1

Introduction

THE PROMISE OF MAKING

Promises … point us somewhere, which is the where from which we expect so much.… The promise is also an expression of desire; for something to be promising is an indication of something favorable to come.

—SARA AHMED, THE PROMISE OF HAPPINESS, PP. 29–30

What is a prototype? The term prototype is typically used in the context of industrial production, design, and engineering; a prototype is built to model or test demand (from investors or users) for an idea or a product. But can we speak of prototyping a city, a region, a nation, or new ways of being? What would these complex prototypes look like, and what would they do? This book tells the story of how prototyping at vast scales came to be viewed as a promising way to intervene in entrenched structures of inequality, exploitation, and injustice—and how this promise became a demand for individual self-upgrade and economic development. As an ethnographer, I spent ten years (2008–2018) following the people who came together around the idea that cities, regions, economies, and even nations and life itself can be prototyped. They argued that if the production of technology was made available to everyone, concrete alternatives to corporatized, exploitative, and politicized technology could be tested. They envisioned that if people became makers of technology, they would own the things they made and could decide for themselves what their technologies—and by extension their social, economic, and political lives—would be like. The prototypes of intervention they made came to be widely known as the “maker movement.”

This promise of making—that every individual can prototype and thus intervene at scale—was fundamentally exhilarating. It felt empowering to many, like a moral form of hacking; an ethical, democratized technological resistance that was experimenting with how technology can be otherwise. This book unpacks in ethnographic and historical detail how this happened; how “making” became saturated with an affect of intervention—a feeling of agency and control, a sense that alternatives to dominant structures at various spatial and temporal scales were possible. This affect of intervention created seemingly shared visions for the future—even when those visions were incompatible and contradictory. Making was taken up simultaneously to articulate a return to “made in America”—as former US president Barack Obama had envisioned it in 2013—and to overcome “made in China” and its associations of China with backwardness, low quality, and fakery. It was taken up by people, institutions, and corporations that we would typically think of as holding sharply opposing views; feminist technology researchers and designers, venture capitalists, educators, major tech corporations from Intel to Tencent, designers, technology activists, major governments with opposing political views, critical scholars of science and technology. The uptake of making was driven simultaneously by desires to relive modernist ideals of technological progress and by projects aimed at relocating future making and decolonizing technology and design. It was articulated both in terms of a nostalgic longing for older, “better” times and as a toolkit to imagine alternative futures. It became a site to re-articulate the importance of craftsmanship and its associations with individual self-transformation and autonomy. At the same time, it became a resource to envision an alternative designer, engineer, and computing subjectivity that challenged ideals of the autonomous self. The interesting question is not which version is true, but how it was possible for making to be understood through such contradictory terms.

I use the prototype as both an analytical concept and an emic term, i.e., as practiced in technology production and design. As anthropologist Lucy Suchman and colleagues note, the prototype has “particular performative characteristics within the work of new technology design.”1 It is a material and concrete proposal of alternative ways of thinking about technology and its role in the world, not “simply as a matter of talk, but as a means for trying the proposal out.” In other words, the affective qualities of the prototype lie in its simultaneous functioning as object (a model) and process (testing). The term refers to both the normative modeling—the making concrete, or realizing—of specific ideas and the making of an alternative, which carries the potential for contestation and intervention. One of the key promises of the maker movement was that prototyping—the testing and modeling of a technological alternative—was no longer reserved for elites, for scientists, designers, or engineers. Rather, the techniques of “making” from reverse engineering closed systems to building your own devices and machines with open source hardware platforms and tools would make prototyping (and thus the testing and modeling of alternatives) available to everyone. A flurry of maker and open source hardware prototypes made this promise of making concrete; the “DIY cellphone” showed that you—rather than a big corporate player like Apple—can control the design and inner workings of your communication devices;2 the hacking of proprietary health devices demonstrated how you can regain ownership of your body’s data;3 open source 3D printers made palpable how you can mass-produce in your own home.4 All of these projects functioned as prototypes of intervention. They “demo-ed” how to see oneself as capable of intervening in technological ownership, industrial production, economies of scale, broken healthcare systems, and of undoing established notions of the good life. They modeled how to see oneself as in control of what technologies—and by extension one’s social, economic, and political life—could look like. They created a feeling of being able to intervene at scale, from the individual body to the nation.

I use the prototype as an analytical concept to attend to a broadening disillusionment with digital technology and the IT industry. This book shows that ideals and practices of making spread in the very moment as the political and economic regime of techno-solutionism, i.e., the construal of complex social and economic inequities as problems that can be solved by technological solutions, began to be more widely critiqued. Making became more prominent during a time when people began reckoning with the tech industry’s complicity in enabling structures and processes of exploitation, racism, sexism, and exclusion. It was a moment of realization that the structures and processes of capitalism had never been “external” to or “above” the workings of technology and design. The historical condition that gave rise to making was marked by a coming to terms with how technology had enabled the entrenchment of what is commonly thought of as key characteristics of neoliberal capitalism: the economization of the environment, of natural resources, and of life itself in the name of progress and development; the demand placed on individuals to self-actualize as economic agents made responsible for their own survival; the displacement of people and animals in the name of national sovereignty, global competitiveness, and security.

