![]()

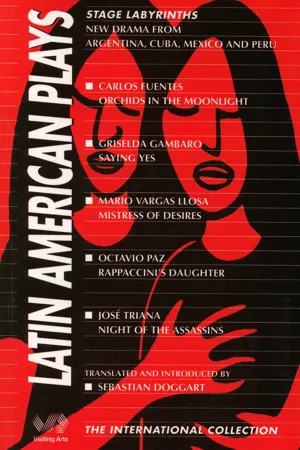

by Carlos Fuentes

![]()

Production Notes

1)Both women are of an indefinite age, between thirty and sixty years old. At some moments they are closer to the first age; at others, to the second. Throughout the play, DOLORES dresses like a stylised Mexican campesina: plaits gathered round her head in a bun tied together by rose-coloured ribbons, bougainvilleas behind her ears, rustic clothes made of percale, ankle-length boots and a shawl. MARIA, on the other hand, changes costume several times. The physical characteristics of the women are not fixed. Ideally, the roles will be played by María Félix1 and Dolores del Río.2 Even more ideally, they will alternate in the roles. In their absence, they can be played by actresses who are like them: tall, slender, dark, with distinctively sculpted bones, especially in the face: high and shining cheekbones, sensual lips quick to laughter and anger, defiant chins and combative eyebrows. This does not prevent the perversion, if necessary, that the roles should be played by two rosy-cheeked, blond, plump women. As a last resort, and in the absence of all the above-mentioned possibilities, the protagonists can be two men.

2)The set is conceived as a territory shared and constantly disputed by the two women. MARIA identifies with the style of certain objects and decorations: white bear skins, a white satin divan, a wall of mirrors. DOLORES stresses her possession of rustic Mexican furniture, paper flowers and clay piggy banks. Each possesses, on opposite sides of the set, a small altar dedicated to herself on which are photographs, posters of old films, little statues and other prizes. The common territory is a vast wardrobe upstage, made up of mobile clothes rails like the ones found in hotels and receptions. Hanging there are all types of clothes imaginable, from crinoline to sarong, from the customary national dress of Mexico to Emmanuel Ungaro’s latest collection. They are all costumes that the two actresses have used during their long screen careers. Downstage left is a metallic, prison-like door. Centre-stage, in front of the wardrobes, is a white toilet with a white telephone on the seat. C.F., 1982

![]()

Orchids in the Moonlight was written in 1982. This translation was first staged by the Southern Development Trust on 9 August 1992 in the Teatro Nacional, Havana, Cuba, and then had its British premiere at the Richard Demarco Gallery Theatre, Edinburgh on 17 August 1992.

MARIA | Tanya Stephan |

DOLORES | Tami Hoffman |

FAN | Simon Taylor |

| |

Director Sebastian Doggart | |

Designer Clare Brew | |

Producers Pippa Harris & Ian J. Clarke | |

![]()

Characters

MARIA

DOLORES

THE FAN

NUBIAN SLAVE GIRLS

MARIACHIS

Setting

Venice, the day Orson Welles died.3

![]()

The area lit is downstage centre. DOLORES sits next to a walnut colonial table, covered by a worn paper tablecloth, earthenware crockery from Tlaquepaque, paper flowers and a jug of fresh water. DOLORES stares intently at the audience for thirty seconds, first quite challengingly, arching her eyebrows; but gradually losing her self-confidence, lowering her gaze and looking to her left and right as if she were expecting someone. Eventually, her hands trembling, she pours herself a cup of tea, raises it to drink, looks back at the audience, again first challengingly, then in terror. She drops the cup noisily and stifles a piercing scream, the theatricality of which is drowned out by real tears. She groans several times, throwing her head back against the chair, raising one hand to her brow, covering her mouth with the other, trembling. From between the clothes rails upstage MARIA appears, slowly, moving with the enormous contained tension of a panther. Her dark flowing hair falls over the fur collar of a gown of thick brocade, which looks copied from the czar’s robes in Boris Godunov. MARIA walks towards DOLORES, adopting an air of pragmatism; she arranges her hair, puts on the gown and kisses DOLORES from behind. DOLORES responds to MARIA’s embrace by stroking her hands and trying to move her face closer towards her.

