- 176 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

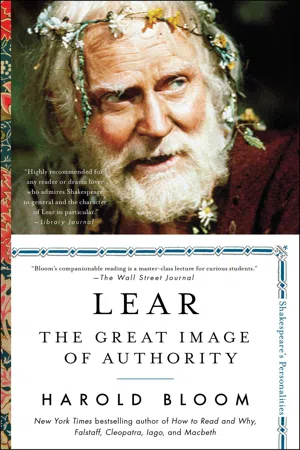

From one of the greatest Shakespeare scholars of our time, a beloved professor who has taught the Bard for over half a century—an intimate, wise, deeply compelling portrait of Lear, arguably Shakespeare’s most tragic and compelling character, the third in a series of five short books hailed as Harold Bloom’s “last love letter to the shaping spirit of his imagination” (The New York Times Book Review).

King Lear is one of the most famous and compelling characters in literature. The aged, abused monarch—a man in his eighties, like Bloom himself—is at once the consummate figure of authority and the classic example of the fall from grace and widely agreed to be Shakespeare’s most moving, tragic hero.

Award-winning writer and beloved professor Harold Bloom writes about Lear with wisdom, joy, exuberance, and compassion. He also explores his own personal relationship to the character: Just as we encounter one Anna Karenina or Jay Gatsby when we are seventeen and another when we are forty, Bloom writes about his shifting understanding—over the course of his own lifetime—of this endlessly compelling figure, so that the book also becomes an extraordinarily moving argument for literature as a path to and a measure of our humanity.

Bloom is mesmerizing in the classroom, wrestling with the often tragic choices Shakespeare’s characters make. Now he brings that insight to his “measured, thoughtful assessment of a key play in the Shakespeare canon” (Kirkus Reviews). “Lear is a “short, superb book that has a depth of observation acquired from a lifetime of study” (Publishers Weekly).

King Lear is one of the most famous and compelling characters in literature. The aged, abused monarch—a man in his eighties, like Bloom himself—is at once the consummate figure of authority and the classic example of the fall from grace and widely agreed to be Shakespeare’s most moving, tragic hero.

Award-winning writer and beloved professor Harold Bloom writes about Lear with wisdom, joy, exuberance, and compassion. He also explores his own personal relationship to the character: Just as we encounter one Anna Karenina or Jay Gatsby when we are seventeen and another when we are forty, Bloom writes about his shifting understanding—over the course of his own lifetime—of this endlessly compelling figure, so that the book also becomes an extraordinarily moving argument for literature as a path to and a measure of our humanity.

Bloom is mesmerizing in the classroom, wrestling with the often tragic choices Shakespeare’s characters make. Now he brings that insight to his “measured, thoughtful assessment of a key play in the Shakespeare canon” (Kirkus Reviews). “Lear is a “short, superb book that has a depth of observation acquired from a lifetime of study” (Publishers Weekly).

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Lear by Harold Bloom in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Literary Criticism in Drama. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

Every Inch a King

Shakespeare’s most challenging personalities are Prince Hamlet and King Lear. The Tragedy of Hamlet Prince of Denmark and The Tragedy of King Lear rival each other as the two ultimate dramas yet conceived by humankind.

Hamlet and Lear have virtually nothing in common. The Prince of Denmark carries intellect and consciousness to their limits. King Lear of Britain lacks self-awareness and any understanding of other selves, yet his capacity for feeling is beyond measure.

The ironies of both personalities are too large to be fully seen. Readers and playgoers have to confront the difficulty of judging what is ironic and what is not. Hamlet’s inwardness is available to us through his seven soliloquies but their interpretation frequently is blocked because no other dramatic protagonist is so adept at not saying what he means or not meaning what he says. Lear incessantly proclaims his anguish, fury, outrage, and grief, and while he means everything he says, we never become accustomed to his amazing range of intense feeling. His violent expressionism desires us to experience his inmost being, but we lack the resources to receive that increasing chaos.

We know almost nothing of Shakespeare’s own inwardness. His beliefs or absence of them cannot be induced from his plays or poems. I find it useless to speculate about his religious orientation. Whether Shakespeare the man was Protestant or recusant Catholic, skeptic or nihilist, I neither know nor care. Hamlet and King Lear both contain biblical references but neither is a “Christian” drama. There is no question of redemption in either play. A Christian work, however tragic, must finally be optimistic.

In King Lear there are only three survivors: Edgar, Albany, Kent. Lear and Gloucester die of inextricably fused joy and grief. The monsters Goneril, Regan, Cornwall, Oswald all die violently. Edmund the Bastard is cut down by his half brother Edgar. The Fool vanishes. Cordelia is murdered. When Lear dies, there are apocalyptic overtones:

Kent: Is this the promised end?

