eBook - ePub

Painted Pomegranates and Needlepoint Rabbis

How Jews Craft Resilience and Create Community

- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Painted Pomegranates and Needlepoint Rabbis

How Jews Craft Resilience and Create Community

About this book

Exploring a contemporary Judaism rich with the textures of family, memory, and fellowship, Jodi Eichler-Levine takes readers inside a flourishing American Jewish crafting movement. As she traveled across the country to homes, craft conventions, synagogue knitting circles, and craftivist actions, she joined in the making, asked questions, and contemplated her own family stories. Jewish Americans, many of them women, are creating ritual challah covers and prayer shawls, ink, clay, or wood pieces, and other articles for family, friends, or Jewish charities. But they are doing much more: armed with perhaps only a needle and thread, they are reckoning with Jewish identity in a fragile and dangerous world.

The work of these crafters embodies a vital Judaism that may lie outside traditional notions of Jewishness, but, Eichler-Levine argues, these crafters are as much engaged as any Jews in honoring and nurturing the fortitude, memory, and community of the Jewish people. Craftmaking is nothing less than an act of generative resilience that fosters survival. Whether taking place in such groups as the Pomegranate Guild of Judaic Needlework or the Jewish Hearts for Pittsburgh, or in a home studio, these everyday acts of creativity—yielding a needlepoint rabbi, say, or a handkerchief embroidered with the Hebrew words tikkun olam—are a crucial part what makes a religious life.

The work of these crafters embodies a vital Judaism that may lie outside traditional notions of Jewishness, but, Eichler-Levine argues, these crafters are as much engaged as any Jews in honoring and nurturing the fortitude, memory, and community of the Jewish people. Craftmaking is nothing less than an act of generative resilience that fosters survival. Whether taking place in such groups as the Pomegranate Guild of Judaic Needlework or the Jewish Hearts for Pittsburgh, or in a home studio, these everyday acts of creativity—yielding a needlepoint rabbi, say, or a handkerchief embroidered with the Hebrew words tikkun olam—are a crucial part what makes a religious life.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Painted Pomegranates and Needlepoint Rabbis by Jodi Eichler-Levine in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Teologia e religione & Teologia ebraica. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 : IN THE BEGINNING

Generative Resilience and the Creation of Gender

In the beginning, there was a handkerchief. It is October 2016. I am in a sunny, white-walled studio talking with Heather Arak-Kanofsky, a professionally trained artist who now has a thriving business creating customized gifts for corporate and private events. Heather—who, like me, is a late Gen Xer—is reflecting on how art and creativity connect with her sense of meaning in the world. “I’ve always thought, ‘Why be an artist? Is it really important to be an artist? Does it really make a difference?’ But if you look all the way back, people needed those things. They wanted to create beauty, they needed to have that in their lives. And I feel like for me, the idea of something being transformed from profane to sacred. …” Excited, she interrupts herself to get an object from one of the low bookshelves that line the sides of the room. It is a white handkerchief covered with colorful embroidery, laid out on a red book cover (fig. 1.1). Then she tells me the story of the piece:

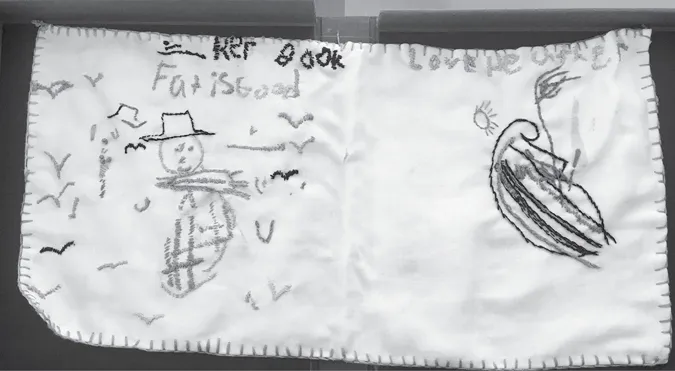

I had this fight with my grandma when I was six years old. I think it was when my sister was being born … and I didn’t wanna get out of my nightgown. I like being in my PJs all day. It’s comfortable. And so she was like, “Get up, you need to get up.” And I said something, and then I said, “You’re fat.” We were having an argument. “You’re fat.” And she said, “Wow, that was very hurtful.” So I felt really bad … you know, I loved her so much. … So I said, “I need a handkerchief,” and she said, “Okay.” So she gave me the handkerchief and I drew this for her, and then she embroidered it.1

FIGURE 1.1. Heather Arak-Kanofsky and Muriel Kamins Lefkowitz, embroidered handkerchief. Photograph by the author.