MARIA. It’s very early. What’s wrong?

DOLORES. They didn’t recognise me.

MARIA. Again?

DOLORES. I was sitting here having my breakfast, and they didn’t recognise me.

MARIA sighs and kneels down to pick up DOLORES’ cup and breakfast plate. The helpless trembling of DOLORES’ voice is replaced by a very faint tone of supremacy. MARIA’s presence is enough to cause this.

DOLORES. They recognised me before.

MARIA. Before?

DOLORES looks scornfully at MARIA kneeling down.

DOLORES. They asked for my autograph.

MARIA. Before.

DOLORES. I couldn’t go out to a restaurant without a crowd gathering to look at me, undressing me with their eyes, asking for my autograph . . .

MARIA. We haven’t gone out. (DOLORES looks at MARIA, silently interrogating her.) I mean we’re alone.

DOLORES. Where?

MARIA. Here. In our apartment. Our apartment in Venice.

She pronounces the proper name in an atrocious imitation of an English accent: Ve-Nice, Vi- Nais.

DOLORES (correcting her patiently). Vé-nice, Vé-Niss. How do you say Niza in French?

MARIA. Nice.

DOLORES. Well, now you add a Ve. Ve-Nice.

MARIA. The point is, we’re alone here and we haven’t gone out. Don’t confuse me.

Amazed, DOLORES crouches down to get closer to MARIA’s face.

DOLORES. Can’t you see them in front there, sitting down looking at us?

MARIA. Who?

DOLORES stretches out her arm dramatically towards the audience. But her wounded and secretive voice seems out of tune with her choice of words.

DOLORES. Them. The audience. Our audience. Our faithful audience who have paid in ready money to see us and applaud us. Can’t you see them sitting in front there?

MARIA laughs, checks herself so as not to offend DOLORES, tosses her head and starts to take off DOLORES’ Indian sandals.

MARIA. Let’s get dressed.

DOLORES. I’m ready now.

MARIA. No. I don’t want you to go out barefoot. (She puts her cheek next to DOLORES’ naked foot.) You hurt yourself last time.

DOLORES. A thorn. That’s nothing. You took it out for me. I love it when you take care of me.

MARIA kisses DOLORES’ naked foot. DOLORES strokes MARIA’s head.

DOLORES. Where are you going to take me today?

MARIA. First promise me that you won’t go out barefoot again. You’re not a Xochimilco Indian. You’re a respectable lady who can hurt her feet if she goes out into the streets with no shoes on. Promise?

DOLORES (nodding). Where are you going to take me today?

MARIA. Where would you like to go?

She starts to put some old-fashioned boots on DOLORES.

DOLORES. Not to the studios.

MARIA. To the film museum?

DOLORES. No, no. It’s the same. They don’t recognise us. They say we’re not us.

MARIA. So what? We don’t have to be announced.

DOLORES. They just don’t treat us the way they did before, they don’t reserve the best seats for us . . .

MARIA. So what? We sit in the darkness and we see ourselves on the screen. That’s what matters.

DOLORES. But they don’t see us now.

MARIA. That’s better. That way we see ourselves like the others see us. Before we couldn’t. Remember? Before we were divided, looking at ourselves on the screens like ourselves while the audience was divided, wondering: shall we watch them on the screen or shall we watch them watching themselves on the screen?

DOLORES. I think the most intelligent preferred to watch us while we were watching ourselves.

MARIA. Yes? Why?

DOLORES. Well, because they could see the film again many times, and many years after the opening night. On the other hand, they could only see us that night, the night of the première. Remember? Wilshire Boulevard . . .

MARIA. The Champs Elysées . . .

DOLORES. The spotlights, the photographers, the autograph hunters . . .

MARIA. Our cleavages, our pearls, our white foxfurs.

DOLORES. Our fans.

MARIA (in...