- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

About this book

Winner of the William Sanders Scarborough Prize

"This trenchant work of literary criticism examines the complex ways…African American authors have written about animals. In Bennett's analysis, Richard Wright, Toni Morrison, Jesmyn Ward, and others subvert the racist comparisons that have 'been used against them as a tool of derision and denigration.'...An intense and illuminating reevaluation of black literature and Western thought."

—Ron Charles, Washington Post

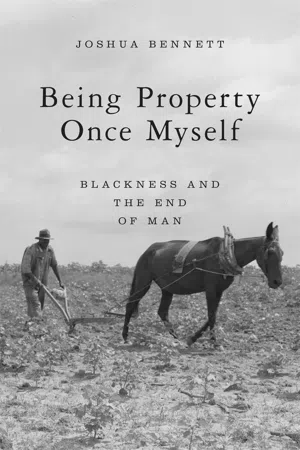

For much of American history, Black people have been conceived and legally defined as nonpersons, a subgenre of the human. In Being Property Once Myself, prize-winning poet Joshua Bennett shows that Blackness has long acted as the caesura between human and nonhuman and delves into the literary imagination and ethical concerns that have emerged from this experience. Each chapter tracks a specific animal—the rat, the cock, the mule, the dog, the shark—in the works of Richard Wright, Toni Morrison, Zora Neale Hurston, Jesmyn Ward, and Robert Hayden. The plantation, the wilderness, the kitchenette overrun with pests, the valuation and sale of animals and enslaved people—all place Black and animal life in fraught proximity.

Bennett suggests that animals are deployed to assert a theory of Black sociality and to combat dominant claims about the limits of personhood. And he turns to the Black radical tradition to challenge the pervasiveness of anti-Blackness in discourses surrounding the environment and animals. Being Property Once Myself is an incisive work of literary criticism and a groundbreaking articulation of undertheorized notions of dehumanization and the Anthropocene.

"A gripping work…Bennett's lyrical lilt in his sharp analyses makes for a thorough yet accessible read."

—LSE Review of Books

"These absorbing, deeply moving pages bring to life a newly reclaimed ethics."

—Colin Dayan, author of The Law Is a White Dog

"Tremendously illuminating…Refreshing and field-defining."

—Salamishah Tillet, author of Sites of Slavery

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

1

Rat

The question is whether such likening of the “other human” ends only in similitude or whether it authorizes, operationalizes, and becomes an ethics toward such labeled humans. In short, what are the material consequences of relegation from human being to vermin being (a pest or nuisance that must be eliminated)? The term pesticide might be innovatively used to encompass not only the substances used to kill pests but also the theory and practice of killing them.… Vermin (the nonhuman) are not only pests to be controlled but also actors that coproduce and impact their would-be controllers.… Since Daniel Headrick’s Tools of Empire and Alfred Crosby’s Ecological Imperialism, studies that follow the itineraries of Europeans and “things European”—technology, science, microbes, and so on—explain what Europeans did but not what these vermin beings “did back.”—Clapperton Chakanetsa Mavhunga, “Vermin Beings: On Pestiferous Animals and Human Game”

I was on my way to a life of bagging tiny mountains,selling poetry on the corners of North Philly,a pest to mothers & Christians.Hearing it too the cop behind me shoved measide for he was an entomologistin a former lifetime & knew the manysong structures of cicadas, bush crickets &fruit flies. He knew the complex courtshipof bark beetles, how the male excavatesa nuptial chamber & buries himself,his back end sticking out till a female sanga lyric of such intensity he squirmed like a Quaker& gave himself over to the quiet historyof trees & ontology. All this he said whilepatting me down, slapping first my ribs, thensliding his palms along the sad, dark shellof my body

Another federal lawsuit filed in 2003 by the Housing Rights Center and 19 tenants accused [former Los Angeles Clippers owner Donald] Sterling of once stating his preference not to rent to Latinos because “Hispanics smoke, drink and just hang around the building.” The lawsuit also accused him of saying “black tenants smell and attract vermin.”—“Clippers Owner Is No Stranger to Race-Related Lawsuits,” Los Angeles Times

The Oxford English Dictionary defines a pest as: “Any thing or person that is noxious, destructive or troublesome.” A variety of other definitions exist in the biological literature, as for example: “a living organism which causes damage or illness to Man or his possessions or is otherwise in some sense, ‘unwanted,’ ” … but most biological definitions include some consideration of the economic significance of the damage caused. Thus “A pest is an organism which harms Man or his property or is likely to do so. The harm must be significant, the damage of economic importance.” … This last distinction is I feel an important one: much time and effort has been devoted in the past to the control of animal populations whose activities, while doubtless of considerable nuisance value were perhaps, if the situation were viewed more objectively, of no real economic significance. In such situations costs of control quite frequently exceed the real costs of any damage caused.2

Pets largely do not provide a service in the household but rather fulfill aesthetic and emotional needs for their masters. (The benefit to the pet is arguable.) Cats and dogs that serve as mousers and ratters sometimes blur this distinction, but more often a household in which animals are kept for these purposes will also include house pets not used for labor. The services provided by mousers and ratters connect them in the minds of their nominal owners to the feral origin of their species, and the killing of vermin causes them to be perceived as unsanitary. They are excluded from the domestic sphere as “outside dogs” or “barn cats,” though sporting dogs used for hunting can be exceptions to this rule.3

The landlord told Raymond’s mother that twelve dollarswould be deducted from the rent for every rat killed.She sends her son to the store for a loaf of Wonder Breadand five pounds of ground beef. Young Raymondreturns with bread & meat that she tears & mixes insidea metal bowl. Mama seasons the meatloaf with rat poisonpulled from the cabinet beneath the sink. Well done,meat sits steaming in the middle of the kitchen floor.Then the scratching scurries. The squeaking beginsand screeches toward the bowl.Raymond describes the wave of rats like a tidal crashcovering the bow, leaping over each other’s bodiesthen the dropping, the stutter kicks.A chorus of rat screams ramble through Raymond’s ears.Keening, furry bodies tense paws against churning gutsas they hit cracked linoleum until an hour passes.Silence swept away the din in death’s footsteps.The mother’s voice quivers in her next request.Raymond, help me count them.4

They waded through these small deaths with rubber gloves,listened to the hump of ea...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Introduction: Horse

- 1. Rat

- 2. Cock

- 3. Mule

- 4. Dog

- 5. Shark

- Notes

- Acknowledgments

- Index