![]()

Ian McKellen

on

King Lear

King Lear (1605–6)

Royal Shakespeare Company

Opened at the Courtyard Theatre, Stratford-upon-Avon on 31 May 2007

Directed by Trevor Nunn

Designed by Christopher Oram

With Frances Barber as Goneril, Monica Dolan as Regan, Romola Garai as Cordelia, William Gaunt as the Earl of Gloucester, Jonathan Hyde as the Earl of Kent, Sylvester McCoy as the Fool, Ben Meyjes as Edgar, and Philip Winchester as Edmund

King Lear was written around 1605, between Othello and Macbeth, when Shakespeare was at the height of his powers. It was subsequently revised, and therefore two distinct versions exist. The earlier text was published, rather badly, in quarto in 1608. The later, a slightly shorter and more theatrical version, was included in the 1623 First Folio. Editors and theatre directors often conflate the two.

‘No man will ever write a better tragedy than Lear,’ wrote Bernard Shaw, and A.C. Bradley called King Lear ‘Shakespeare’s greatest achievement’. However, it has not always been popular. After the English Civil War the play fell out of fashion. Its portrayal of abject cruelty and senseless brutality was too painful for audiences to bear. In 1681 Nahum Tate produced a sentimentalised reworking of the play, giving it a happy ending in which Lear and Cordelia are left alive and she marries Edgar. Throughout much of the eighteenth century, audiences preferred this version. But since the nineteenth century, Shakespeare’s original has been regarded as one of his supreme achievements. By the 1960s, following the Holocaust and the two World Wars, the graphic violence no longer appeared far-fetched. Gloucester’s line ‘As flies to wanton boys are we to th’ gods; / They kill us for their sport’ [4.1] seemed in tune with the times. Peter Brook’s iconic 1962 production was influenced by the critic Jan Kott, who compared King Lear to the ravaged scenarios of Samuel Beckett’s Endgame and Waiting for Godot, commenting that ‘the abyss, into which one can jump, is everywhere’.

The mainspring of the play is Lear’s folly in passing control of his kingdom to Goneril and Regan, moved by their flattery, and disinheriting Cordelia – the daughter who truly loves him. This sets in motion the tragic events that follow. Goneril and Regan betray their father and throw him out into the cold. The homeless Lear wilfully exposes himself to a thunderstorm, comparing nature’s mercilessness to his daughters’ treatment of him. Regan’s husband Cornwall plucks out Gloucester’s eyes; war erupts between England and France; Goneril poisons her sister Regan in jealous rivalry over Gloucester’s bastard son Edmund, and then kills herself. Cordelia is put to death by order of her sister’s lover, causing Lear to die of a broken heart. His entire family ends up dead.

A parallel subplot echoes the theme of conflict and treachery, as opposed to love and respect, between parent and child. It involves the Earl of Gloucester and his two sons: the villainous bastard Edmund cares only for his own prosperity and sensual fulfilment, and plots to destroy the innocent Edgar. The play explores an intricate web of related topics: family relationships collide repeatedly with politics, and the nature of human suffering is persistently examined.

Ian McKellen and Patrick Stewart are the only contributors to both volumes of Shakespeare On Stage. Besides being superb actors, they both have exceptional theatrical intelligence, and talk about their work with wonderful insight and articulacy. I was thrilled when Ian agreed to be interviewed about King Lear. He was refreshingly suspicious of assumptions. Whereas Lear’s madness is normally taken for granted, he repeatedly examined the character’s actions, saying ‘Hang on a minute: is that mad, or is it sane?’ He likewise rejected the ‘bleakness’ label that is so often attached to the play, citing many positive elements, and remains unsympathetic to Jan Kott’s nihilistic reading. The chapter ends with Ian saying: ‘Directors are tempted to reduce the play, or to say it’s about this or that, when in fact it’s about everything.’ We met for this interview in 2013 at his riverside home in Southwark. It was the day after the memorial service for our good friend Roger Hammond, to whom Ian refers.

Early in 2017 it was announced that Ian was about to play Lear again, in a new production. I was surprised, as it is very unusual for him to reprise a part. He explained ‘Many actors have had more than one go at Lear. In my case, I want to discover the intimacy of the play – as I did with Macbeth in a series of small theatres and with Richard III on screen – by presenting it in the Minerva Theatre at Chichester.’

Julian Curry: Trevor Nunn has directed King Lear at least three times, and you’ve acted other parts in other productions, but I think this is the first time you’ve played the lead.

