![]()

1

GRAPHIC EXCHANGES

Robert Douglass Jr.’s Activism in Philadelphia

Robert Douglass Jr.’s mind raced on his journey from the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in 1834. As he walked the uneven streets of Philadelphia between freedom and slavery, the stinging personal rejection that he had faced just minutes before proved powerful for the young, gifted, free black artist. His spirits must have soared months before when the prestigious museum and school of fine arts accepted his painting Portrait of a Gentleman to be exhibited in the same hallways as some of the greatest European and American master painters and artists.1 Perhaps it was William Lloyd Garrison, the revered and reviled abolitionist, or maybe James Forten, the wealthy black Philadelphian activist, that Douglass recorded with his paintbrush.2 Nevertheless, the occasion was momentous; his painting was the first completed by an African American displayed in those hallowed galleries.3 Yet, as he attempted to visit his exhibited painting, officials prevented him from entering the building. He was a black man who wished to browse its collections with white patrons present.4 Turned away on account of his race and institutionalized racial segregation, Douglass recalled this experience with racial prejudice for several decades in published letters and advertisements as a means of encouraging patronage of his work. Not one to concede defeat, Douglass only became more involved in campaigns to end racial discrimination throughout his life.5

The images created by Robert Douglass Jr. during the 1830s signaled the broad range of antislavery activity facilitated by black men and women. His black-authored images affirmed the dignity of African-descended people in ways that have largely been unexamined by scholars, who have focused their studies primarily on white-authored visual materials.6 Scrutinizing Douglass’s artistic production and its instrumental role in advancing the abolitionist movement reveals the networks of black and white leadership while also providing a fuller view of African American activism during the 1830s. The cultural milieu that shaped, and in turn was shaped by, Douglass through the technologies of print and visual culture contributed to understandings of race and strengthened the wave of antislavery activism during the 1830s. He applied his broad artistic, political, academic, and international education to his profession as a visual artist and created images that challenged black stereotypes by overlaying visual themes of black respectability, dignity, and intellect. He also intended and designed his images to garner support for the antislavery movement. In doing so, Robert Douglass Jr. created images of black people and white abolitionists that challenged flagrantly racist messages presented to nineteenth-century audiences. This work doubled as a cultural weapon with which black artists like Douglass challenged stereotypes of blackness and produced counternarratives in the service of expanding rights for free and enslaved African Americans. As an activist and cultural producer with stakes in the representation of African Americans, Douglass both expanded and refined discourses of race in the antebellum United States. With Douglass exerting control over the means of visual production and racial representation, the struggle for racial equality in the nineteenth century begins to look different.

THE VISUAL LANDSCAPE OF RACE IN THE EARLY REPUBLIC

Posted on public streets, collected for viewing at home, pasted to the ceilings of taverns, and printed in periodicals, images increasingly pervaded the lives of people living in the 1830s. Among these were images that perpetuated ideas of blackness as debased, comical, and inferior. Some of the most widely circulated and visible of these derogatory images appeared in the streets and inside parlors. In Boston, for example, several crudely printed images mocked free black Bostonians’ annual commemoration of the abolition of the international slave trade in 1808. For decades following, these so-called bobalition prints derided African Americans by presenting them with improper speech, cartoonish bodies, and disproportionate clothing.7 These images taught and reinforced racist ideology while worrying some African Americans, such as the Reverend Hosea Easton, who lamented:

Cuts and placards descriptive of the negroe’s deformity, are every where displayed to the observation of the young, with corresponding broken lingo, the very character of which is marked with design. Many of the popular book stores, in commercial towns and cities, have their show-windows lined with them. The barrooms of the most popular public houses in the country, sometimes have their ceiling literally covered with them. This display of American civility is under the daily observation of every class of society, even in New England. But this kind of education is not only systematized, but legalized.8

Such images, “marked with [fabricated and misleading] design,” taught the young and the old alike, regardless of class, that the fanciful exterior characteristics of African Americans revealed their allegedly interior, inferior state of mind. More specifically, they encouraged viewers to believe that African Americans were incapable of social graces, intellectually inept, and unworthy of the rights that white Americans enjoyed. These prints ridiculed African Americans’ annual celebration that one avenue of slavery—the importation of slaves from abroad—had closed. Theirs was a tradition of individual and collective campaigns to secure the right of freedom, and such public displays were lampooned on parade routes and in print.9

