eBook - ePub

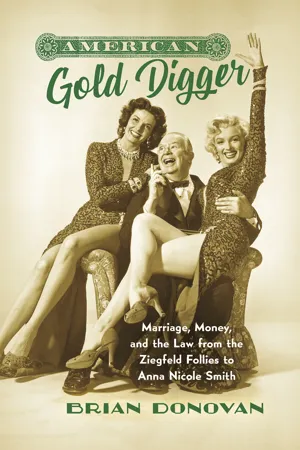

American Gold Digger

Marriage, Money, and the Law from the Ziegfeld Follies to Anna Nicole Smith

- 288 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

American Gold Digger

Marriage, Money, and the Law from the Ziegfeld Follies to Anna Nicole Smith

About this book

The stereotype of the “gold digger” has had a fascinating trajectory in twentieth-century America, from tales of greedy flapper-era chorus girls to tabloid coverage of Anna Nicole Smith and her octogenarian tycoon husband. The term entered American vernacular in the 1910s as women began to assert greater power over courtship, marriage, and finances, threatening men’s control of legal and economic structures. Over the course of the century, the gold digger stereotype reappeared as women pressed for further control over love, sex, and money while laws failed to keep pace with such realignments. The gold digger can be seen in silent films, vaudeville jokes, hip hop lyrics, and reality television. Whether feared, admired, or desired, the figure of the gold digger appears almost everywhere gender, sexuality, class, and race collide.

This fascinating interdisciplinary work reveals the assumptions and disputes around women’s sexual agency in American life, shedding new light on the cultural and legal forces underpinning romantic, sexual, and marital relationships.

This fascinating interdisciplinary work reveals the assumptions and disputes around women’s sexual agency in American life, shedding new light on the cultural and legal forces underpinning romantic, sexual, and marital relationships.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access American Gold Digger by Brian Donovan in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Social History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 The Alimony Panic

The front page of the Washington Post for June 4, 1924, cataloged a number of globally important events. A Hungarian anarchist was charged with plotting to kill King George and the President of France. A resurgent Ku Klux Klan posed problems for the upcoming Democratic National Convention. Two wealthy University of Chicago students, Nathan Leopold and Richard Loeb, faced the death penalty for the premeditated killing of a fourteen-year-old boy. And Peggy Hopkins Joyce, former Ziegfeld Follies star, entered her fourth marriage. News about Joyce’s latest marriage, which shared prominent space with reports of regicide, child murder, and the Klan, fascinated millions of Americans in the 1920s.1

Peggy Hopkins Joyce, also known as Peggy Joyce, was best known as a gold digger, if not the gold digger of the early twentieth century. Constance Rosenblum, in her 2000 biography of Joyce, observed, “From the early twenties into the thirties, the name Peggy Hopkins Joyce resonated mightily in the culture.”2 The story of Peggy Hopkins Joyce—her rise in vaudeville, her stardom as a Ziegfeld Follies Girl, and her tempestuous divorce from Stanley Joyce in 1921—found an audience of millions in newspapers, magazines, and tabloids. Peggy Hopkins Joyce’s glamorous image, promoted in the press and nurtured by her conscious efforts at celebrity, embodied the gold digger at a moment in American cultural history when that image had wide social salience.3 Rosenblum contends that “the phrase gold digger first attached itself to her” during Joyce’s days as a Ziegfeld Follies star.4 The timing of Joyce’s growing notoriety was superb; Americans gained increasing familiarity with the gold digger character type on stage and screen during the years when Joyce’s reputation peaked.5

Peggy Joyce’s public image as a sexually adventurous gold digger eclipsed her acclaim as an actress or stage performer. A feature in Life magazine from 1950 listed Peggy Hopkins Joyce, along with Margaret Sanger, Mary Pickford, and several others, as one of the women who influenced the first half of the twentieth century. Despite placing her with esteemed company, the article described Joyce as “an ostentatious Ziegfeld Girl who became famous mainly for marrying millionaires.” Marian Spritzer’s 1969 Broadway memoir described Peggy as a “pre-Harlow bombshell,” but said “she had acquired more public recognition for her skill at collecting millionaire husbands (and for her off-stage exploits) than for any conspicuous acting ability.” Kevin Brownlow, in his landmark 1976 study of silent film, simply noted, “Peggy Hopkins Joyce was the subject of numerous scandal stories.” Joyce’s primary identity as a gold digger has carried over into the twenty-first century. Robert Hudovernik, in his 2006 photographic collection of Ziegfeld Girls, included a photograph of Joyce shot with her back to the camera and her face turned to its profile, looking away from her naked shoulder, draped in pearls. The accompanying caption read: “Ziegfeld girl Peggy Hopkins Joyce, ca. 1924–27, gold digger.” Supporting its basic identification of her as a gold digger, the caption described Peggy as “wild and unbridled. Her professional career was men.”6 Depictions of Joyce from the early twentieth century to the early twenty-first century portrayed her deviant reputation as a product of her outrageous conduct; Peggy Hopkins Joyce was a gold digger because she exploited men. Outside of the circular logic of “being famous for being famous,” from where did Peggy Hopkins Joyce’s celebrity originate? While not discounting Joyce’s agency, and Joyce’s active role in creating a notorious public persona, she attained iconicity as a gold digger in the context of a widespread panic about men paying unfair alimony to ex-wives. Actions in the legal realm bolstered her notoriety while, at the same time, the scandals surrounding Joyce were used as a justification to reform alimony.