Edgar: Or image of that horror?

Albany: Fall, and cease.

act 5, scene 3, lines 261–62

Those are not the accents of Christian optimism. Shakespeare being Shakespeare, I have not the temerity to suggest precisely what they are. The gods of King Lear are curiously Roman in name though the more or less historical King Leir was supposed to have reigned about the time of the founding of Rome, in the eighth century before the Common Era. That might have made Leir the contemporary of the prophet Elijah, and so alive a century before King Solomon the Wise.

King James I, who was the crucial member of the audience attending Shakespeare’s plays from 1603 until 1613, has been called “the wisest fool in Christendom.” As King he regarded himself as a mortal God and fancied he was the new King Solomon. He is perhaps the only monarch of Britain who was an intellectual of sorts, and he wrote a few mediocre books. His clashes with Parliament over revenues foreshadowed the disaster of his son and successor Charles I, beheaded for high treason in January 1649.

When Lear speaks of the great image of authority, his bitterness bursts forth: “a dog’s obeyed in office.” Yet Kent, the loyal follower whom he has exiled, and who disguises himself so as to go on serving Lear, seeks and finds authority in the great King:

Lear: What art thou?

Kent: A very honest-hearted fellow, and as poor as the King.

Lear: If thou be’st as poor for a subject as he’s for a king, thou art poor enough. What wouldst thou?

Kent: Service.

Lear: Who wouldst thou serve?

Kent: You.

Lear: Dost thou know me, fellow?

Kent: No, sir; but you have that in your countenance which I would fain call master.

Lear: What’s that?

Kent: Authority.

act 1, scene 4, lines 19–30

The ultimate authority in The Tragedie of King Lear ought to be the gods but they seem to be uncaring or equivocal. Edmund the Bastard invokes Nature as his goddess, and urges her to stand up for bastards.

What Edmund means by “nature” is antithetical to what Lear regards as the distinction between “natural” and “unnatural.” Goneril and Regan in their father’s judgment are “unnatural hags.” They see their behavior as “natural,” as does Edmund.

“Nothing” is a term prevalent in this tragedy. There are thirty-four uses of “nothing” and forty-two of “nature,” “natural,” “unnatural.” The relationship between nothing and nature is a vexed one throughout Shakespeare and is particularly anguished in The Tragedie of King Lear. In the Christian argument, God creates nature out of nothingness. The end of nature, according to the Revelation of St. John the Apostle, comes in a return to a restored Eden:

And he showed me a pure river of water of life, clear as crystal, proceeding out of the throne of God, and of the Lamb.

In the midst of the street of it, and of either side of the river was the tree of life, which bare twelve manner of fruits, and gave fruit every month: and the leaves of the tree served to heal the nations with.

Geneva Bible, Revelation 22:1–2

That healing abundance is alien to Lear’s tragedy. As the drama closes, Albany, Kent, and Edgar discover that Lear’s prophecy has been fulfilled: Nothing has come of nothing. There is no revelation; nature again drifts back to chaos.

Authority, as a concept, is neither Hebrew nor Greek. It is Roman. Hannah Arendt defined authority as an augmentation of the foundations. When Julius Caesar usurped all authority, he did it in the name of returning to the founders of Rome. Though an expedient fiction, all subsequent authority, whether secular or spiritual, is Caesarian and extends that seminal usurpation of power.

No one has worked out the intricate relationship between authority and what we have learned to call “personality.” The European Renaissance of Michel Eyquem de Montaigne (1533–1592), Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra (1547–1616), and William Shakespeare (1564–1616) can be said to have inaugurated our sense of personality. Montaigne invents and studies his own personality, Cervantes independently creates the idiosyncratic Don Quixote and the surprisingly witty and sane Sancho Panza, and Shakespeare peoples his heterocosm with myriad people, each with her or his own personality.

Montaigne, skeptical of all prior authority, massively portrays himself with the freedom of a man who begins anew with a tabula rasa of speculation. Cervantes mocks his forerunners and asserts his personal glory that he shares with Don Quixote. Shakespeare, always hidden behind his work, allows the giant personalities of his plays to act and speak for themselves.

Hamlet’s knowledge has no limits, because he does not love anyone. Lear’s increase in knowledge always augments suffering, because he loves Cordelia and the Fool. Frequently Hamlet plays the part of himself, since he is theatrical to the core. Lear knows nothing of playing; it is alien to his vast nature.