I am awed by the care with which this item has been preserved, and by the way in which she framed its story. For Heather, the handkerchief was the site of transforming the profane into the sacred. The aesthetic style here is homey and collaborative. On the left-hand side is a person—a person who looks a bit like a snowman—wearing a hat and scarf. On the right-hand side, her grandmother, pictured in profile, is an amalgamation of abstract curves and lines, filled in with browns and blacks and greens, with hints of orange and a delicate, tiny sun. Arak-Kanofsky’s grandmother used pink embroidery floss to stitch over the carefully lettered phrase “Fat is Good” on the left and “Love Heather” on the right; a similar mauve shade was used in a blanket stitch all around the border. The air around us feels still, its quietness almost palpable, as we contemplate this heirloom.

Arak-Kanofsky describes how her grandmother kept the piece for years, using it as a book cover, then gave it back to her when she became engaged. In turn, on her wedding day—which was also her grandmother’s wedding anniversary—she had the piece mounted and gave it back to her, once more, as a gift. Eventually, after her grandmother’s death, she inherited it. Now it is one of the many carefully curated objects that reside in her airy workspace, a memento. She sums up some of what she learned from the experience. In part, it showed her that family was a place where you could push limits, where a moment of discomfort was transformed into something different through the meaning making process of family life. Here, “fat” was turned from a pejorative term into a valued descriptor. Ultimately, she says, it taught her this: “You can take a terrible moment and make it into something that is really amazing.”2

You could say that the practice of religion is frequently about taking a terrible moment and make it into something that is really amazing—or, at the very least, into something that is abundant in meaning. Many Jewish holidays, such as Purim and Passover, commemorate moments of persecution and transform them into days of feasting and revelry. The handkerchief does this, too, in a way that is less obviously Jewish than a Passover seder and yet no less vital for how Jewish Americans make profound religious meaning in their lives. It is an everyday Judaism of feeling. It tinkers with meaning in a way that is similar to the move made in midrash, Jewish traditions of interpretation. A six-year-old remade the world in crayons, and her grandmother added the next stratum in thread, like the layered deliberations of rabbinic thought. The word “fat”—a pejorative, painful term for modern American women—became re-rendered as a sign of capacious love and intergenerational bonding via an iterative creative process.3 In this handkerchief form, the portraiture created by a child—an ephemeral practice that, in many homes, is relegated to recycling bins across the continent, ad infinitum, each day—is inscribed as a permanent keepsake instead. The grandmother’s bulky body is refigured by the hand of the child who descended from the child who descended through those hips. It is seen anew as a beautiful one. The bond built by the handkerchief was so important to Heather that the handkerchief itself became a part of her life-cycle rituals. The item is also materially lasting, lingering here in the studio long after the grandmother’s death. What is this act, if not a religious one?

In this object and its attendant story, we see the myriad processes we will encounter throughout this book: the transmission of affect, technological mediation, the promotion of gift culture, the bonds of community, a moment of repair, and the hold of memory. It speaks of a kind of activism, too, a body positivity that is hard won but enduring. The “Fat is Good” handkerchief encapsulates generative resilience, the process of struggle, adaptation, and intimate production that I have found so frequently in the diverse stories contained herein. To generate resilience is to perform an existential act of survival. To create any item at all is a profound act of strength, perhaps even chutzpah, in a world that has always been falling a little bit apart at the seams.