Love, Marriage, and Alimony in the Early Twentieth Century

Alimony is court-mandated financial support paid from one party to another following a couple’s divorce. In the early twentieth century, all but four states had procedures by which individuals could seek alimony.7 In the vast majority of cases, alimony entailed an ex-husband paying toward the maintenance of an ex-wife.8 Alimony was an important part of family law throughout the twentieth century because it was often the only way to protect women from the economic consequences of divorce. The need for alimony reflected the unequal access men and women had to property and income and, therefore, controversies about alimony encompassed competing perspectives about gender roles and the functions of marriage.

During the nineteenth century, marriage was governed by the legal doctrine of coverture. The husband’s authority “covered” a woman’s right to own property, earn an income, or use the legal system. Therefore, husband and wife were a single entity under the law, and the law of coverture created a relationship of dependency of the wife on the husband.9 In the years before states’ Married Women’s Property Acts overturned the legal grip of coverture, when married women could not legally own property, alimony settlements were relatively uncontroversial because they kept a divorced woman from becoming a public charge. As women’s political and economic opportunities expanded during the first two decades of the twentieth century, critics in various professional domains questioned the fairness of the alimony system. Concerns about alimony in the United States reached a crescendo in the late 1920s in the wake of public scandals surrounding Peggy Hopkins Joyce and other alleged gold diggers. Several states considered alimony reforms to cap the money owed to former wives, limit the length of alimony payments, or make it easier for men to receive alimony. Judges publicly criticized alimony seekers as “parasites,” and anti-alimony organizations like the Alimony Payer’s Protective Association boasted of thousands of members. Alimony was portrayed in courtrooms, newspapers, and religious sermons as a crisis that threatened to destroy American families and the U.S. social structure. Yet, the public outcry against alimony was, like awards for alimony themselves, anomalous. The rate of alimony payments remained steady throughout the 1920s. In the 2000s, Constance Shehan and her coauthors noted, “In relative terms, alimony awards are currently—and have historically been—rare in the United States.” Alimony judgments were not only rare but, when they did occur, were typically granted to women who were unable to work and had children to support.10 The moral panic about alimony in the 1920s grew from vast changes that were occurring in American families in the early twentieth century.

Beginning in the late nineteenth century, large-scale industrialization and urbanization changed the economic basis of family life.11 Americans had big families in the nineteenth century as an economic strategy, but the average family size plummeted over the course of the nineteenth century. In 1800, the typical married couple had over seven children per household, which fell to an average of four children per household by the end of the century. Preindustrial labor was divided and managed within families, and the rise of the factory system undermined the place of the family as a singular economic unit. Raising many children no longer held an economic advantage. Breakthroughs in science, medicine, and public health decreased infant mortality and reduced the need for families to have several children in order for a few to survive. By the end of the nineteenth century, these changes altered the economic place of offspring in family life, and a sentimental understanding of children and domesticity accompanied a decline in the size of the average family.12

Changes in family structure during the first two decades of the twentieth century accompanied new employment opportunities for young adults. Young unmarried working-class women, including many immigrants or the daughters of immigrant parents, heavily populated the female labor force. The rapid growth of corporations and retail markets created sales and clerical positions for women. Women filled a rising demand for saleswomen, clerks, and stenographers, and many were hired into jobs that had been the exclusive domain of working-class men. In 1890, there were 3.6 million women in the paid labor force, representing about 19 percent of the female population. By 1910, almost a quarter of the U.S. female population worked outside the home. In Manhattan and Brooklyn, for example, the total number of all working women nearly doubled between 1880 and 1900. Income from rising employment opportunities gave working-class women a growing public presence in cities, and the arrival of mobile and uprooted populations of immigrants and wage-earning women generated innovative ideas about companionship, romance, marriage, dating, sex, and childrearing.13