What is authority to Hamlet? You could argue that the dead father assumes that role. Yet Hamlet’s relation to the Warrior-King Hamlet seems equivocal. The ghost of King Hamlet expresses no love for his son, but only for Gertrude, now the wife of the usurper and regicide King Claudius. Though Prince Hamlet says, “He was a man, take him for all in all, / I shall not look upon his like again,” we wonder about that “all in all.” Do we not hear in that the father’s lack of love for the son? Yorick, the King’s jester, was the child Hamlet’s surrogate mother and father, carrying the little boy about on his back: “Here hung those lips that I have kissed I know not how oft.” The Prince has no memories of kissing King Hamlet, and cannot we surmise a sorrow at the heart of his mystery?

King Lear has an enormous need to be loved, by his daughter Cordelia in particular. Shakespeare is nothing if not elliptical and we learn to quest for what has been left out. Nothing is said of Queen Lear. Presumably she is deceased, hardly surprising since Lear is well over eighty years of age. Had she survived, there would have been no place for her in the drama. How horrifying it would have been had she shared Lear’s privations, exposed out on the heath.

As we first encounter him in the play, Lear is very difficult to love. He wants to abdicate and yet retain all his authority. Incapable of distinguishing between the hypocrisy of Goneril and Regan and the loving recalcitrance of Cordelia, he is given to amazingly fierce misunderstandings, and to furious cursings. And yet from the start we can see that he is venerated by everyone humane and decent in the drama. Kent, Gloucester, Edgar, Albany join Cordelia and the Fool in their love for him, while Goneril, Regan, Cornwall, Oswald loathe him. Edmund the Bastard, the brilliant tactician of evil, neither loves nor hates anyone, and is so alien to Lear that they never exchange a single word anywhere in the play, though they are on stage together for crucial scenes at the start and the finish.

There is something uncanny in Lear’s greatness. Shakespeare has combined in the aged King the attributes of fatherhood, monarchy, and divinity.

CHAPTER 2

Meantime We Shall Express Our Darker Purpose

Lear’s drama begins with him still offstage. His loyal followers, the Earl of Kent and the Earl of Gloucester, discuss the forthcoming division of the kingdom, which does not alarm them. King James I would not have been amused and the audience probably shared his reaction. Shakespeare introduces the silent and ominous Edmund, bastard son to Gloucester. Insensitively, Gloucester refers to Edmund as the whoreson. The first word spoken by Edmund is “No” and he sounds icily prophetic by assuring Kent: “Sir, I shall study deserving.” That ironic understatement reverberates with disasters to come:

Gloucester: But I have a son, sir, by order of law, some year elder than this, who yet is no dearer in my account. Though this knave came something saucily to the world before he was sent for, yet was his mother fair, there was good sport at his making, and the whoreson must be acknowledged. Do you know this noble gentleman, Edmund?

Edmund: No, my lord.

Gloucester: [to Edmund] My Lord of Kent. Remember him hereafter as my honourable friend.

Edmund: My services to your lordship.

Kent: I must love you, and sue to know you better.

Edmund: [to Kent] Sir, I shall study deserving.

act 1, scene 1, lines 18–30

The entrance of the great King is marked by his first speech, baleful and desperately confused:

Meantime we shall express our darker purpose.

Give me the map there. Know that we have divided

In three our kingdom; and ’tis our fast intent

To s...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Dedication

- Author’s Note

- 1. Every Inch a King

- 2. Meantime We Shall Express Our Darker Purpose

- 3. Thou, Nature, Art My Goddess

- 4. Now Thou Art an O Without a Figure

- 5. O Let Me Not Be Mad, Not Mad, Sweet Heaven!

- 6. Poor Tom! / That’s Something Yet: Edgar I Nothing Am

- 7. O Heavens! / if Yourselves Are Old, / Make It Your Cause

- 8. This Cold Night Will Turn Us All to Fools and Madmen

- 9. He Childed as I Fathered. / Tom, Away

- 10. He That Will Think to Live Till He Be Old, / Give Me Some Help!

- 11. But That Thy Strange Mutations Make Us Hate Thee, / Life Would Not Yield to Age

- 12. Humanity Must Perforce Prey on Itself, / Like Monsters of the Deep

- 13. O Ruined Piece of Nature, This Great World / Shall So Wear Out to Naught

- 14. Thou Art a Soul in Bliss, But I Am Bound / Upon a Wheel of Fire

- 15. Men Must Endure / Their Going Hence Even as Their Coming Hither. / Ripeness Is All

- 16. The Gods Are Just and of Our Pleasant Vices / Make Instruments to Plague Us

- 17. We That Are Young / Shall Never See So Much, nor Live So Long

- Acknowledgments

- About the Author

- Copyright