In psychological literature, resilience denotes both processes and capacities of positive adaptation in the face of stressors and adversities.4 In the field of religious studies, resilience often indicates survival and the ability to endure.5 In the stories that make up this book, acts of creation constitute resilient actions that are, in their way, religious, particularly when we focus on religion as a social process. That is to say, they help their creators to “make homes” and “confront suffering,” and for some of my interlocutors, they also buttress “a network of relationships between heaven and earth involving humans of all ages and many different sacred figures together.”6 Even when these actions don’t engage directly with formal rituals or institutions, they intersect with the broad category we call religion on multiple subtle frequencies. This does not happen in a systematic way. In fact, the value of approaching these objects and moments as examples of religion—and Judaism—comes because they form a loose network, not a neat arrangement. Religion, like the yarn at the bottom of my knitting bag, is a messy tangle of feelings, relationships, and attunements, shot through with taut fibers of tradition.

The “Fat is Good” handkerchief also asks that we think about gender. This is not just because it is about women’s bodies—all human beings live in bodies of varying sexes, and they all “do gender,” performing a wide range of culturally bounded signals that other humans interpret as signs of identity (including not just masculinity and femininity but also a host of other possibilities, including nonbinary ones).7 These are “intimate engagements”: snapshots of gender and Jewish crafts with a measure of interiority and reflection, but also with a subtle awareness of broader publics and social contexts.8 How crafters discuss acts of creation, parenting, and generations are all deeply enmeshed with the making of gender among Jewish Americans. On the one hand, interpretations of art and craft, as well as women’s religious experiences, sometimes trend toward romanticized ideas about so-called feminine crafts.9 On the other hand, deconstructing that interpretation does an injustice to its power in many lives. In other words, even though it is important to notice such rhetorical patterns, I do not want to notice them out of existence; the traditional gender norms that I want us to understand historically are still meaningful ideas that animate the religious lives of many Jewish Americans. Similarly, the power of creation—so laden with theological overdetermination—is often thought through as emblematic of women’s procreative capabilities. This metaphor has pitfalls for those who literally or figuratively struggle with creation and procreation, production and reproduction. Can we find a way to disentangle and revise our notions of gender, creation, and craft—and, alongside these, our notions of Jewishness and religion?

GENDERING GENERATIVITY

Generativity is gendered. This happens in many ways. There are times when it is gendered as masculine—think of the word “seminal,” from “semen”—times when it is pictured in terms that are feminine—“a pregnant pause”—and other times when the imagery is more complicated. Consider this verse from the Hebrew Bible, Psalm 139:13: “You knit me together in my mother’s womb.”10 This verse addresses a male creator deity who is anthropomorphic, described as performing a skilled craft that takes place within the body of a woman.11 That psalm in full, which emphasizes the intimacy between the deity and the speaker, details the wonders of God’s creation and contains myriad Hebrew synonyms for fashioning, making, and forming, along with a great deal of nature imagery and an emphasis on God’s knowledge of humans’ innermost thoughts. To create is thus associated with divine power, but even in this version, the divine being does not create in a vacuum: the God of this psalm does his work in the depths of female bodies and deep caves, working in concert with embodied and earthly materials, however hidden. In Jewish descriptions of creation, from ancient Canaanite phallic pillars to kabbalistic ideas of the divine phallus emanating into the feminized sefirot (“luminosities,” the ten emanations of divinity), images of male bodies as the givers of life abound.12

Not all notions of reproduction or life-giving creation have a masculine agent. In a variety of cultural contexts, we find examples where the bodies of women were celebrated for their fecundity in ways that might have been religious. Think, for example, of the Venus of Willendorf, a statue found in Austria, dating to the Upper Paleolithic period, which was celebrated by many second-wave feminists—those most active in the 1960s through the 1980s—as an emblem of the maternal divine. (Today, you can also find a lovely pattern online to crochet your very own Venus of Willendorf, and it made the social media rounds as recently as July 2018, so she must still hold some cultural cachet.)13 When modern feminist spirituality movements emerged in the 1960s and 1970s, both women’s bodies and feminized creative processes became foci in metaphorical and literal ways. Jewish feminists reclaimed Lilith, Adam’s legendary first wife who, in various rabbinic tellings, had been exiled before the creation of Eve and characterized as a demoness.14 Some Jewish feminists echoed other second-wave feminists in their attention to fertility images, reviving attention to the ancient Near Eastern fertility goddesses that the male authors of the Hebrew Bible and, later, the rabbinic tradition, had castigated. They celebrated feminist seders and created new theologies, prayer language, and rituals that spoke to a craving for ways of being Jewish women in the context of second-wave feminism, paralleling related developments in other religious communities throughout the United States.15 Many of my informants came of age during this time and carry that language forward with them.

