![]()

Chapter 1

ART, CULTURE, AND NEW YORK CITY

In 1977, a graffiti duo with the name of SAMO (standing for Same Old Shit) began bombarding New York subways and slums. It was the height of graffiti’s hold on the city, with thousands of kids running through subway tunnels deep into the night, away from cops and into subway yards where they spent hours painting masterpieces and signature tags on the sides of the subway cars so that, come morning, the trains would barrel through the city displaying their names and artwork like advertisements to anyone waiting on the platform. Thousands of kids wrote graffiti through their teenage years, only to put aside their artistic leanings by the time they reached their twenties, remaining unknown and invisible to anyone who didn’t ride the New York subway system during the 1970s and ’80s.

But SAMO was different. Still living in the gritty East Village, working and DJ-ing at downtown clubs, by 1981, one-half of the duo, Jean-Michel Basquiat, had attained recognition in the art world as the “Radiant Child” in ArtForum magazine. By the early eighties, Basquiat was being shown alongside Julian Schnabel, David Salle, Francesco Clemente, and Keith Haring. Between 1982 and 1985, Basquiat dated a then little-known musician named Madonna, began working with Andy Warhol, was shown by the starmaker gallery owner Mary Boone (his paintings sold for over $20,000), and landed on the cover of the New York Times Magazine. In 1988, he died of a heroin overdose. He was twenty-seven years old. Basquiat’s paintings are still worth thousands and thousands of dollars, and he is still considered one of the pivotal figures in New York’s postmodern, Neo-expressionist art world. Basquiat’s life, from his early days as an anonymous graffiti writer to the gritty East Village art and nightlife scene he thrived in, to meeting Mary Boone and Andy Warhol (who radically changed and catapulted his career) is emblematic of the central reason that New York City remains one of the global centers of creativity. In New York, such things happen, and in New York, creativity and creative people are able to succeed.1

Basquiat’s life, while tragically short, is illustrative of the mythology of artistic creativity. Fashion, art, and music are fun. They are, after all, the industries that drive celebrity and create those ephemeral and elusive qualities of glamour, sexy, and cool. And how they attain these qualities is often impossible, if not downright arbitrary, to predict. Putting value on Mark Rothko’s painting or Manolo Blahnik’s latest sky-high stiletto is not easy. It’s not clear what makes Marc Jacobs’ Kurt-Cobain-meets-hot-librarian sweatshirts and dresses so appealing, but that doesn’t stop thousands of women around the world from purchasing them in bulk. And people like Marc Jacobs as a person too (people who’ve never actually even met him). They read about his clothes in Anna Wintour’s editorials in Vogue, they follow his social life in gossip magazines and columns. The same can be said of any number of creative people, from Quincy Jones to Jay-Z to Diane von Furstenberg—or, more broadly, “cultural producers”—those who create and produce the art and culture consumed by both mass and niche markets.

But this is not just a book devoted to talking about how fashion, art, and music are interesting and fun. For that, you can read SPIN or Vogue or ARTnews. Instead, The Warhol Economy is about how and why fashion, art, and music are important to New York City. Despite the random and seemingly arbitrary processes that lead to the success of a music single or a new designer, a pattern emerges: a preponderance of creativity on the global market—and successful creativity at that—comes out of New York City. Why is that?

On a basic level, it’s clear that art and culture happen in particular places—New York, Paris, London, Los Angeles, Milan. Parties and clubs and high-profile restaurants are often cited in tandem with the celebrities that frequent them. Entertainment—whether Fashion Week or the MTV Music Awards show—generates lots of money and, if we think a little more, probably lots of jobs. But much of our understanding of art and culture is taken for granted at best, superficial and inconsequential at worst.

Worst because we view the role of art and culture as insignificant and not as a meaningful part of an urban, regional, or national economy. We take it as more fun and less business. And so, although policymakers and urban economists are versed in the mechanics of urban economies or how we think cities work, the role of art and culture is left out of this basic paradigm of city growth and vitality, why some cities are more or less successful than others, and what components are necessary to generate great, vibrant places where people want to live.