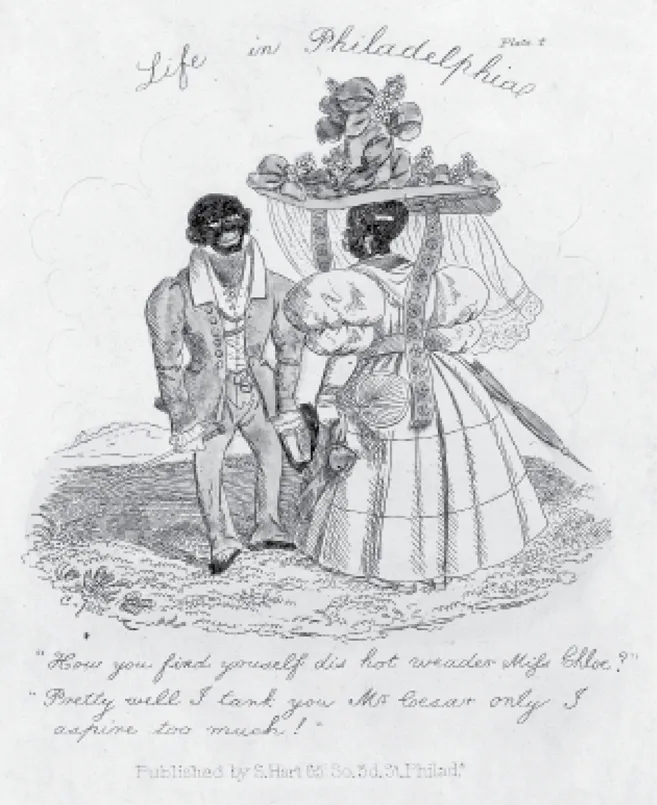

The most popular of these derogatory images found in the home were the Life in Philadelphia prints created by Philadelphia artist Edward Williams Clay between 1828 and 1830 that mocked white Quakers and free black Philadelphians. Influenced by the people he saw in Philadelphia and the racist caricatures he viewed while in Europe, Clay created prints that communicated a cruel dissonance between African Americans’ exterior bourgeois trappings and their interior ability to understand and embody genteel culture. For Clay, these black urbanites merely aspired to, but did not deserve, respect within the United States.10 One of the figures in his prints, Miss Chloe, says as much (fig. 1.1). When asked how she feels in the hot weather, she responds, “Pretty well I tank you Mr. Cesar only I aspire too much!” Riddled with too many bows and flowers, the enormous hat perched precariously on Miss Chloe’s head became an exterior display of her interior mental state. Clay’s use of fragmented syntax, disproportionate bodies, oversized clothing, and other caricatured elements signaled to nineteenth-century viewers that black men and women merited a station in life that was less than that which they desired. In adopting the fineries of respectable society, such as the cane that Mr. Cesar holds and the fan and parasol that Miss Chloe clutches, black men and women, argued Clay, brought derision upon themselves because they wrongly assumed that they could inhabit the genteel society that such accoutrements denoted. Though they might attempt to replicate it, their failures further marked their status as outsiders from respectable genteel culture.11

Figure 1.1. Edward Williams Clay, “How You Find Yourself Dis Hot Weader Miss Chloe?” Life in Philadelphia series, Philadelphia Set, 1830. Courtesy of the Library Company of Philadelphia.

During the 1830s, members of the public commonly understood images to possess the power to shape the minds and transform the sensibilities of their viewers. In a description published in Parley’s Magazine, the benefits of engravings seemed endless. With a self-reported subscription base of twenty thousand customers, the periodical proposed that its pages featured a plethora of images “selected not only with a view to adorn the work, but to improve the taste, cultivate the mind, and raise the affections of the young to appropriate and worthy objects.”12 More specifically, the magazine proposed that its images would transform those who viewed them into “better children, better brothers, better sisters, better pupils, better associates, and, in the end, better citizens.”13 The magazine carefully instructed parents and teachers: “Let children look upon the pictures, not as pictures merely; but let them be taught to study them. What can be more rich in valuable materials for instructive lessons than a good engraving?”14 Didactic and persuasive, images could be instruments to shape young people into improved members of society. The instructive influence of images was not limited to children; the actions of several abolitionist institutions revealed that the ideas communicated by images could arouse strong reactions in adults as well.

