audience into call and response with the characters.

• Feature a dame, which is a man in matronly drag who makes risqué jokes and throws sweets into the audience.

• Allow the actors to acknowledge the audience’s presence whilst remaining in danger within the story.

• At some point, bring a child from the audience onstage.

Dick Whittington and his Cat will be written by the playwrights Joel Horwood and Morgan Lloyd Malcolm, with Steve overseeing as deviser and conceiver. Joel, Morgan and Steve begin by tipping each component of the traditional panto onto the floor and examining each in turn, asking whether it is useful, relevant and fun before putting it back in the box.

Some traditions survive, such as the tradition that scenes alternate between those played in front of brightly coloured show-cloths, and those played among elaborate sets that use the full expanse of the stage. Decided upon before the days of flying and automated scenery, this tradition is no longer necessary, but as it can create a hurtling momentum, the team are eager to keep it. Traditions marked for extinction include the convention that the lead boy is played by a female actor, which, the team feels, lessens the drama. Some conventions are given suspended sentences, such as the convention that a child is brought onstage from the audience, which will survive only if the interaction can be made to affect the story, most likely by transforming the participant into the ‘adventure consultant’ who gives the characters the key to solving a grave problem they have.

Steve works the traditional story into a grid of scenes that he presents to Joel and Morgan. The group revises the grid until they are happy with the plot, then Joel and Morgan draf...