Most students of New York see it as a center of finance and investment and understand the city’s economy as evolving from industrial production to the FIRE industries (finance, insurance, and real estate) that form its foundation today. And yet, for the better part of the twentieth century and well before, New York City has been considered the world’s authority on art and culture. Beginning with its position as the central port on the Atlantic Ocean, New York has been able to export and import culture to and from all parts of the globe. By the middle of the twentieth century, New York was the great home of the bohemian scene, beat writers, and abstract expressionists and later, to new wave and folk music, hip-hop DJs, and Bryant Park’s Fashion Week. As Ingrid Sischy, editor-in-chief of Interview magazine, remarked, “Before Andy [Warhol] died, when Andy led Interview you’d run into people who would say, ‘I came to New York because of Interview. I read it when I was in college, lonely and alienated and it made me feel not alone. I wanted to come there and be a part of that world’.” High-brow, low-brow, high culture, and street culture, New York City’s creative scene has always been the global center of artistic and cultural production.

Well, it’s New York. But what underneath that cliché propels the greatest urban economy in the world? New York’s cultural economy has sustained itself—despite increasing rents, cutthroat competition, the pushing out of creative people to the far corners of Queens and Philadelphia. Within its geographical boundaries are the social and economic mechanisms that allow New York to retain its dominance over other places. As the Nobel Prize–winning economist Robert Lucas pointed out, great cities draw people despite all of the drawbacks of living in a densely packed, noisy, expensive metropolis, because of human beings’ desire to be around each other. It is the inherent social nature of people—and of creativity—that makes city life so important to art and culture.

Central is the assumption that cultural economies operate differently from other industries. What we traditionally think of as the lure of New York City for business is different for those who produce art and culture. The central tenets of successful urban economies (the density of suppliers, the closeness of a labor market) are indeed important to fashion, art, and music, but they manifest themselves in a different way. For finance, law, manufacturing, and other traditional industries, these systems and mechanisms are pretty straightforward and, for the most part, operate within a formal, rigid structure. Economists often talk of the agglomeration of labor pools, firms, suppliers, and resources as producing an ensuing social environment where those involved in these different sectors engage each other in informal ways (they hang out in the same bars, live in the same neighborhoods, and so on). But this informal social life that economists often hail as a successful by-product (what they call a positive spillover or externality) of an economic cluster is actually the central force, the raison d’être, for art and culture. The cultural economy is most efficient in the informal social realm and social dynamics underlie the economic system of cultural production. Creativity would not exist as successfully or efficiently without its social world—the social is not the by-product—it is the decisive mechanism by which cultural products and cultural producers are generated, evaluated and sent to the market (more on this in chapters 4 and 5).

The cultural economy operates far from the boardrooms and skyscrapers that pack Manhattan’s geography. The evaluation of culture occurs in the tents in Bryant Park during Fashion Week, the galleries in Chelsea, the nightlife of the Lower East Side, or the clandestine nooks in SoHo, Chelsea, or the Meatpacking District that house nightclubs, lounges, and restaurants with bouncers who could be mistaken for Secret Service agents. In these haunts—often exclusive—the cultural economy works most efficiently. Culture is about taste, not performance, and so, unlike a dishwasher or a computer or even a car, there is no method or even means to evaluate how well it performs. We do not make decisions about pieces of art or music to listen to or (for many women) dresses to wear, based on how well they work. We buy these things because we like them . . . for some reason. And that reason is, very often, because it has been given value by experts—someone or some people or some organization or gallery or newspaper—that has the credibility to crown a dress, a painting, or a new music single with the approval and the cachet that make it worth wearing, buying, or listening to. These people are the gatekeepers, the tastemakers, the “connectors,” to use Malcom Gladwell’s term. They tell us what is worth having, what has taste, in a seemingly arbitrary, symbolic, and status-driven economy.

Fashion designer Diane von Furstenberg and her creative director Nathan Jenden at the end of one of her runway shows during New York Fashion Week. Photographer: Dan Lecca. Courtesy DVF Studio.

Tastemakers and gatekeepers spend a lot of time in the social realm—they (and the creative people who also thrive in the social life of New York) give meaning to a world that many people think of as frivolous, superficial, or filled with beautiful people who have nothing to say. It is the social life of creativity—from industry parties to 2 a.m. nights at Passerby or the Double Seven—that is the central nexus between culture and commerce. It is in this realm that creative people get jobs, meet with editors and curators who write reviews and organize exhibitions and shows. Designers like Dior’s Hedi Slimane or the late Stephen Sprouse plug into the nightlife scene to become inspired for their next collection; simultaneously business deals across creative industries are made while just hanging out late into the night. When Vanity Fair asked Slimane who the most stylish woman in the world is, he replied, “Some unknown girl on the dance floor.”2 It is this seemingly informal social world that drives and sustains the cultural economy, and it is why New York has been able to maintain its creative edge decade upon decade.