Ian McKellen: Yes, I’d seen both his previous ones and enjoyed them enormously, and was touched that he wanted to delve into it all again with me. We’d had an arrangement if ever I was invited to play it I would ask him to direct, and vice versa. And when the time came he honoured that agreement.

Lear’s a hell of a part. It requires, they say, a young man’s stamina with an old man’s experience and skill. So the danger is by the time you’re old enough to play it, you’re too old to play it. You were sixty-eight, I think: did that feel about right?

It did, yes. Lear says he’s eighty or more, doesn’t he, which in Shakespeare’s time would have been extremely old. Here I am five years later thinking about old age, and probably having been in the production makes me more at ease with being old than I was before. I’m aware of the significance of illness, of an accident, a trip. As we talk I’ve just been fitted with hearing-aids in both ears, I wear glasses, I’ve had a cataract done, I’ve had some implants and I’ve got prostate cancer. I don’t believe five years ago I would have talked about these things, or have accepted them in terms of decrepitude. But I think of this now as survival, because I feel more positive about being old. There is at the end of the play a sense that the terrible things that have happened to Lear, and that he has visited on other people, have taught him something about ways in which old age can be viewed. At the outset, Lear is an old man who people talk to with a sense that if you’re old you’re foolish, rather than venerable and wise. So the actor is probably going to have to face up to his feelings about age – not just his own, but of people he knows in his family and elsewhere.

I see.

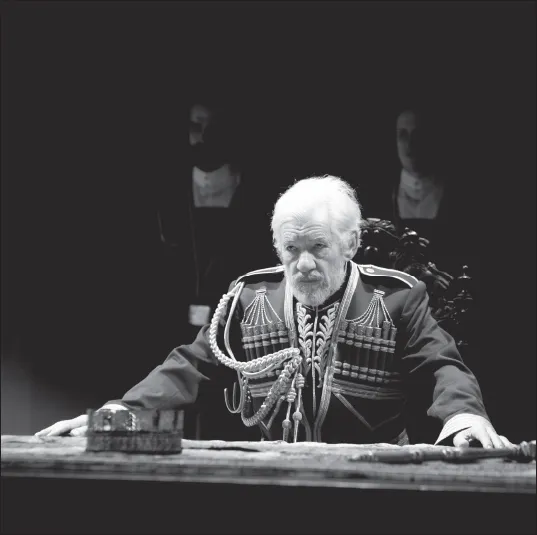

But talking about the age at which you play it, it isn’t much of a sitting-down part. Kings usually get chairs to sit on, but once you’re out of the court, which is pretty early on, Lear is always travelling around. Therefore I made a point of asking Trevor if I could sit down. Because if you’re old you like to. So wherever I went, an obliging servant would carry a box or something for me to sit on. I was very grateful for that. There’s a big gap for the actor playing Lear in the middle of the play when he’s not on stage, which is most welcome. The same is true of Hamlet. And unlike, say, Macbeth who also has his break, you don’t have to come back at the end of King Lear and do a fight. It’s a steady decline. You sit on the ground of course in the latter scenes. Then you’ll probably be in a chair or a wheelchair, or be helped about the place, and serenity is taking over.

Nonetheless, it’s a highly demanding part physically and vocally. How did you prepare? Did you work out in a gym?

Oh I don’t know, I do on the whole go and get pulled around. I knew it would be physically demanding; it was for the Royal Shakespeare Company and I think a tour was planned and probably a London season. It was a long commitment, and very early on, Trevor and I agreed that I shouldn’t play the part more than four times a week. So we did it in repertory with Chekhov’s The Seagull, in which I played Sorin, a relatively small but crucial part, that I shared with the actor playing Gloucester. Therefore the two old men from King Lear got to be in The Seagull but not every night. On a schedule of eight performances a week, I did four Lears, two Sorins and had two performances off, sometimes an evening off. And very rarely did I do two performances on one day, which was a huge help. Nonetheless, Lear is a great old mountain to clamber up. Big demands are made of you physically and emotionally, and when the two go together you’re likely to hurt your voice. I found when I didn’t know what to do in rehearsal I just shouted. Why should Lear ever shout? I was very, very clumsy with the part, and I’m sure learnt a great deal as we went along. It was a bane of the job that we were often in too-large theatres, where you need so much more stamina. I’m convinced we would all have given better performances if we’d been in a theatre as small and intimate as where the play was first performed. You know, the Globe and many of those theatres were smaller than we imagine.

You were in Trevor’s productions of Othello and Macbeth, both in small theatres.

There you go.

Lear, presumably, was in big theatres for the logistics of a long tour, to pack in the crowds.

Yes, exactly. Which is absolutely the worst reason to be in a big theatre.

So it wasn’t an artis...