By the 1990s, however, some feminists questioned what it meant to make women’s reproductive capacities so central to their religious identity, or to elide the nuanced history of weaving, knitting, and other trades, which were not always conducted by women, nor were these activities always pleasurable for the women who performed them. As we entered the twenty-first century, unpacking gender as a binary notion also entered more powerfully into this conversation. Many people moved toward thinking about gender as both a social process and a continuum; they noted how sex-gender systems varied across time and space, including the recognition that many cultures have more than two gender identities.16 We have also begun to fathom that biological sex is not a simple either/or but rather an assignment built upon myriad factors.17 My ethnographic data doesn’t always reflect these nuances. In my discussions with crafters, I could not escape a valorization of various arts, especially the needle arts, as women’s work, even as I also sometimes encountered the work of male and gender nonbinary crafters, as well as forms of ritual innovation that trouble gender norms.

In my online survey, conducted in 2016, a few questions prompted respondents to reflect upon whether there were connections between gender and craft in their lives. Some responses reinforce an association between women and creativity:

I feel that I am part of a special heritage of women, and a continuing link in a chain of women creating art. I feel that there is a long tradition of women beautifying practical, everyday items. … On a practical level, I am pretty sure that every craft I know how to do has been taught to me by a woman. I feel that it is a powerful way for women to connect with one another, as teachers, students, and fellow artists. I’m not exactly sure how to explain it, but I often feel that my art expresses my femininity.18

This statement frames crafting as women’s work while also celebrating the importance of the everyday, as Arak-Kanofsky did at the beginning of this chapter. Another respondent wrote: “Sewing and knitting make me feel feminine, in a way, and powerful. It’s a way of combining femininity and empowerment for me. I can CREATE beautiful, meaningful, useful things. It makes me feel like a meaningful, useful woman—more than a wife, more than a mother. It’s a part of my identity as a person.”19 This statement simultaneously celebrates crafting as feminine while also indicating that it is something beyond traditional roles of being a wife or mother.20 For her, craft imbues power, and it is not the power of a heavy-bellied ancient fertility goddess—it is the power of a modern woman who can create “beautiful, meaningful, useful things”: a producer, rather than a consumer.

For Jews, creation and generativity are also special categories in terms of ritual practice and narrative meaning. Productions and reproductions, creations and creativity, are theoretically, theologically, and ritually intertwined. The very notion of resting on the Sabbath is done in imitation of God, the ultimate creator. Understanding Jewish art and craft requires attending deeply to how things are made. Artist and professor Ben Schachter compares these Jewish definitions of “work” with art criticism that attends to “process.” He draws our attention to the melakhot, the thirty-nine categories of work forbidden on the Sabbath that are enumerated in the Talmud. These are then linked with both notions of divine creation and the actions of Bezalel, the chief artisan of the Tabernacle, whose actions are described in the book of Exodus an...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Illustrations

- Prologue: The Needlepoint Rabbi

- Introduction: Suturing the Mortal World

- 1. In the Beginning: Generative Resilience and the Creation of Gender

- 2. Black Fire, White Pixels, and Golden Threads: Technology and Craft

- 3. Threads between People: The Art of the Gift

- 4. Bezalel’s Heirs: Crafting in Community

- 5. Tikkun Olam to the Max: Activism and Resistance

- 6. Generating the Generations: Crafting Memory in a Fragile World

- Conclusion: The Fabric of Forever

- Acknowledgments

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index