Images proved especially provocative to abolitionists and those whom they hoped to convert to their cause. This included the circulation of antislavery images to stalwart defenders of slavery in the South with the hope of persuading them of slavery’s barbarities. Abolitionists wielded images as weapons. They recorded their intentions for antislavery images and the reactions of proslavery supporters in the 1836 Annual Report of the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society. A member of the organization wrote that images functioned differently than did text:

But the pictures! The pictures!! These seem to have been specially offensive. And why, unless it is because they give specially distinct impressions of the horrors of slavery? … Pictorial representations have ever been used with success, in making any desirable impression upon the minds of men, the bulk of whom are more immediately and thoroughly affected by a picture, than a verbal description. Why then should they not be used, in the exposure we purpose to make of our national wickedness? If any of them represent what does not exist, let the falsehood be shown and reproved. But with what reason or justice are we called upon to suppress the picture, so long as the original is allowed to defile our land?15

Abolitionists knew well that the power of images lay in their ability not merely to engage viewers but also to increase the exposure of the ideas that they contained. Operating with the belief that images could “more immediately and thoroughly” influence people than text, the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society attempted to incite abhorrence of slavery with pictures that showed enslaved people suffering violence at the hands of slave owners. The writer indicated that these images reported the truths of slavery and, confident in their veracity, challenged naysayers to “let the falsehood be shown and reproved.” Disproving the ideas conveyed in an image might be more difficult than producing an image that represented contrary views.

Those opposed to abolitionism produced their own images that condemned the idea of abolitionism. One print appearing in Boston around 1833 denounced the “fanaticism” of several antislavery leaders in New York. The foreground depicts three white abolitionists—Arthur Tappan, William Lloyd Garrison, and an unidentified man—who discuss the merits of purchasing linen produced without slave labor as an emancipated slave moves away from the group, dagger in hand, in pursuit of a flying insect labeled “Food.” Directly behind the formerly enslaved man is a scene labeled “Insur[r]ection in St. Domingo! Cruelty, Lust, and blood!” that depicts black people using swords, knives, and an ax to murder white men, women, and children. As the text on the print warns, freeing the enslaved would “drench America in blood” as a result of a feared black massacre of white people in the United States.16 Noting that “several of the principal streets are graced this week with a lithographic caricature of the formation of the New York City Anti-Slavery Society,” the Liberator understood this caricature to have the unintended effect of aiding the cause of the organization: “It is a miserable affair—not worth the description. But miserable as it is, it will do our cause some work.”17 The malicious image, the Liberator implied, baldly revealed the racism of its creator and supporters. Furthermore, the hyperbolic language and alarmist fears that comprised the main thrust of the print’s message cast its author and those who shared his ideas as extremist, overly reactive, and dishonest.

Both derogatory and affirmative images depicting African Americans underscored the belief that images could alter the way that people understood the multiple meanings ascribed to the ideas of blackness and abolitionism. As objects that documented the debates over abolitionism and free black people in the United States, these images reveal how their creators used antebellum visual culture to package and deliver ideas about race to audiences. Scholars have mined white-authored images for information about racial attitudes in the United States and in the process have shown how these sources reveal a wealth of information about the lives of enslaved people.18 Furthermore, scholars have shown how images of African Americans created during the half-century after the American Revolution provide windows into evolving ideas, including colonialism, biological racism, interracial sex, and white superiority.19 Fewer scholars have studied visual materials created by black men and women during the early nineteenth century. Those who have done so argued that African American artists documented the social history of African Americans and employed religious imagery to stress the benefits of abolition and the altruism of Christian teachings.20 Images, in short, became a contested terrain on which numerous stakeholders supported their positions because they knew that viewers invested images with the ability to be persuasive, truthful, and educational. They also understood images to be sources of comedy, satire, and caricature prone to exaggeration, distortions, and falsehoods. When adding the variable of race to the visual equation, the politics of these images became exponentially more complex and sometimes explosive. Few Americans knew this better than those who called Philadelphia home.

BLACK PHILADELPHIA

Douglass’s expulsion from the premises of the Pennsylvania Ac...