Several social factors, including the birth control movement, women’s suffrage, a significant rise in women’s employment opportunities, and an expanding leisure industry, generated new expectations about the purpose of marriage and family in the early twentieth century. The idea of a personal lifestyle independent from religious, civic, and family obligations competed with the last vestiges of Victorian asceticism, and marriage came to mean something different in this context. Historian Christina Simmons notes, “The older concept of marriage as a sacred and permanent economic and procreative institution, with political, class, and moral functions, that was grounded in larger networks of kin and community, became less salient.” Historian William Kuby states how, “Gradually the economic model of mate selection faded from view.” Victorianism eroded, and Americans across different classes, and across different ethnic and racial groups, increasingly saw marriage as a place for two people to find personal fulfillment. Experimentation with marriage flourished. New modes of marriage, including the growing prominence of “flapper marriage,” African American “partnership marriage,” feminist marriage, and trial marriage changed the prevailing understanding of traditional matrimony.14

Ideas about marriage that were considered radical in the 1910s were being quickly adopted by men and women from different social strata in the 1920s. Chief among the new frameworks for understanding the functions of matrimony was “companionate marriage.” The term companionate marriage was coined by Barnard history professor Melvin M. Knight in 1924 to describe a marriage based around love and intimacy instead of procreation. Colorado judge Benjamin Barr Lindsey’s 1927 book Companionate Marriage popularized the concept. Companionate marriage emphasized camaraderie, mutual respect, and equality. According to its advocates, companionate marriage entailed having fewer children, adopting a democratic organization for the family, and focusing on the emotional needs of husband and wife. As the companionate marriage ideal grew in the early twentieth century, critics expressed qualms about the use of matrimonial bureaus and matchmaking services. Like concerns about gold diggers, critics of commercialized matchmaking services argued that they corrupted the institution of marriage by encouraging people to leap up the social class ladder by marrying wealthy partners. According to Kuby, marriage services were seen as “a major culprit in the ongoing marriage crisis.”15

Changing marital norms in the United States caused an increase in the divorce rate and a growing perception that American marriages were in a state of crisis. Historian Elaine Tyler May—who studied case files of Southern California divorces that took place from 1880 to 1930—found many 1880s divorce cases triggered by the husband’s or wife’s failure to attain the Victorian ideal of femininity or manliness. Many 1880s divorces stemmed from a husband’s intemperance or a wife’s failure to be “ladylike,” but these grounds for divorce were much rarer by 1920. Divorces in the 1920s were often sparked by the inability of the husband or wife to live up to the modern lifestyle expectations of his or her marriage partner. According to May, increasing numbers of Americans sought the glamor displayed in movie houses, but “day-to-day married life did not meet the promises of the Hollywood style.” The disjunction between the norms of traditional marriage and the desires created by the burgeoning consumer culture generated domestic dissatisfaction across gender, race, and class lines.16

Divorce became a prominent social issue in the 1920s.17 In 1900, there were over 55,000 divorces in the United States, a rate of four divorces per 1,000 residents. In 1910, the number of divorces increased to over 83,000 but the divorce rate remained relatively stable (4.5 divorces per 1,000 people). The decade between 1910 and 1920, however, witnessed a steep rise in the divorce rate. The number of divorces more than doubled during these years, and the divorce rate increased from 4.5 to 7.7 divorces per 1,000 residents.18 Changing patterns of family life, women’s increased participation in the paid labor force, and new forms of leisure and consumption lowered the social stigma of divorce. A 1920 Los Angeles Times editorial ventured, “If one is to judge by the number of sensational divorce suits that are treading on one another’s heels and clogging the calendars of the Superior courts, the country has suddenly been inundated by a tidal wave of marital infidelity.”19 Some members of the white middle and upper classes reacted with outsized outrage to shifting marital norms. As the birthrate among so-called native-born whites declined, prominent whites like Theodore Roosevelt trumpeted fears of “race suicide.” Historian Kristin Celello observes that “race suicide” rhetoric, “when paired with anxieties about the divorce rate, contributed to a full-fledged sense of crisis in regard to the state of family life in the United States.”20

The rising number of divorces, coupled with new lifestyle-based justifications for separation, appeared as signs of vast moral decay for m...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Series Page

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction: The American Gold Digger

- 1. The Alimony Panic

- 2. The Crusade against Heart Balm

- 3. Gold Diggers and Midcentury Domesticity

- 4. Gold Diggers of the Sexual Revolution

- 5. Material Girls

- Epilogue

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index