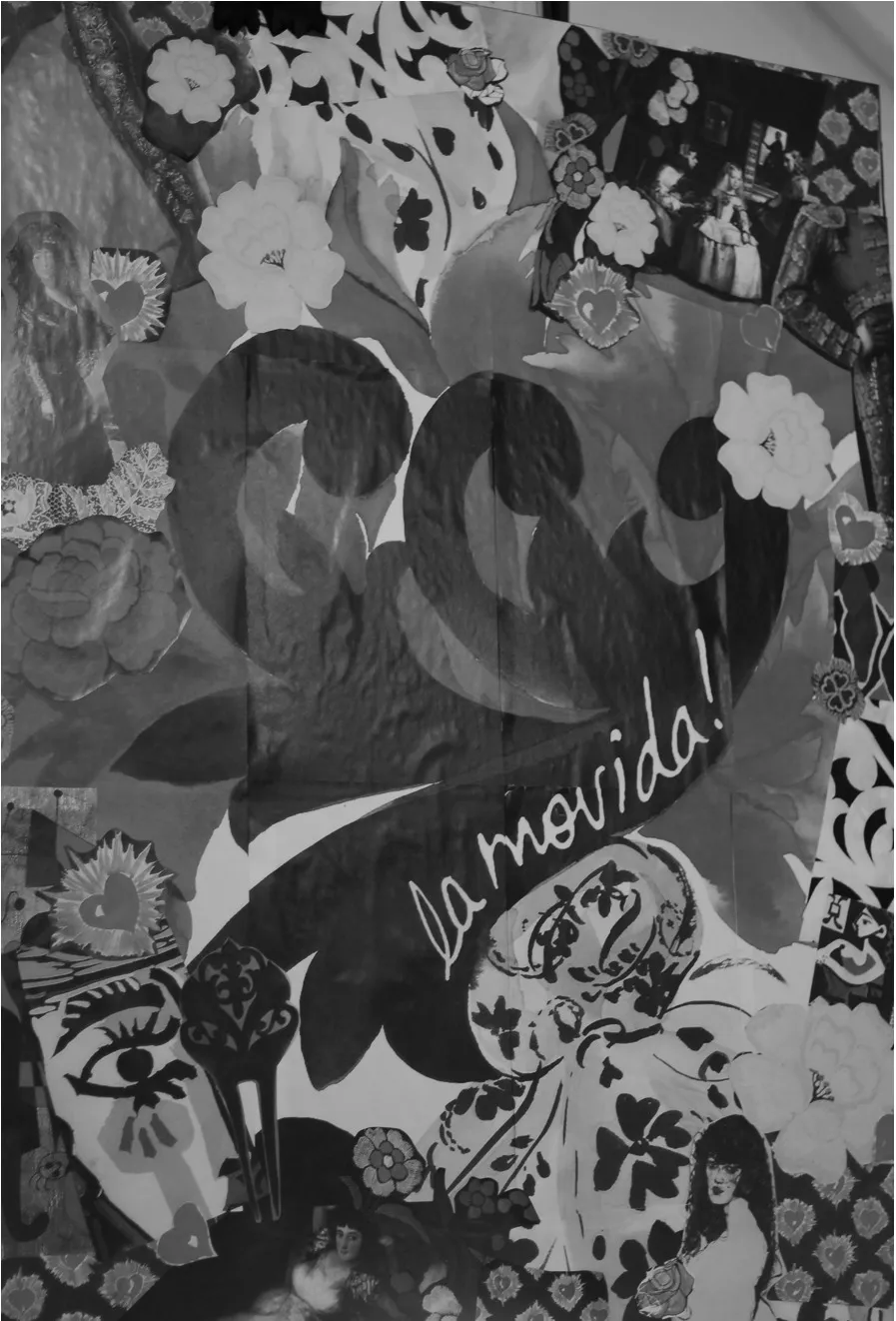

The “inspiration board” for Diane von Furstenberg’s fall 2007 La Movida collection. Photographer: Andrew Bicknell. Courtesy DVF Studio.