Making’s particular local and translocal formations unfolded through a growing distrust of some of the basic assumptions of modernity itself. It emerged through and alongside a (belated) realization by members of tech and design industries and research that the promise of modern, technological progress and techno-solutionism had occluded and thus legitimized the violence and loss caused by capital accumulation and economic development. Advocates of making were less interested in finding a technological fix than in redefining what technology or a technological solution meant in the first place. They were invested in experimenting with alternative ways of conceiving of and producing technology, which ultimately recuperated the promise of happiness5 and the good life attached to technological progress, precisely as people realized that these feelings had, in fact, long been unattainable for most.6 Making, in other words, was simultaneously an expression and refutation of technological promise.

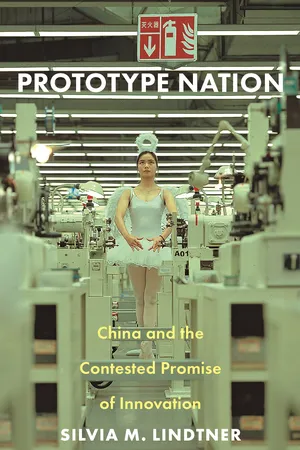

To make sense of this seeming contradiction, this book offers a genealogical approach that attends to the displacements of technological promise. It examines how technological promise can coexist with the proliferating distrust of its attainability. I show that the endurance of technological promise works through its displacement to sites formerly conceived of as the tech periphery, once portrayed as incapable of innovating and “in need” of technological intervention and economic development. Specifically, my focus is on China and how its image began shifting in the broader tech imagination at the very moment that the promise of making took shape and modernist ideals of technological progress were more broadly challenged.7 I show how China, and more specifically the city of Shenzhen in China’s Southeastern province of Guangdong, alongside other regions—including regions in the postcolonies, regions in rural America, former manufacturing cities in Europe and the United States—were rearticulated by a range of actors in the global tech industry, investment, policy, and politics as places where the future was now made, as newly innovative exactly because they were considered to be backward and thus not tainted by capitalism or modernity the same way.8 These displacements of technological promise co-produced China as a prototype nation.

By prototype nation, I mean the stipulation that a nation can function as a prototype—a nation that can serve as the raw material for a new model (for instance, an alternative to established models of modern progress) or can generate demand for a particular kind of future (for instance, a nation’s future freed from past and ongoing colonialism). The idea that a region, even at the scale of the nation, can function as a prototype, as a means of modeling a new way of life for others, and as an archetype that makes certain futures felt, concrete, and “masters the unknowable,” is of course not new; it is historically constituted through projects of modernization, economic development, and colonization.9 The European invention of the “nation-state,” the historian Arif Dirlik reminds us, “was the ultimate vehicle of modernity.”10 The European nation was positioned as the prototype of modern progress and economic development, positing Europe as the archetype and “first” that had let go of feudal pasts and traditions. Other regions were construed as stuck in the past and as “in need” to learn from the Western “model” nations. Postcolonial studies have shown in great depth how the making of the Western nation as the prototype of modernization and development was contingent on the invention of “the Third World” as “other”—the discursive construct of a less civilized “other” that legitimized the extraction of resources the West needed for its own project of progress and economic development.11

The colonial project of prototyping a certain way of life (and demanding that others model themselves after that particular image) endures through the ideals and practices of technology innovation. It lives on in the construal of Silicon Valley’s methods, instruments, and ideas of technology design and engineering as universally applicable.12 And it is sustained through projects aimed at replicating Silicon Valley’s “regional advantage”13 elsewhere—from efforts to build the Silicon Valley of Russia in Skolkovo, a suburb of Moscow, to claims of the emergence of a global creative class.14 It is most recently reactivated through the displacement of technological promise and the stipulation that “regional advantage” is now located elsewhere (in China, in rural America, in sub-Saharan Africa, etc.), at new frontiers, producing new horizons of possibility and investment opportunities—it is these displacements of technological promise that centrally concern this book.

I offer displacements of technological promise to bring into focus the violence and loss that are produced and yet often occluded by the endurance of technological dreams of future making. Weaving together sensibilities from feminist anthropology, critical race studies, and science and technology studies, this ethnography shows that the displacement of technological promise onto what was once imagined as the periphery of technological future making is a discursive move with material consequences, providing legitimacy for the reordering and restructuring of space and people, the flow of investments into certain spaces and technology practices rather than others, the casting of certain people as deserving while continuously keeping others on hold, framed as not (quite) ready, not capable of their own self-investment. Displacements of technological promise are not a linear movement of technological ideals and objects from “here” (the so-called developed world) to “there” (the so-called other part of the world). As I will show in this book, they unfold, instead, through circular, recursive moves, the recuperation of certain pasts and the silencing of others. They require labor and active maintenance. They thrive on the inclusion and exclusion of select sites and bodies. Displacement, anthropologist Juno Salazar Parreñas theorizes, is the “slow violence” that “works over multiple scales and beyond the clean boundaries of specific events, places, and bodies affected.”15 The displacements of technological promise I document in this book are not the same and yet are not unlike the slow violence Parreñas observes as materially experienced through eviction, mega-dam construction, and natural resource ext...