The very idea of a cultural economy deserves further explanation. When we think of art and culture, we often think of film or fashion or art or design but often as separate entities. And while they do cultivate their own following, discipline, and norms, they are also part of a far more encompassing and symbiotic whole than we generally consider them. These separate industries operate within a fluid economy that allows creative industries to collaborate with one another, review each other’s products, and offer jobs that cross-fertilize and share skill sets, whether it is an artist who becomes a creative director for a fashion house or a graffiti artist who works for an advertising agency. That there is real importance in the music that designer John Varvatos listens to or what the singer Beyonce wears when she goes out indicates the degree to which those who work in the cultural economy are simultaneously producers and gatekeepers. That the Metropolitan Museum of Art holds the Costume Institute benefit, the annual gala devoted to fashion design, and that Nike hires graffiti artists to design sneakers is evidence of the interdependent nature that artistic and cultural industries have with one another, and their need to be around each other and engaging each other in the same places. And therein lies the significance of New York’s informal social life in cultivating the fluidity of creativity and the symbiotic relationships that fashion, art, music, graphic design, and their related industries have with one another. This type of cross-fertilization is partly responsible for how New York maintains its edge across a wide field of cultural industries. Chapter 6 looks at the various ways that such types of relationships form and produce new types of creativity.

Geography plays an important role, too: all of this occurs in the same limited geography, the island of Manhattan and parts of Brooklyn, Queens, and the Bronx. The parties, the nightlife, the gatekeepers, the artists, and fashion designers and musicians and museums, rock venues, and so on are all sharing the same twenty-five square miles or so. (As are the hoops to jump through, the editors and curators to please, the high-powered jobs, the magazines, music labels, and museums that matter to the global economy.) New York City, due to this dense concentration, is a global tastemaker that dictates the direction of fashion, art, music, and design across the world. So if a creative producer is successful in navigating the networks of New York’s cultural economy, she has, in the process, undoubtedly established herself with the rest of the world.

Astor Place in the East Village. Photographer: Frederick McSwain. © Frederick McSwain. Used by permission.

The mechanisms I’ve discussed so far, and the role of the social, make New York so important to the cultural economy. Part of the cultural economy’s success in New York has to do with the city’s built environment. The close proximity of galleries in Chelsea, nightlife in the Lower East Side, Meatpacking District, and SoHo, and the artistic community that lives in the West Village, Nolita, and Chelsea create a cultural clustering, both within the neighborhood and in the broader “downtown scene”—after all, most of these neighborhoods are just walking distance from one another. Because the social is so important to their careers, creativity, and access to the gatekeepers that review and valorize their work, the ability of artists, designers, and musicians to share the same dense geographic space with gatekeepers in the cultural industries (record labels, fashion houses, museums) makes possible New York’s cultural and artistic economy. The old warehouses left over from industry have made possible the spacious lofts where many designers and artists have studios, galleries, and the like. The “walkability” of New York’s streets and neighborhoods makes run-ins possible between those offering artistic skill sets and those needing them (record labels, advertising firms, etc.). (Contrast this to Los Angeles, a city literally driven by the automobile. These random, street-level interactions would be impossible—laughable, even—in L.A.) New York’s tight-knit nightlife scene, which directs the fashion, music, and art industries toward the hippest, trendiest place to hang out, means that economic functions are almost always happening in social contexts. Put another way, the city’s unique geography and built environment allow for this “perpetual creativity.”Our current understanding of cities and of cultural economies only scratches the surface. By its very nature, creativity is capricious, at times ephemeral, making its value and significance hard to grasp. And yet it also exhibits tendencies and characteristics that, when formalized (as done in this book), give us a deeper understanding of creativity and lessons for how to cultivate and sustain it. What we have to remember is that the seeming randomness of nightlife, of lucky breaks, of exhibitions that make an artist’s career, of the monumental Fashion Week shows that define a designer’s impact exhibit patterns and dynamics in how they became successful (or conversely didn’t). The idea that creative people blindly arrive in New York City just because they were told to, or that cultural industries locate here because that is the historical tendency, completely overlooks the systematic understanding that creative people and firms have about how their economy operates and why they need to be in New York City as opposed to somewhere else—and how they contribute to the fundamental character of the city’s economic success. Creative people don’t just come to New York because of its bohemian mythology. They know creativity happens in New York City and they know why. Social science, as the sociologist Howard Becker once wrote, gives us a greater awareness of things we already know.3 And this bo...